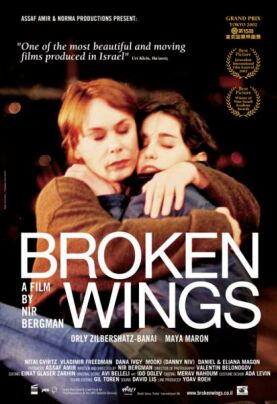

Broken Wings (Knafayim Shvurot)

Broken Wings (Knafayim Shvurot), by the Israeli director Nir Bergman, follows something of a convention for movies about grief by firmly anchoring itself in a particular place. What New York was to last year’s In America and what small-town New England was to In the Bedroom a couple of years ago, Haifa is to Broken Wings. The film begins with a shot of a train passing in front of the down-at-heels Israeli port against a leaden sky. All the way through, just getting around in this grim, ugly city seems an intolerable burden. The ramshackle car that the young but burnt-out looking widow, Dafna Ulman (Orly Silbersatz Banai), depends on to get to her job as a midwife regularly refuses to start, forcing her to seek help pushing it. When Valentin, a new doctor (Vladimir Friedman) at the hospital recently arrived from California, gives her a ride on his motorbike she asks him: “Why did you leave California? Did you kill someone?” Why else, in other words, would anyone come to this G-d-forsaken place?

I guess that making movies about absence must involve a lot of hard work on presence. The oppressive presence of Haifa helps to make the oppressive absence of Dafna’s husband from her life and that of her four children more real to us, though we are only very gradually made aware of his death. And of how it happened. And who feels guilty about it. And why. There is another sort of absence here, and that is the absence of the political turmoil we in America, at least, associate with Israel and the Middle East. My sense of this may be nothing but an artefact of my American perspective, but I can see why Bergman would have wanted to keep politics out of his movie. For all the horrors that Israelis have to live with because of it, the intifada does give a kind of meaning to their lives and deaths. But Dafna’s husband’s death came as the result of an absurd accident. Meaning is another absent party here.

This absence is underscored when her youngest son, Ido (Daniel Magon) — whose method of being absent consists of retreat into a fantasy world where he is the world’s greatest jumper — hits his head on jumping into an empty swimming pool and falls into a coma. Once again, there is plenty of guilt to go around. Neither Dafna nor her two elder children, Maya (Maya Maron) and Yair (Nitai Gaviratz) were looking out for Ido as they would have been doing had they not been reduced to a near-somnambulistic state by grief. It was only because they had also neglected Ido’s little sister, Bahr (Eliana Magon), that the alarm was raised. Thus we are led to a place where a whole family of sleep-walkers — and the sleep motif is stressed throughout the film — have to bring all their depleted energies to bear to try to wake someone up.

Unsurprisingly, they are tempted to think that if their agonized prayers are answered, relief can only come from somewhere else. “Don’t you have something to wake him up?” Dafna asks Dr Valentin. “Some trick you learned in California?”Maya has a quarrel with her mother and runs away to Tel Aviv, where the band she sings in has an audition for a recording contract. The centripetal force exerted on all their lives by that hospital room in Haifa seems at first to be broken. But the song they are recording is the one Maya wrote about her father’s death, and she is ultimately drawn back to her family.

Movies about people trying to cope with a sense of meaninglessness are always a tricky proposition. You risk winding up either with one of those dreary, 1970s-style exercises in nihilism or something merely glib and facile. When Jim Sheridan came to make In America he boldly decided to grasp glib in one hand and facile in the other and dissolve his grief-stricken family’s problems in a sugary confection made up of Disneyland, E.T. and an ice-cream parlor called “Heaven.” As his title suggests, the family’s escape from Ireland to America is definitional, a move from death into life. Not only poor dead Frankie but his — and his family’s — whole country has to be cut loose in order for the family to recover.

The family of Todd Field’s In the Bedroom (2001), now available on video and DVD, consists only of Tom Wilkinson and Sissy Spacek, the surviving parents of an only child murdered by his girlfriend’s estranged husband. They too are nearly destroyed by grief, both individually and as a couple, until the steady rhythms of life in their close-knit community — along with the chance for revenge it affords them — work their calming magic.

Perhaps Broken Wings is more appropriately compared, however, with the best of the recent movies about grief, Nanni Moretti’s The Son’s Room (2001), also now available for home viewing. For both offer no easy escape, either from grief or from the familiar places and people that make it even more intolerable. Yet neither do they leave us with the sense of the meaninglessness of loss. As Maya puts it, who only explains her own crushing burden of guilt near the end of Bergman’s film: “It could be worse, couldn’t it — this s****y life? It really could be worse. And about Dad, too. That could be worse.” It’s not a lot to hang on to, but it’s something real. And without it there is only despair.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.