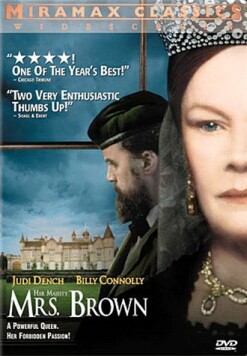

Mrs. Brown

Mrs Brown written by Jeremy Brock, directed by John Madden and

starring Judi Dench as Queen Victoria and Billy Connolly as her servant, John

Brown, is a Masterpiece Theatre costume drama, based fairly faithfully on true

events, which has found its way onto the big screen and manages, in spite of all

expectations, not to look lost there. This is partly owing to the excellent

performances of the two principals, and of Antony Sher as Disraeli, and partly

to the skill of the story-telling and the beauty of the photography. Most of the

latter was shot on location at the royal residences of Osborne House on the Isle

of Wight and Balmoral Castle in Scotland.

The story is of the transformation of the

Queen’s household by the arrival there

in 1864 of Brown, who had been a gillie, or hunting and fishing servant, of her

late husband, Prince Albert, in Scotland. He has come ostensibly to look after

the Queen’s pony, but he swiftly finds

that she requires a much more important service from him, namely the deliverance

of herself and everyone around her from her imprisoning grief over the

Prince’s death. She has kept herself

shut away from the world for three years already at this point with a seemingly

inflexible will, though in fact she is simply paralyzed by the loss of someone

she had come to rely on so much. Brown realizes this and he proceeds to bully

her out of her misery and paralysis by acting as the Prince himself would have

done with her. Soon, Brown is helping her on to her pony by saying

“Move your foot,

woman!” And, to the horror of her

largely sycophantic advisers and attendants, she moves it.

To the gentlemen of her household, Brown is a mere servant, and a Scotsman

to boot, but it is his manly willingness to take her in hand which is all that

matters to the queen. To her mind he in effect assumes a

husband’s place. Hence the

film’s title, taken from

Disraeli’s sardonic description of Her

Majesty behind her back—though the film is mercifully reticent about the

possibility of any sexual relationship between them. Naturally, he makes enemies

of Sir Henry Ponsonby (Geoffrey Palmer), who had had the management of the

Queen’s affairs before he came on the

scene, and of the Prince of Wales (David Westhead), whose access to his mother

he limits as strictly as anyone

else’s. Disraeli, however, is a more

subtle figure and realizes that

Brown’s disingenuousness and genuine

concern for the Queen’s well-being can

be of use to him, even though, oddly enough, he finds himself as much on the

side of the Queen’s well-being as

Brown.

The best and most memorable scene comes when Brown drives the Queen to the

rather distant house of Bob Grant, a former fellow-gamekeeper on the royal

estates, where she is treated (as much as possible) as an ordinary person, even

helping to set the table for dinner. This is obviously the first time she has

ever performed such a simple domestic task, and at one point Brown has to give

her a signal about where to put the spoons. They come back later than expected

and rather flushed from the fresh air and perhaps the drink. Sir Henry Ponsonby

and Dr. Jenner are first shocked that she has come back late, then even more

shocked that she must be

“drunk”—until

finally it dawns on both that the

Queen’s flush might be owing to

something else.

“Don’t

even think about it,” says one to the

other.

This is the nearest the film gets to displaying any prurient interest in the

story, which seems to me almost a miracle of restraint in this day and age.

Instead it carefully interweaves the complex personal and emotional relationship

between the two with the considerations of political and state affairs with

which it is inevitably bound up. Perhaps the most revealing moment comes when

Brown offers to resign her service, and the Queen is forced to beg him to stay.

“Promise me you

won’t let them send me

back,” she says, referring (I suppose)

to the obsequious management of her grief Sir Henry and others used to control

her before Brown came and bullied her into living again. Perhaps the

estrangement which ensues upon Brown’s

risking his credit with her by persuading her back into public life in 1868 does

not emerge with quite sufficient sharpness, but the general outline is clear

enough, and the ending touches just the right note.

A film well worth seeing.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.