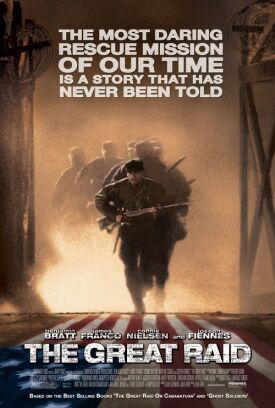

Great Raid, The

No, this won’t do, said I to myself. An American officer in John Dahl’s new movie, The Great Raid had been given the tremendously dangerous and daring mission of rescuing several hundred other Americans from a hellish Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. Now he was rejecting a particular tactical suggestion by saying “I can’t guarantee the safety of the prisoners.” Guarantee their safety? It would have been far more plausible for him to speak of guaranteeing their murder — as the film itself clearly shows in a horrific scene of another group of American prisoners whom the Japanese had herded into a bomb shelter and set on fire. The phrase was clearly just a momentary anachronism, a lapse into the vocabulary of our own risk-averse era — as if it were possible ever to guarantee anyone’s safety — and out of the characteristic idioms of 1945 when the real life events on which the movie is based took place. It was like hearing World War II era people talking of “hooking up” — which they also do here.

But sloppiness about getting the dialogue right often betokens other problems with a movie, and that proves to be the case here. There is even something not quite right about Benjamin Bratt’s Colonel Mucci, the leader of the rescue mission. He has the ruggedly handsome look of an ideal American Ranger and all the accessories — the pipe, the pencil-thin moustache (which he has to shave lest he advertise himself as an officer), the non-regulation cap of the irregular jungle fighter — but they are too firmly in place. He is, in short, too perfect. He looks not like a Colonel of Rangers but like a male model dressed up as one. He lacks the untidiness of authenticity. So does the raid itself. According to the publicity, the film is an account of “the greatest rescue mission ever attempted,” but even if we allow for Hollywood hyperbole, the film doesn’t deliver. The greatest rescue mission ever attempted looks just a bit too much like a walk in the park. Nothing goes seriously wrong. Nobody gets very dirty or bloody. Only a couple of the good guys — though naturally all of the Japanese — are killed.

It’s possible that what looks like a prettying up of the nastiness of war was deliberate, and at times The Great Raid seems to aspire to the unworldliness of epic poetry, where the heroes, just because they are portrayed as being larger than life, are allowed to stand around making noble and inspiring speeches. “How you acquit yourselves over the next 48 hours will determine how you are regarded for the rest of your lives,” says the Colonel to his men in an absolutely classic appeal to the warrior’s lust for fame and renown.

“I don’t suppose many of us are in this for the glory,” says someone to him, half in reproach.

“I’m not talking about publicity,” explains the Colonel, “but something you carry inside you.” That’s why “nothing in our lives will ever be as important.”

This is an admirable dissertation on honor — which, of course, is not mentioned as such — but to my ear it strikes a false note. That kind of epic sentiment, even reduced to a sentence of colloquial speech, is almost always a mistake in so realistic a medium as the movies. Ronald F. Maxwell tried it in Gettysburg (1993) and then again in Gods and Generals (2003) but neither time was he able to produce anything much more than a laughably wooden-looking series of tableaux vivants. I felt sorry for Maxwell, as I feel sorry for Dahl, because the impulse behind their artificial style of film-making is a laudable one, namely an exaggerated respect for the heroism of real life soldiers to whom all respect is due. But what is perfectly acceptable in history — or in epic poetry — is much harder to make work on the big screen. Maybe Abel Gance’s Napoléon (1927) managed it, but it helped a lot that that was conceived as a silent film.

There are other problems with The Great Raid. It aspires not only to epic stature but also to epic sweep, though at 132 minutes it is both too long and not long enough to achieve the epic’s leisureliness and sense of familiarity with its characters. Once the rescue operation starts, the action is rather hard to follow, partly because of the usual fog of movie-war but also because the characters are too undifferentiated. Moreover, the story of the sundered lovers, the prisoners’ leader Major Gibson (Joseph Fiennes) and Margaret Utinsky (Connie Nielsen), the widow of Gibson’s former commanding officer, seems surplus to requirements. Margaret herself is a leader of the anti-Japanese underground in Manila, and the idea of including her exploits there is partly to add a third, intertwined narrative to that of the American prisoners’ attempt to forestall their execution by the Japanese and that of the Ranger company trying to rescue them But it’s all too much. Her part in The Great Raid itself is obscure and unnecessary and her scenes badly slow down the pace of the dramatic rescue.

Of course, Margaret also symbolizes the distant and perhaps unattainable prospect of civilian life and domestic happiness to a man who would otherwise have forgotten what these things were like. But here too the Margaret-in-Manila scenes come across rather as a distraction than as a contribution to the film’s broader themes. We hardly need to be told that the prisoners would much rather have been back in civilian life and close to their loved ones.

I hope I’m not being too hard on the movie. It’s one of those that it pains me not to like. For I approve of its point of view and would like to be able to approve of its methods. I strongly believe in the good intentions behind its celebration of an act of heroism that should not be forgotten. But with the best will in the world, I just didn’t find it a particularly compelling two-hours-plus at the movies.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.