Feeling Nothing

From The American SpectatorWhen I was in London recently, I noticed that one of the city’s chief tourist attractions, Madame Tussaud’s waxworks museum, has got a new advertising campaign. The posters, which are to be found in London Underground stations and elsewhere, are rather wordy and worryingly short on illustration for an institution whose survival must depend to some considerable extent on the patronage of the semi-literate. But then photographs of waxworks could presumably only accentuate their lack of resemblance to their originals and so drive away such custom as might otherwise be lured in by the promise of the allegedly witty messages in a written form of pop-speak. These messages take the form of a series of exhortations to the libidinous of both sexes to “Kick start your dad’s midlife crisis by letting him watch Britney Spears pole-dance” or “Fondle Brad Pitt’s bottom” or, with a cavalier disregard of the Italian singular, “Get closer to Angelina Jolie’s cleavage than a paparazzi’s zoom lens.”

There is, of course, nothing new or surprising about the public display of such cheerful vulgarity in the promotion of the institutions of the celebrity culture, either in Britain or the United States. But what, from an historical perspective anyway, is surprising is how little comment this kind of thing excites from moralists who, in even the most corrupt eras in the past, have never been slow to condemn the coarseness, vulgarity or wickedness of their time. Perhaps it is the fear of being thought humorless or prudish which makes the latter-day Juvenal hold his tongue. It is one of the principal legacies of the therapeutic revolution during the century just past to have made even those who might otherwise have been disposed to moralism ashamed of their own moral principles, or at least of the urge, hitherto thought indispensable from such principles, to “impose” them (as the saying goes) on others. Horror at the idea of being “judgmental” seems to have trumped even disgust at the idea of immodesty and lasciviousness as public and obtrusive as that of the long-dead Madame Tussaud.

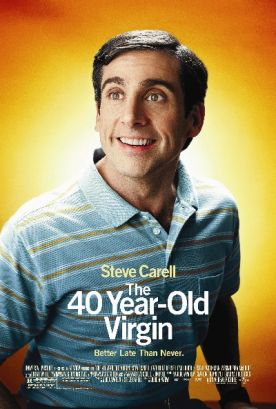

Another advert spotted on London Public Transport was for the American film, The 40-Year Old Virgin. Once again, the authors seemed to think so highly of their own wit as to be able to do without any sort of illustration from the film and confined themselves to the written word, which ran as follows: “It’s time for him to get off his bike and start riding.” To be fair, the movie, which is directed by Judd Apatow from a screenplay he co-wrote with its star, Steve Carell, is not quite so bad as this makes it sound. Though devoted to the proposition that coitus is a form of mental and moral hygiene while celibacy amounts to arrested socialization at best, and actual illness at worst, it ends with a wedding and, if not the de-flowering, at least the de-stemming of Mr Carell’s eponymous virgin only on his wedding night. This is after he has assured his new bride, a youthful grandmother played by Catherine Keener, that he formerly “thought there was something wrong” with himself for remaining celibate for so long, but that “now I realize it was just because I was waiting for you.”

Actually that’s not quite the end. Following a bedroom scene between Mr Carell and Miss Keener which is slightly more discreet than most of the film, it ends with them and the rest of the cast singing “This is the dawning of the Age of Aquarius” from the 1960s hippie musical Hair. Now what, you may wonder, is that doing there? In a movie which is devoted to the raunchiest sort of sex jokes — including one in which the only thing funnier than an episode of drunken driving is the spectacle of the drunken (female) driver throwing up in the face of the 40-year-old virgin — it seems almost as out of place as the romantic pay-off to the relationship between Mr Carell and Miss Keener. But I think this curious coda must have something to do with the inability of those who celebrate sex-play for both men and women — or “hoes”, “hood rats” and “drunk bitches” as they are also known here — as a form of fitness exercise to imagine any sort of sexual idealism without a bit of New Agey free love as a part of it. Too bad that in the context that can hardly fail to cancel out the respect it otherwise wishes to show for marriage. Perhaps Messrs Apatow and Carell were afraid of being accused of what they call “putting p***y on a pedastal.”

The 40-Year Old Virgin

shows us that in an age of political correctness celibacy is, along with religion, right-wing political views and stupidity, one of the few things it is still OK to satirize and ridicule, and in mining this new and rich comic seam, it has become one of the two big comedy hits of the summer, the other being The Wedding Crashers. There too, the built-in cultural assumptions would once have seemed bizarre in the extreme, but excited no commentary at all that I was aware of in the year of Our Lord 2005. Unscrupulous males who are willing to use the suggestive but now obviously outmoded rituals of matrimony in order to cozen young women into sacrificing their maiden treasures and then to abandon them are all but universally understood to be engaging in nothing more than good clean fun. So much so, indeed, that the movie ends — watch out for the spoiler here — with the suggestion that even when the seducers have found romance, they will continue their wedding games with the connivance and possibly the participation of their new-found lady-loves.

Well, of course we mustn’t read too much into what some of my more disapproving readers continually assure me is mere “entertainment.” But is corruption less or more corrupt if we are to suppose that the debauchery of what the Church once taught could only be, in its right use, a spiritual and fleshly gift consecrated to God is only a matter for amusement? In The Wedding Crashers one of the two jolly seducers, the one played by Vince Vaughn, is ostensibly shocked to learn that his latest of many partners is, or rather was when he enjoyed her, a virgin. But this is only because he is afraid that the fact will make her a “clinger” — which is to say, more difficult to abandon now that he has had his way with her. Soon, however, he is relieved to learn that she has deceived him with reports of her virginity — not because she wished him to think her a virgin for any claim it might create on him but as just a bit of fun itself. A joke. And what else could you call the idea that any normal person could have reached the age of consent, or a few years or weeks beyond it with virginity intact? In short, it is the same joke as the (only) joke in The 40-year Old Virgin.

A not very enthusiastic recommendation as the Movie of the Month, then, to Jim Jarmusch’s Broken Flowers. As a commentary on the culture of hygienic, commitmentless sex, it doesn’t have much to say except by omission. Bill Murray plays an aging playboy who receives an anonymous letter informing him that he has an 18 year-old son by one of his many ex-girlfriends. Prompted to it by a friend who makes all the travel arrangements in Jarmusch-generic America, he goes off in search of the mother before the son, possibly, can find him. As I say, the meaning of the pilgrimage can only be a negative one, and what is left out is any sense either or regret and remorse on the one hand or of defiance and denial on the other to tell us what we are to make of the morality and the meaning, if any, of a Don Juan in the Age of Aquarius.

Bill Murray’s Don Johnston, therefore, doesn’t cut the dashing figure of his 18th century. namesake. In treating of women as temporary means to his own gratification and sex as nothing more than physical sensation, he shows that he is just a sort of Everyman. Only for a moment, when he meets a boy whom he believes to be the missing son, is there a tiny hint of the possibility of a meaning to the physical act of love which might be, however distant, an echo of what the Christian and other religions used to thunder that it was and had to be. But to Jarmusch that thought, qua thought, is almost literally unthinkable, as it is of course also for the film-makers who brought us The Wedding Crashers and The 40-Year Old Virgin. At least he, unlike them, has the grace to shape it as a feeling — and as a feeling of sadness at something lost, perhaps forever.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.