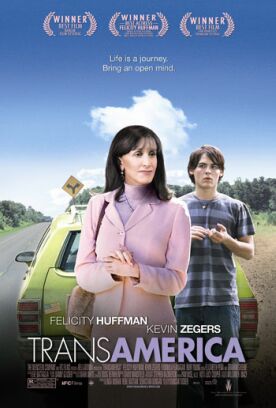

Transamerica

Americans have always been inclined to belief in a divine right of self-reinvention. The land of immigrants has remained for those immigrants’ children and grandchildren the land of second chances. When this bedrock faith of the American people is put together with advances in medicine, you get the new and strange romance of “gender reassignment.” One such tale is the subject of Duncan Tucker’s Transamerica. The punning title suggests that Mr Tucker sees this connection between the aspirations of transsexuals and the American dream, but it also refers to the cross country journey of his two heroes, the pre-operative transsexual Sabrina, “Bree,” Osbourne (Felicity Huffman) and his/her teenage son, Toby (Kevin Zegers). Although the movie is conceptually confused and content to rely on Hollywood’s — and the popular culture’s — easy assumption that feelings trump all moral considerations, the performances of these two actors are almost enough by themselves to make the movie worth seeing. Reduced to the level of mere emotion, it is a memorable study of pain and shame and hope.

The trouble is that reducing it to that level is a highly artificial act — more artificial even than Bree’s sex. It and the demands the film makes upon its audience’s compassion silence any urges to further moral reflection. This is the more to be regretted because the presence of Toby vastly increases the potential for such reflection. As a college student and still going under his birth name of Stanley Schupak, Bree fathered Toby without realizing it. He says it was his one and only sexual encounter as a man with a woman. Now, seventeen years later and on the very point of his “reassignment” surgery, he learns of Toby’s existence, and his therapist, Margaret (Elizabeth Peña), insists that he fly from Los Angeles to New York to meet the boy. “Bree,” she says, “this is a part of your body that cannot be discarded.”

It’s a very curious way to refer to the connection between parent and child, you might think, but thematically it points us towards Bree’s dislike of the whole idea of anything so unlike her current self as fatherhood. For her, artificial femininity almost seems like an excuse for her much more natural prissiness. When a doctor asks her how she feels about her penis, Bree replies that “it disgusts me,” and that’s pretty much how she feels about that other body part, Toby, as well. There are other reasons for this, however. Toby, a runaway scraping a living as a male prostitute in New York, comes to Bree’s attention when he is arrested for shoplifting. A thief, a prostitute, a drug-user and seller, Toby offers the more “judgmental” sort of viewers, too, plenty to inspire disgust. But the movie sets Bree the task of overcoming this disgust as the price of her surgery — and therefore also the price of no longer having to overcome her disgust with her masculine body.

Put like that, it does seem a little weird, doesn’t it? Feelings are sovereign here except when they are inspired by moral conviction. The film hardly dares to touch on the subject of any reformation of Toby’s manners and morals. Though it ends with what I take to be the upbeat note of mom/dad’s telling the boy to get his feet off the coffee table, his new career as an actor in gay pornography elicits no slightest note of censure. Of course all is excused when we learn that Toby’s mother committed suicide and his stepfather physically and sexually abused him, forcing him to run away. Victimhood for him as for Bree — who is of course the victim of what she takes to be nature’s mistake in making her a man — dissolves all other moral considerations in a warm bath of pity. Though any question of Toby’s prospective moral transformation is treated as rather indelicate and certainly not to be insisted upon, his father’s prospective transformation from man to woman admits of no question at all to anyone but his/her splendidly awful mother (Fionnula Flanagan).

The best scenes in the film are those in which Bree arrives on her parents’ doorstep after many years’ of estrangement and introduces Toby to them as their grandson — though her shame is still such that she cannot bear to inform Toby that they are his grandparents. This leads to some comic misunderstandings to which the great Burt Young as Bree’s father and Carrie Preston as her younger sister make creditable contributions. Generally speaking, fatherhood gets a bad rap in this movie as it so often does in Hollywood these days. It disgusts Bree, tempts Toby’s stepfather into evil and depravity and seems to embarrass Bree’s own father. But then the portrayal of family life as a chamber of patriarchal Gothic horrors is really a natural corollary of Hollywood’s firm and often-repeated belief in the invented family as a substitute for the consanguineous kind. It’s a small step from here, perhaps, to the re-invention of God’s fatherhood, in which the film also dabbles.

Before she reveals to Toby either that she is still a biological man or that she is his father, Bree pretends to have bailed him out as a representative of “The Church of the Potential Father.” Thereafter, Bree-as-Jesus-freak becomes one of the movie’s running jokes, and it ends with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band singing “I find Jesus on the darkest night” Needless to say, this is a Jesus without judgment, a Jesus who is all mercy and compassion and no wrath or righteousness of the sort that was once thought by the church He founded to be expected of Him when all our accounts are rendered. Wouldn’t it be nice to think that it might be so, and that the benediction of the Almighty might be expected upon Bree’s and Toby’s unconventional life choices as upon our own? But I myself don’t see any other reason for believing in such an indulgent, undemanding god beyond Hollywood’s style of wishful thinking.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.