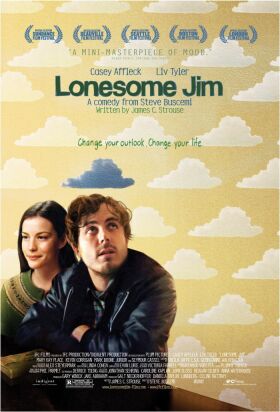

Lonesome Jim

Directed by the actor, Steve Buscemi, from an autobiographical first script by James C. Strouse, Lonesome Jim takes on a big subject and does a creditable job with it. Like its hero, it’s not quite sure where it is going, but, unlike him, it has a lot of fun getting there. Jim (Casey Affleck) returns at age 27 to his home town of Cromwell, Indiana, having failed to make it as a writer in New York. He seems even to have failed at dog walking, which is what he did to earn money while trying to write. His father, Don (Seymour Cassell), is obviously less than overjoyed at the prospect of a grown son moving back in with them, not least because his older son, Tim (Kevin Corrigan) has already done the same. He orders Jim to go to work in the family’s factory making ladders.

But his wife and the boys’ mother, Sally (Mary Kay Place), welcomes Jim without conditions and is completely uncomplicated in her happiness at having her sons living at home with her. She ignores the musk of failure that clings to both of them, and, when Jim the prodigal returns, fusses over him excessively. She even barges in on him when he is in the bathtub and calls him her boy. “I’m not a boy, mom,” says Jim, wearily as he shields his private parts.

“Yes you are. You’re my boy. My pretty boy.”

At first it looks as if this smothering mother is connected to Jim’s depression, which at times renders him almost catatonic. The indifference, bordering on hostility, with which he greets her professions of love and affection somehow seems to make sense as the family sit around the heavily-laden breakfast table and listen to “Love Can Make You Happy” by Mercy on the easy-listening station. The impression is furthered by the suicidal mood of brother Tim. “What did we do to make you kids so unhappy?” mom asks Jim.

“I don’t know,” he thoughtlessly replies. “Maybe some people just shouldn’t be parents.”

Tim is an even bigger failure than Jim is. Jim couldn’t make it in New York; Tim couldn’t even make it in Cromwell.”I think about ending it all as it is,” says the younger to the older brother. “I can’t even imagine what it must be like to have your life” — that is, divorced with two daughters and a hostile ex-wife, rejected by the Cromwell police force, living with his parents and working for minimum wage. “I’m a f***-up,” he adds, “but you’re a goddamn tragedy.” Tim promptly goes out and wraps his car around a tree — not his first “accident,” though the only thing accidental about it, he later maintains, is that he lives, albeit with two broken legs.

But, refreshingly, mom turns out not to be the problem. On the contrary, her love for her “boys” is movingly direct and genuine, and we gradually come to value it, as does Jim himself, as the touchstone of goodness and decency in a world darkened by sadness. It helps, too, that Jim has growing feelings for a divorced nurse, Anika (Liv Tyler), and her young son, Ben (Jack Rovello). Anika is as upbeat as Sally is. She likes to help people, she says, when Jim gets jealous to find her visiting bedridden Tim. Meanwhile, as far as Tim is concerned, the fact that Anika is sleeping with his brother must mean that “she has no standards. I bet she’d do it with me, too.”

That kind of nastiness presumably arises out of his self-loathing, and it is echoed in Jim’s Uncle Stacy (Mark Boone Junior), who likes people to call him “Evil” and who also works at the ladder factory. Fat, hirsute and utterly unprincipled, Uncle Evil lives up to his name, dealing drugs out of his trailer and blackmailing Jim when Sally gets sent to jail for his misdeeds.

And yet the movie is also often laugh-out-loud funny. What I liked about it is its exposure of the absurdity of despair, evident in the insane competition between the two brothers as to who is the more miserable. “I sort of came back to have a nervous breakdown,” Jim confesses to Anika, and then adds under his breath: “Bastard beat me to it.” We see that the problem here is that the despairing take themselves so seriously, mistaking their gloomy mental world for the whole world and their feelings for the whole world of feelings. And the only thing more absurd than someone’s taking himself too seriously is someone who doesn’t have a clue that that is what he is doing.

Tim falls into the latter category, but Jim gradually emerges from his room decorated with photos of the suicidal writers — Poe, Virginia Woolf, Hemingway, William Burroughs — who are his heroes into a degree of self-awareness and self-detachment, which are remedies for both despair and absurdity. The only thing I didn’t like about Lonesome Jim is that Tim’s assessment of Anika as lacking standards is uncomfortably close to the truth. She likes to show off her tolerance for hard liquor and jumps into bed with Jim within moments of meeting him. Ben’s father is clearly a bum and so is Jim for most of the movie. Why does she put up with him? I suspect that, having gone way out on a limb to give us a portrait of goodness in Jim’s mother, Mr Strouse decided he’d better draw back from such saintly excess and humanize Jim’s girlfriend a bit — and that he didn’t know any other way to do it. But in the scheme of things this is a small flaw and doesn’t prevent the movie from being well worth seeing.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.