American Dreamer

From The American, November/December, 2006A hundred years ago last July, 22-year-old Chester Gillette took his 20-year-old girlfriend, Grace Brown, for a boat trip on Big Moose Lake in the Adirondacks. Grace was drowned and, when it was learned that she had been pregnant, and that Gillette had been seeing a much wealthier girl on the sly, he was charged with murder, tried, convicted and executed. Nearly 20 years later, his story became the basis for Theodore Dreiser’s novel, An American Tragedy — about which, in retrospect, the most interesting thing was the title. Certainly, the death of Grace, whom Dreiser re-named Roberta Alden, was a tragedy in the journalistic sense of the term, but Dreiser made it clear that he was aiming at something more like classical tragedy, which described the fall of a great man, and that the (ironically) great man in this case was Clyde Griffiths, the name he gave to the Gillette character. Moreover, the Americanness of his tragedy was meant to account both for Griffiths’s greatness and for the putatively “tragic” nature of his crime. America was implicated in the murder; America — and the hope that it represented to so many — was what made it a tragedy.

Nor was Dreiser’s odd use of the epithet “American” merely idiosyncratic. Clearly, it has resonated with generations of readers. The anniversary of Grace Brown’s drowning last summer was marked by a kind of celebratory folk festival, including the unveiling of a plaque at Big Moose Lake commemorating the fatal boat ride, re-enactments of the murder and the trial and readings of Grace’s letters to the faithless Chester as well as a three-day scholarly conference. All these things suggest the iconic status of Dreiser’s hero, whose arrival on the scene coincided with and exemplified a fundamental change in the idea of heroism itself. The traditional hero, master of people and events, had taken such a beating from the mythologization of the random slaughter of the trenches in the First World War that even today he has not yet managed to pick himself up off the canvas. The hero’s successor, the anti-hero, was not the master but the victim of his world. Like Chester Gillette or Clyde Griffiths, he was portrayed as flailing helplessly in the grip of forces he is powerless to control — forces that were variously identified as God, fate, “the [capitalist] system” or, in Dreiser’s case, America itself which, with its promises of wealth and the freedom wealth brings, could be said to have lured Clyde Griffiths to his destruction.

Jim Cullen, author of The American Dream: A Short History of an Idea That Shaped a Nation, claims that the expression “the American Dream” made its first literary appearance in 1931 in The Epic of America by James Truslow Adams, but the more usual meaning of the expression today as an ever-receding hope that somebody has been unfairly excluded from was pioneered by Dreiser, whose title implied that it was somehow, even if indirectly, the fault of America and that lustrous immigrant’s dream that America held out to the world that Chester had murdered Grace or Clyde had murdered Roberta. In other words, even before the American Dream had been formulated as a concept — though not, of course, before there were lots of American and would-be American dreamers — its negative meaning as a cruel delusion was ready and waiting for it.

There was a somewhat similar subtext to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby which came out in the same year (1925) as Dreiser’s book and which Fitzgerald later wished he had titled “Under the Red, White, and Blue.” As in An American Tragedy, the fatal attraction of wealth and social advancement for Americans, particularly those who were or wanted to be upwardly socially mobile, is conceived of in tragic terms that have since made the story iconic. Both Clyde Griffiths and Jay Gatsby — his titular “Great” is ironic and marks him from the start as an anti-hero — are meant to suggest an American Prometheus, destroyed by the envious gods of money and class they aspired to join, an Icarus who flew too near to the sun and was dashed to earth for his presumption. Already, before the term was even coined, the American Dream also carried with it overtones of tragedy.

Though Gatsby was not a success in Fitzgerald’s lifetime, it is now regarded by many as the greatest of American novels. That it is one of the most assigned books for reading in high school and college courses in American literature can be gauged by the number of study notes devoted to it, both in print and on line. It has been adapted for stage and screen and turned into an opera by John Harbison. Iconic, ironic Gatsby has become the prototypical American, and Americans have become as proud of him as he was of his newly-acquired wealth. But this admiration is necessarily patronizing: we love Gatsby for his illusions but also because we do not share them. Or at least we like to think of ourselves as disillusioned. We need him because he stands for that essential American “innocence” which is forever being “lost” — and, without ever being found, lost again. He is like “the American Dream” itself which, in its unironic form, is mainly confined to advertising slogans — The Wall Street Journal bills itself as “the daily diary of the American Dream” — but derives its real emotional force from being a negativity, an absence that we feel entitled as Americans to resent.

That is the reason for the booming academic industry in Gatsby studies as well as such casual manifestations of the idea’s evocative power as the Seattle rock band that calls itself “Gatsby’s American Dream.” Gatsby’s greatness lies in his ability to turn the bitterness of those who see the American Dream as a false promise into pathos, a process that has by now become a journalistic cliché. The movie Little Miss Sunshine, writes Manohla Dargis in The New York Times, is “a tale about genuine faith and manufactured glory that unwinds in the American Southwest, but more rightly takes place at the terminus of the American dream, where families are one bad break away from bankruptcy.” Foreigners like Jim Fish of the BBC are particularly fond of this negative version of the dream. Comparing race relations in Britain and France with the USA recently, he said: “And in the most renowned melting pot society of all, the United States, Hurricane Katrina exposed the grim reality that far too many black people remain at the bottom of the pile, too often ignored and cut off from the American Dream.”

Ironically, for such people the Dream is not a dream at all but an absent reality. Their approach to it is like that of the New York Times critic Stephen Holden who, in a recent profile of the singer Tony Bennett, characterized President Bush’s America as “an arrogant empire drunk on power and angry at the failure of the American dream to bring utopia.” Utopia? Wasn’t that the Soviet dream? But Utopia — “no place” in Greek — was also not there in America, and its not-thereness was remarked upon much more often. From the beginning the American Dream seems to have shared with the Soviet one — which, by the way, came along at about the same time — that utopian quality. The promise of utopia was hard to compete with if you were in the promising business yourself, as America was. Indeed, the American dream as first formulated must have owed something to the felt need to offer something like the promise of the Red Dawn, only for Americans and achievable through a more democratic and capitalist route — and perhaps, though not with perfect consistency, with the stipulation that it was not to be understood as pointing us towards an impossible state of earthly perfection.

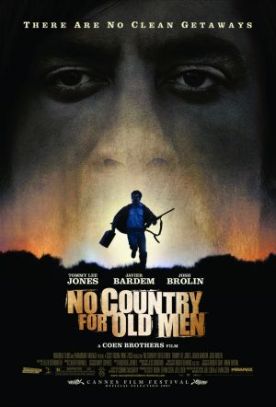

In other words, Mr Holden’s assumption of a utopian dimension of the American Dream must also have been there, even if only implicitly, from the beginning. Certainly, that dimension has been very helpful in feeding the cultural and political appetite for the romance of disillusion, which took on such importance between the wars. If you make the impossible your goal, you guarantee a future of picturesque disappointment. This, it could be said, was the point of what has since come to be called the films noirs of the 1940s and 1950s. One such was an adaptation of Dreiser’s American Tragedy called A Place in the Sun (1951). Hollywood had to make a few changes in Dreiser’s story. Montgomery Clift’s George Eastman — yet another name given to the man who started out as Chester Gillette — can’t bring himself to kill Grace/Roberta, now re-named Alice Tripp, even though, as she is played by a whiny and emotionally blackmailing Shelley Winters, Alice must have inspired a lot of movie-goers to wish he would kill her.

Instead, her death is depicted as an accident, but Eastman accepts his fate as deserved because he had intended to kill her. It is not too much to say that he comes off as a saintly figure, consoled in his last hours by a radiant Elizabeth Taylor in the role of the rich girl whose love is undimmed by his actions and whose moral as well as material superiority to her dead rival does more even than the promise of America to make his tragedy understandable. This was another way to skin the cat, but the point was the same. The humble fellow of no birth, wealth or distinction who only wanted to get ahead in the world but who was struck down by the gods or the fates or the powers that be for his ambition took on the stature and the nobility of the ancient heroes who were not afraid to stand against impossible odds, or to take on the tyrants of heaven or earth who demanded their subservience. This became a standard scenario of the film noir, as in Double Indemnity (1944) or The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946), except that in those films there was less squeamishness than in A Place in the Sun about making the victim-hero into an unabashed murderer — and a thief to boot.

The heroes of these films were not, like Montgomery Clift, bucking for sainthood. Rather, they were just little guys who were trying to score big for once in their lives. The Hays Code, which decreed that criminals could not be depicted in the movies as profiting from their crimes, or getting away with them unpunished, helped to create this scenario — one of many examples, and perhaps the chief of them, of how what would now be called “censorship” actually made the movies better. For there was an undeniable emotional power in the American tragedies of men like Chester Gillette, Clyde Griffiths and George Eastman, men who dared to look for a place for themselves above the miserable station in life that they were born to but who were crushed for their presumption with such inevitability that the malign powers at work to frustrate them could only have suggested to the largely left-wing screenwriters of the era the force that they would have called “capitalism.” Like “America” as imagined by Dreiser and Fitzgerald, this Marxist concept could be conceived of in homologous terms as God or fate or the state or, more vaguely, “the powers that be,” but in whatever guise it appeared it shared with “capitalism,” as understood by the left, the qualites of cruelty and indifference to human aspiration.

Moreover, the political motivations of the screenwriters of the noir era were in tune with the natural tendency to disappointment resulting from the nature of human expectation. As Robert Samuelson notices, “Americans’ very optimism breeds stress and insecurity, because it invites disappointment. For proof, look at the monthly survey of consumer confidence done at the University of Michigan. One question is: Are you and your family ‘better off or worse off financially than you were a year ago?’ Despite steadily rising living standards — measured by new gadgets, larger homes, better cars — it’s rare for more than 50 percent of Americans ever to say ‘yes’.” In other words, hope naturally tends to recede because we naturally want more. This is still as true as ever. The demographer William H. Frey was recently quoted in the Washington Post as saying that the dynamic of recent population shifts in America arises out of people who are still “chasing the American dream” — except that the Dream has changed. “It used to be a home with a Chevy and a television. Now it is a McMansion, an SUV and a satellite dish.”

The banality and, in artistic terms, vulgarity of such success compares interestingly with the nobility of those old, politically-inspired failures. And if McCarthyism never quite succeeded in purging Hollywood of its communistic tendencies, the demise of the Hays Code in the 1960s meant that the external constraint on movie-makers to make their American dreamers tragic figures also disappeared. The result has been, particularly in the last ten or fifteen years, a spate of movies that we might call prison fantasies — that is, instead of his hope of one big score’s leading to the destruction of the hero, now the hope comes true, the score comes off, and he escapes to some sun-drenched tropical paradise to enjoy the fruits of his ill-gotten gains. You only have to compare the original, Rat-Pack version of Ocean’s Eleven (1960) with the re-make of 2001. In the original, a criminal conspiracy to rob several Las Vegas casinos — no one was going to shed any tears over those losses — succeeds brilliantly, only for the money to be accidentally incinerated. Frank and Dino and Sammy and the rest emerge philosophically into the bright sunlight just the same as they were before. At the end of the re-make the crooks, led by George Clooney in the Sinatra role, get away with the clearly fantastical sum of $160 million — though later, in order to set up the sequel (Ocean’s Twelve) three years on, they had to steal that amount again somewhere else in order to pay back the original owner.

That the American Dream has now become the American Fantasy is also suggested by its most recent political use. At about the same time that the Dreiserians were celebrating at Moose Lake, the Democratic Leadership Council was launching something called the “American Dream Initiative.” Developed by Senators Hillary Rodham Clinton and Tom Carper and Governor Tom Vilsack, it promised on behalf of the Democrats to “offer a new opportunity agenda that secures the pillars of the American Dream.” The initiative claims to be necessary because, “over the last five years we’ve taken a different direction, one that offered the greatest help to those with the most wealth” — that is, as it takes no skill in reading between the lines to realize, in the form of the Republican tax breaks for those who have already realized the American Dream. Here are some of the specifics of the DLC’s American Dream Initiative:

- Every American should have the opportunity and responsibility to go to college and earn a degree, and to get the lifelong training they need.

- Every worker should have the opportunity and responsibility to save for a secure retirement.

- Every business should have the opportunity to grow and prosper in the strongest private economy on Earth, and the responsibility to equip workers with the same tools of success as management.

- Every individual should have the opportunity and responsibility to start building wealth from day one, and the security and community that come from owning a home.

- Every family should have the opportunity to afford health insurance for their children, and the responsibility to obtain it.

These are a good illustration of the way in which the art of political rhetoric has in recent years ceased to be the art of saying something and instead become the art of not saying something. Looked at critically, these “pillars” of the American Dream are nonsense. All of these “opportunities” already exist, and pairing them with “responsibility” in each case not only raises unanswered questions about the methods of coercion to be employed to make sure that people live up to their “responsibilities” but actually diminishes or abolishes the opportunities.

If, for example, it is the “responsibility” of every American to go to college and earn a degree, in what sense can this degree be said to be “earned” at all? It becomes essentially an entitlement and is correspondingly devalued — which is exactly what we already see happening to the undergraduate degree in America as more and more Americans think it necessary to have one. And to have the “opportunity to afford” something, whether it is health insurance or a Rolls Royce, is not an opportunity at all. It is either a straightforward entitlement or it is meaningless. But such juggling with words seems to reflect the same thinking engaged in by Mrs Clinton’s husband, the former president, when he paid tribute to the late Ann Richards by saying: “She really believed that we could make a world in which everyone was a winner.” The context suggested that he meant this as a compliment, but of course if everyone is a winner then no one is a winner. For there to be winners there must also be losers. What he, if not Governor Richards, envisaged is a world in which winning and losing have ceased to exist and everybody has what he needs and wants without aspiring to anything higher.

In short: Utopia. No place. The remarkable thing is that Bill Clinton himself was and is such a striver, such a winner, that you might almost think his success had made him feel guilty. During the last year of the Clinton presidency, David Ignatius wrote in the Washington Post that “more than any of our presidents, Bill Clinton is Jay Gatsby,” partly because “he’s still becoming, still aspiring, still seeking validation for what he’s done and who he is.” But Gatsby is also a memento mori, a reminder that, in the end, even winners become losers. The utopian tendency that seeks to make us forget this, that approaches the happiest outcomes for education, retirement etc. as a sort of phantom right has the same political purposes that Dreiser had in the proto-American dream that he called An American Tragedy. Once again, failure is regarded as a reproach to aspiration rather than a spur to it and a prelude to achievement. Once again, anything less than perfection is seen as redounding to the discredit of those in power rather than an inevitable concomitant of the human condition. Artistically speaking, the idea of the American Dream was turned into a fantasy even as the thing itself became so routine that it has come to be seen as a right. And now, not coincidentally, American politics seems well on the way to becoming just a fantastical assertion of rights to happiness and success on behalf of everybody. Some would call that a tragedy.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.