Memory

Memory belongs to what we might call the shake and bake school of movie-making. That is, you take the ingredients of a successful movie of a certain kind — or even, as in this case, of more than one kind — put them together in a bag and shake them up. The director, Bennett Davlin, is also the co-producer and is adapting his own novel (with the help of Anthony Badalucco). As the creative control is so closely-held, we must suppose that the random assortment of themes, images and plot fragments he has put into the bag are his own idea and not something foisted on him by a studio but something he has chosen himself just to have fun with. He obviously doesn’t feel any need to connect anything plausibly with anything else. Here, as nearly as I can make it out, is his recipe.

First, take a mysterious corpse marked with symbols of some ancient people or religion and a bag of stuff containing clues as to the corpse’s life and how he got to be a corpse.

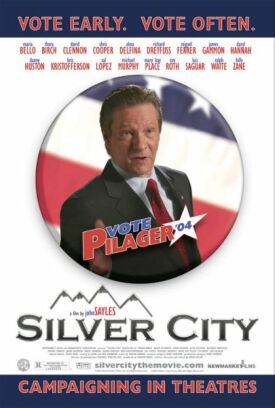

Add to that the hero, a Harvard-trained doctor named Taylor Briggs (Billy Zane) who, only ten years out of med school, has his own research institute dedicated to the causes and potential cures of Alzheimer’s disease — from which, by the way, his mother is a sufferer.

Now add an ethnic (Asian fusion?) side-kick, Dr Deepra Chang (Terry Chen), to serve as the voice of science and skepticism when the hero starts developing his wild and unsubstantiated theories — which, of course, will all turn out to be true.

Set the plot in motion by having the hero prick his finger through his rubber gloves on something in the corpse’s bag of stuff. Soon after, he starts to have powerful hallucinations.

In the first instance, the hallucinations will appear to be caused by a mysterious substance with which the corpse’s stuff is dusted. We’ll call this magic powder “magic powder.” It defies scientific analysis.

Science must also be baffled by the corpse’s brain scan, which is “something we have never seen before” — a kind of cancer that seems to target only the memory centers.

With no scientific explanation for his hallucinations, the hero can then pursue his investigations into what might be causing them by looking into ancient religious lore. He discovers the corpse’s name and a master’s thesis, secreted in the bag of stuff, into the same religious lore.

The hero becomes convinced of something that everyone else thinks of as a psychotic delusion — namely, that he is seeing in his hallucinations the experiences of his ancestors through their eyes — again, he is right and medical science is wrong.

So far, so predictably made of psycho-thriller stuff. But at this point, the film-makers must have decided that the ingredients had to be spiced up by the addition of that other psycho-movie staple and sure-fire commercial property, a serial killer — a man who, wearing a mask and a black Burberry raincoat, features in all the hero’s hallucinations. The ancient religious lore and the hero’s hunches suggest that this mysterious figure is his own father, whom he never knew. Being a psycho, the serial killer can indulge the obscure psycho-sexual hangups that drive him to kidnap little girls without the authors’ having to explain anything more about them than that he suffers from them.

At first, moreover, his predations are dated (with the help of a hallucinated newspaper) to 1971 — just before the hero’s birth. But then similar crimes are shown to have been committed down to the present day. So the detective story becomes a search not just for the hero’s origins or the identity of his dead father but for some living bad guy. Accordingly, the film introduces some new characters, all of them in loving relationships with the hero, as potential villains. These include two old friends of the hero’s mother, the avuncular Dr. Max Lichtenstein (Dennis Hopper) and the motherly Carol Hargrave (Ann-Margret), together with the hero’s love interest, the beautiful artist Stephanie Jacobs (Tricia Helfer), to whom he is first attracted because she has painted — coincidentally? — a figure who looks remarkably like the masked man in the Burberry raincoat. The bad guy is naturally the least likely of these.

This plethora of story fragments means that the hero’s detective work has to be hurried along, rather. Of course, it helps that the clues he needs are always surprisingly easy to find. Indeed, when he goes into a strange place to look for evidence, he usually finds it in the first place he looks, or even posted on the wall so he doesn’t have to look at all. In the end there is a kind of pretend dénouement in which the villain is unmasked and the secret of the hero’s parentage (sort of) revealed, but in fact everything is left up in the air. None of these random elements really has anything to do with any other, except by virtue of having been shaken up in the same bag. And if anyone can figure out a motive that makes any sense, either for the original killer- kidnapper in the Burberry raincoat or his heir, or what any of this has to do with memory except in the most superficial sense, please let me know.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.