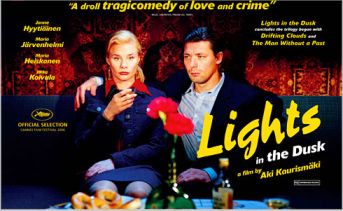

Lights in the Dusk (Laitakaupungin valot)

Albert Camus’s novel of 1942, L’étranger (or “The Outsider”), introduced the world to one of the first and most memorable in a long line of alienated heroes. The French- Algerian Meursault insisted on defining himself by the action — the killing of an Arab — which led to his execution. In accepting the responsibility for his own deed, he also asserted his freedom: he had chosen his fate and not had it foisted upon him. That self-assertion was also, naturally, a refusal to be a victim. But alienation has changed a bit in the last 65 years. Lights in the Dusk (Laitakaupungin valot), the third installment in what the Finnish director, Aki Kaurismäki, calls his “loser trilogy” (along with Drifting Clouds and The Man Without a Past) is about a man whose existence is virtually coterminous with his victimhood — and who seems to like it that way. The earlier films dealt with unemployment and homelessness, but this one is a bit more subtle. Its hero is not obviously the victim of economic, social or political forces nearly so much as he is of just not being very likable. At least not to the other people in the movie.

Koistinen (Janne Hyytiäinenis), is a security guard in Helsinki who for some reason never revealed to us is held in contempt by his fellow guards. They pretend not to know who he is, and when a group of them go out for a beer they pointedly exclude him. He seems to have no friends outside of work either. The only person who speaks to him is a woman called Aila (Maria Heiskanen) who serves him hot dogs from her wienie wagon. We get it. It’s a film about loneliness. But the underlying problem with Lights in the Dusk is that there is no apparent reason why Koistinen should be so lonely. He seems to want the fellowship of those around him but to be rebuffed for no reason. He is a loser only because Mr Kaurismäki needs him to be a loser.

And then he chooses to be an even bigger loser — in fact, a spectacularly successful loser.

One day a striking blonde woman, Mirja (Maria Järvenhelmi), accosts Koistinen as if to strike up a relationship. They go out to a movie, a meal and a disco together. Koistinen brags to Aila that he’s got a girlfriend. Mirja visits him at work and persuades him to take her, against regulations, on his rounds. She watches as he types in a security code at a jewelry shop. Then she puts a Mickey Finn in his coffee and steals his keys. Her accomplice, a gangster called Lindström (Ilkka Koivula), robs the jewelry shop, and Koistinen is fired. But he doesn’t tell the police anything about Mirja — just that he woke up in a car on the other side of the city with his keys missing. Even when Mirja visits him later and plants some of the jewels in his apartment so as to get him arrested for the robbery, he says nothing.

In other words, he chooses his fate as much as — or even more than — Meursault does. Yet the film still wants us to see him as a victim and not an existential hero. He in effect chooses to go to prison for two years. Is it out of a sense of misplaced chivalry towards the woman who has betrayed him? Is it love? Is it stupidity? Oddly, Mr Kaurismäki appears to have no interest in the answers to these questions. Rather, he presents this distinctly odd behavior as being just his hero’s nature. “Koistinen will never betray you,” Lindström tells Mirja. “He’s as loyal as a dog, the sentimental fool. It’s my genius to understand that.”

By the way, it’s also Lindström’s genius to understand Mirja’s loyalty to himself. She whines to him about what she is being asked to do to Koistinen by saying “What do you want of him? He’s a complete loser. Why am I doing this?”

“Because otherwise,” Lindström replies, “you’d have to work.”

Subsequently Mr. Kaurismäki adds a witty scene in which Mirja is seen doing the vacuuming in Lindström’s luxury apartment while he plays cards and drinks with a group of his buddies. She may not be a loser, but she’s got the loser’s — or the wife’s — masochistic need to be taken advantage of.

Meanwhile, the almost forgotten Aila writes and offers to visit Koistinen in prison. He tears the letter up unread. That makes him, too, the recipient of undeserved loyalty and Aila, perhaps, the champion of the victims because she’s the only one not victimizing someone else. Is Koistinen’s canine loyalty, then, supposed to be also distinctively feminine? Or is his spectacularly futile act of passive-aggression intended as a kind of existential self-assertion, like Meursault’s in going defiantly to his execution? Is it possible to assert your own existence by gratuitously sacrificing it? You be the judge, since the sacrifice is obviously intended to impress the audience rather than Mirja herself.

One thing an American will notice about this film is how much smoking there is. Everybody seems to smoke all the time — except for Mirja — and to look thoroughly miserable while doing it. Is this another way of courting disease, suffering and unhappiness? Koistinen’s early encounter with some drunken Russians, eagerly talking about literature, may be meant to suggest that passive-aggressive victimhood should be seen as a Finnish national tradition. But there is also a logical conundrum in the portrayal of Koistinen as a loser, since if he chooses victimhood, then he is presumably getting what he wants — which makes him a winner! That may be why Mr. Kaurismäki in the end suggests that Koistinen is prepared to cede the crown of martyrdom to Aila — which would, paradoxically, restore him to his place as biggest loser of all. It’s potentially a Woody Allen type comedy, but I don’t think Aki Kaurismäki is laughing.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.