Hollywood’s Hero Deficit

From The American of July/August 2008A spate of movies about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the war on terror came out last year, all of them hostile to U.S. involvement and all of them box-office flops. At the time there was a certain amount of soul-searching in the media as to why, when most Americans told pollsters they thought the Iraq war, at least, had been a mistake, they didn’t seem to want to go and see movies that sought to show them just how great a mistake it had been. The New York Times critic A.O. Scott cited what he called “the economically convenient idea that people go to the movies to escape the problems of the world rather than to confront them,” but acknowledged the possibility that America’s opposition to the war “finds its truest expression in the wish that the whole thing would just go away, rather than in an appetite for critical films.”

Without denying that insight, I would like to propose another explanation: American movies have forgotten how to portray heroism, while a large part of their disappearing audience still wants to see celluloid heroes. I mean real heroes, unqualified heroes, not those who have dominated American cinema over the past 30 years and who can be classified as one of three types: the whistle-blower hero, the victim hero, and the cartoon or superhero. The heroes of most of last year’s flopperoos belonged to one of the first two types, although, according to Scott, the only one that made any money, The Kingdom, starred “a team of superheroes” on the loose in Saudi Arabia. What kind of box office might have been done by a movie that offered up a real hero?

There’s no way of telling, because there haven’t been any real movie heroes for a generation. This fact has been disguised from us partly because of the popularity of the superhero but also because Hollywood has continued to make war movies and Westerns, the biggest generators of movie heroism, that are superficially similar to those of the past but different in ways that are undetectable to their mostly young audiences, who have no memory of anything else. In an otherwise excellent article in Vanity Fair about “chick-flicks,” James Wolcott recently wrote that, like the chick-flick, “the Western is also a genre that’s often pronounced dead and buried only to be dug up again and propped against the barn door — witness 2007’s 3:10 to Yuma, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, and No Country for Old Men.”

Wolcott is far from being the first to express such an opinion, but neither he nor anyone else appears to have noticed the principal way in which the movies he mentions differ from those of 50 years ago. None of them has anything like a real hero, though all three have charismatic villains, played by Russell Crowe, Brad Pitt, and Javier Bardem, respectively. The title tells us what to think of the would-be hero of The Assassination of Jesse James, played by Casey Affleck. He’s a creep, a stalker, and a traitor, as well as a coward. No Country has one really sympathetic character, the aging sheriff played by Tommy Lee Jones, who is as helpless against the bad guy as everyone else is. Next to the sexy and invincible serial killer, a kind of inverted superhero played by Bardem, he is reduced to being just another victim hero, maundering on about what a nasty old world it is.

But it is 3:10 to Yuma that offers the most interesting contrast between the old-fashioned sort of Western and the new breed. It was a remake of a movie first made in 1957, directed by Delmer Daves and starring Glenn Ford and Van Heflin. Like so many other Westerns of the period, it was a parable of the heroism of the ordinary people who brought civilization, peace, and prosperity to the Wild West. Heflin’s character, Dan Evans, is a simple farmer in danger of losing his farm to drought who, for the $200 it would take to pay the mortgage, accepts the task of escorting Ford’s Ben Wade, a dangerous killer, to catch the eponymous train to trial. At a moment when it looks as if he is sure to die in the attempt, Evans explains to his wife that he is no longer escorting the prisoner for the money but as a civic duty. “The town drunk gave his life because he thought people should be able to live in peace and decency together,” he said. “Can I do less?”

Needless to say, there is no comparable line in the remake. The Dan Evans of 2007, played by Christian Bale, is an almost helpless victim, a Civil War veteran who lost his leg in a friendly- fire incident and whose motivation would remain merely mercenary but for the fact that, like us, he is meant to become rather fond of Crowe’s fascinating Wade — and vice versa. James Mangold, the director of the remake, has turned it into a meet-cute buddy picture. In the original, Evans stands four-square for due process and saves Wade from a vigilante. Ford’s Wade, having the rough sense of frontier honor of old-fashioned Western villains, repays the favor, even at the cost of having to make the train. He doesn’t like owing anything to anyone, he says. The remake ends with a general shootout in which it is unclear why anyone, especially Wade, does what he does. Poor Evans remains only a victim.

Both films are typical of their times. The 1957 version shows moral earnestness, an optimistic belief in civilized standards, and an unabashed portrayal of heroism. These things are lacking in its 2007 counterpart. In this it is like the other two new Westerns, or the HBO series “Deadwood.” Its moral landscape is the war of each against all that we see on the lawless and violent streets of American Gangster or other films with a contemporary setting. The Wild West has been resurrected not as a story of taming the wilderness, both external and internal, on behalf of decency and civilization, but as a convenient synecdoche for that dark, amoral, and timelessly violent world that all art worthy of the name today must presuppose. Where there is no hope of a better world, there can be little to distinguish heroes from villains.

That’s why the American movie hero — who once so impressed the world that he personified heroism for people far beyond our borders — has been missing in action for decades. From the days of Tom Mix and other silent-screen cowboys up until the 1970s, America’s heroes were the world’s heroes. During and after World War II, real-life heroes themselves often looked to the likes of John Wayne or Gary Cooper to see what a hero was supposed to look and act like. Such men hardly exist anymore, except in old movies. In the early 1970s, there were many paranoiac films influenced by the popular take on Vietnam and Watergate. In Alan J. Pakula’s The Parallax View (1974), Sydney Pollack’s Three Days of the Condor (1975), or Peter Hyams’s Capricorn One (1978), not to mention Pakula’s All the President’s Men (1976), government, corporate, and civic leaders are bad guys, while heroism, now the province of lawyers or journalists rather than soldiers or cowboys, can only hope to unmask them.

Here was the origin of the whistle-blower hero who, however noble in other ways, can’t help being a rat, a betrayers of friends and colleagues, and self-righteous in proportion, which would seem to limit his appeal. Yet down the years from Norma Rae (1979) through The Insider (1999), Erin Brockovich (2000), the Bourne trilogy, and last year’s Michael Clayton, behind every whistle-blower hero has been the assumption that the public realm is inescapably corrupt. Once populated by heroes whose job it was to tangle with and triumph over the villains, the institutions that support the community have now been abandoned to the villains. The hero stands alone against corruption so massive that he cannot hope to do anything more than expose it, not end it. This makes him, also, a victim hero. He may also, like Jason Bourne, morph into a superhero and so hit the post-heroic heroism trifecta.

The vogue of the superhero dates to the late ’70s and early ’80s when, in the Star Wars and “Indiana Jones” movies — the latest of which, starring a geriatric Harrison Ford, came out this spring — the movie hero paid the price of his continued existence in Hollywood by living out his cinematic existence in a galaxy far, far away. Like Superman, whose first feature-film incarnation was in 1978, these heroes were unashamed of their cartoon origins and, therefore, their detachment from reality. Often muscle-men, like Arnold Schwarzenegger or Sylvester Stallone, they even looked unreal. Wayne and Cooper had, of course, been imposing physical presences on and off screen, but no one would have mistaken either of them for bulgy, oiled-up Mr. Americas. Nowadays, even so traditional a heroic story as that of Thermopylae finds its translation (in 300) into contemporary terms as beefcake.

The doomed Spartans were also examples of the victim hero who was the staple of the Vietnam War films, beginning with Coming Home and The Deer Hunter and continuing through Apocalypse Now, Platoon, Full Metal Jacket, Hamburger Hill, Born on the Fourth of July, and others. Like the superhero, the victim hero did not invite emulation — though hints of some nameless hidden trauma, sometimes self-inflicted like drug or alcohol addiction, were among the hallmarks of “cool” masculinity. Thus he might also overlap with the whistle-blower hero who, like Warren Beatty’s character in The Parallax View, was caught and destroyed by the forces of evil, or with the cartoon hero who suffered childhood trauma, as in Batman Begins, or undergoes torture, as in Braveheart.

The point of all three of the kinds of hero in which Hollywood has specialized over the last 35 years has been to make sure that heroism can continue to exist only on a plane far removed from the daily lives of the audience. It is hard not to speculate that this is because of a quasi-political aversion on the part of filmmakers to suggesting to the audience that real-life heroism was something to which it, too, could aspire. The subtext of films featuring the whistle-blower hero, the cartoon hero, and the victim hero is that heroism — heroism of the, say, Gary Cooper type — belongs to the public and communal sphere, now universally supposed to be cruel and corrupt, and therefore is really no longer possible or even, perhaps, desirable.

|

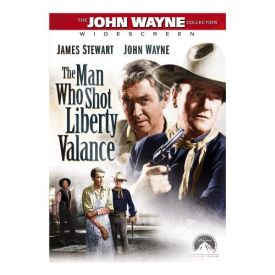

That seems to have been the point of the great John Ford film of 1962 called The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In it, John Wayne plays rancher Tom Doniphon in the Wild West town of Shinbone, which is still part of a territory not admitted to statehood and has only a comically feckless Andy Devine resembling anything like a duly constituted authority. Shinbone is terrorized by an outlaw named Liberty Valance, played by the great Lee Marvin. An idealistic lawyer named Ransom Stoddard (James Stewart) comes to town to practice his profession only to find that there is no law there. In fact, he himself is robbed by Liberty on his way into town, yet he can find no one there who thinks that this is any of his business, or that it is even possible for this outlaw to be brought to justice. The law is helpless where there is no law enforcement. As Doniphon advises the newcomer, “Out here men take care of their own problems.”

Doniphon is the only man in town capable of standing up to Liberty, but as he himself hasn’t been robbed he doesn’t quite see why anyone else being robbed, let alone this geeky stranger, should be any business of his. Eventually, the idea of a larger civic responsibility begins to sink in — and, with it, a sense that it has become incumbent on him to do what no one else can do. Yet it can only be done outside the law, which remains powerless. This puts Doniphon and Liberty (the name is of course significant) on the same side. Both are outlaws whose would-be heroic struggle has no place in a civilized community. When Wayne triumphs, a way must be found for the townspeople to pretend that it is the law which has rid them of the depredations of Liberty and his gang, and a way duly is found. Stoddard is hailed as a hero and Doniphon, the real hero, is forgotten.

Ford’s film was a parable less of the coming of civilization to the West than of the cultural transformation that was taking place in the postwar period in America and elsewhere — a transformation which resulted in an early but unmistakable foreshadowing of the death of the hero in the 1970s. The heroes who had won the Second World War commonly didn’t want to be heroes. They wanted to believe that they had been fighting for “a better world” (as it was so often formulated), by which they meant, among other things, a world that would have no need of heroes. The idea went back to Woodrow Wilson’s characterization of World War I as “a war to end all wars,” and this became the enduring dream behind the League of Nations and, after the setback of World War II, its successor body, the United Nations. War had become a shameful thing simply as such and irrespective of the justice of the cause in which it was waged or the net humanitarian good it might accomplish.

As a result of this increasingly influential cultural attitude, the movie hero was already beginning to become a more and more ambiguous figure in the immediate postwar period. The kind of clean-living, pious hero portrayed by Cooper in the pre-war Sergeant York (1941) — which celebrated an American hero of the First World War — gave way to the isolated and magnificent but dubious postwar figure of Cooper’s Marshal Will Kane in High Noon. The heroics of Sergeant York were seen as having been performed on behalf of a community and a nation — two-thirds of the film is spent introducing us to his hometown of Pall Mall, Tennessee — which are as properly grateful to him as he is devoted to them. Kane’s deeds are performed in spite of and in opposition to the will of the community he serves and more to satisfy a personal standard of honor than a sense of duty to such a pack of ingrates. The film ends with his dropping his badge in the dust and leaving town for good.

Similarly, John Wayne’s Ringo Kid in Ford’s Stagecoach of 1939 may be a convict, but he wins our hearts not only by being handy with a gun but also by his willingness to form an ad hoc community with his fellow passengers when they are attacked by Indians and by his broad- mindedness and chivalry toward a “fallen” woman. But in such postwar roles as Tom Dunson in Red River (1948), Sergeant John Stryker in The Sands of Iwo Jima (1949), or Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956), Wayne was portrayed as a lonely and isolated figure, living by a personal code, like Kane, but also like him in being more or less mistrusted and excluded from the community of those on whose behalf his heroic deeds are performed. In The Sands of Iwo Jima, Wayne’s attachment to a pre-war idea of what it meant to be a U.S. Marine even suggested that, in spite of the film’s admiration for his heroism and leadership, it finally saw him as a throwback who could have no place in the postwar world.

The greatest of the postwar contributions to the eventual decline and fall of the American movie hero came from what the French called the films noirs of the 1940s and 1950s. The noir hero was a prototype for all three of the heroes who have dominated American movies since the 1970s. Alone and without roots in any community, he lived in an urban twilight where few if any people could be trusted. Often a criminal himself, his real job was to expose a larger corruption and criminality than his own, and to suffer from it. In his most perfect incarnation, a private eye such as Sam Spade or Philip Marlowe — both played by Humphrey Bogart in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and The Big Sleep (1946) — he even had something like super-heroic powers. The noir film didn’t survive its period, however, and to my eye the many attempts to revive it since Chinatown (1974) have all failed.

The reason, I think, was that in the noir pictures there was always a sense — enforced to some extent by the Hays Code that aimed to uphold high moral standards and was still in force at the time — that however hated and resented the moral order enforced by the social and political powers-that-be, it was still a genuine moral order and not just the greed, viciousness, and violence of those who happened to hold power. Though the antihero whose flowering we have seen in our own time was there in embryo, it still left open the possibility of goodness and decency, not just on the part of individuals but of a community. That’s what it took for Dan Evans in the 1957 version of 3:10 to Yuma to be a hero: the idea that his courage was for the sake of a belief that “people should be able to live in peace and decency together.” Without this belief in a community where power is not antithetical to the good and the decent but the means of its advancement, neither the war films nor the Westerns of our own time will ever be able to give us any but a debased sort of heroism.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.