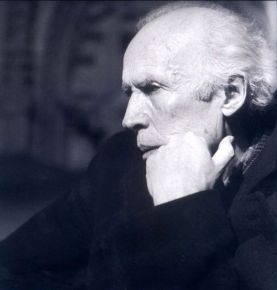

Reality Without Rohmer

From The American SpectatorEric Rohmer

Eric Rohmer, to my mind one of the three or four greatest geniuses of the cinema there has ever been, died in the same week that James Cameron’s Avatar rocketed past Star Wars to become the third highest grossing picture, domestically, in the history of the American movie industry. As I write, it seems certain to overtake not just The Dark Knight at number two but even Mr Cameron’s own Titanic, which has made $1.8 billion (so far) world-wide, as the biggest-selling movie of all time. Long-time readers who may remember what sort of opinion I had of Titanic and The Dark Knight, not to mention the last Star Wars movie I bothered to see, will perhaps not be surprised that I found little to like in a movie about a planet populated by a whole race of giant blue anthropoids almost as annoying as and way more self-righteous than Jar Jar Binks. Nor, of course, is there any news in the fact that none of the late Mr Rohmer’s films ever pulled down so much as a thousandth part of the American box office of these comic-book movies.

Yet it is worth pointing out that this embarrassing contrast is not simply a matter of the difference between popular and élite tastes. In the golden age of Hollywood between 1930 and 1960 there was also a gap between the most popular and the best movies, but it was nothing like as wide as it is today, either on the artistic or on the financial side. The former box office champ, Gone With the Wind, wasn’t the best that Hollywood could produce, even in the same year — which also saw the release of Ninotchka, Stagecoach and Drums Along the Mohawk, not to mention La R gle du Jeu and Le Jour Se L ve from the land of Eric Rohmer — but it wasn’t a bad movie and certainly not abysmally bad in the way that Avatar is for anyone who, like me, still has any residual expectation that movies will, or at least ought to, look a bit like real life.

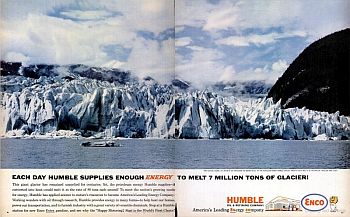

We must suppose that those who are flocking to see Avatar, like those who flocked to see Titanic and The Dark Knight before it, aren’t expecting to see anything that looks like real life. Many may not even know what real life looks like. For young teenagers who have spent almost as much of their lives in front of a screen as they have in any active dealings with the unplugged world, the comic book world must be as real as, if not more real than, anything else they know about. At least they have an excuse for their addiction to fantasy. Grown-ups who ought to know better now prefer it to reality as well. Even the élite culture is infected by the fantasy bug, as I pointed out here last month (see “The End of History” in The American Spectator of February, 2010). Yet the fantastical romance is not a just a new art form, fashionable today as Westerns or historical dramas were a generation or two ago, but something quite different, in fact, a denial of the whole Western tradition of art.

|

It obviously wasn’t going to break any box office records, but when I went to see Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier broadcast live from the Metropolitan Opera at my local multiplex in January it was sold out. In fact, there was an overflow showing a few days later for those who couldn’t get in to the simultaneous broadcast. Western culture can’t be quite dead, you might think, if there was this kind of throng assembled to watch one of the greatest of 20th century operas done in impeccable period costumes. Strauss and his librettist, Hugo von Hoffmansthal, writing in 1911, had set their story more than a century earlier, in 18th century Vienna, because the formalities of the Hapsburg court and its aristocratic hangers-on had largely fallen away by their own time and they needed them to say what they had to say about love and marriage and youth and age and joy and loss. This artificiality created a necessary distance between opera and audience that was reflected in the staging.

But from the first scene of Rosenkavalier, the movie, that artificiality was swept away. As in 1911, the opening scene presented two lovers, Renée Fleming as the Marschallin, or wife of a field marshal, and her ardent teenage paramour, Octavian, played as a “trouser” role by Susan Graham, in bed at an obviously post-coital moment. What had changed was that the unforgiving camera’s close-up of this moment showed us as no stage production ever could that these were two women, not an older woman and wife — die alte Fürstin Resi, as she calls herself, is probably in her mid-30s — and her impetuous boy-toy. And even if you could shake off the illusion that this was now to be about a lesbian affair, you had already been taken by the camera into a more intimate relationship with these two people being intimate than is consistent with an appreciation of the scene’s emotional meaning.

This meaning had formerly essentially to do with the sex and age difference and hardly at all with the sex (in our contemporary sense of the term) which now became paramount. Here was yet another “cougar” strutting her stuff — and her epicene boy-toy — for the camera, albeit in a more demure fashion than we have lately become accustomed to. If that’s where you’re starting from, I don’t see how you’re ever going to get properly to the moment of letting go in the third act, a letting go of life as well as love, which is what the opera is leading up to. C’mon, Resi baby, Quinquin may be off with Sophie (Christine Schäfer), but there’s plenty of life in the old girl yet, if you know what I mean.

The close-up, in other words, is a reminder that what we are looking at is something that, in real life, no one else would or could see. That glimpse instantly takes with it everything else out of the opera’s public realm of love and loss and into the private one of bedroom fumblings. That’s what movies do. They hold out to us the promise of seeing what would otherwise be hidden. If all art, as Pater said, aspires to the condition of music, then all cinema aspires to the condition of pornography — that is, the excitement it creates in us is all but inseparable from the hope of seeing what reticence or modesty or discretion would normally keep from the public view. Years ago, audiences and film-makers shared an understanding that the camera would restrain itself, as people mostly did too, from an intrusive penetration of the veil that kept public and private separate. That understanding is now of course long gone.

As a result, movie-making has led the way for the other arts to find ever more “transgressive” ways of seeing, or making us think we see, what otherwise we couldn’t or wouldn’t see. Who, with that in prospect wants to settle for the acquiescence in reality that is the point of Rosenkavalier or a Rohmer picture? In all his films, what we see is nearly always what we would see if we met his characters in real life. People reveal themselves as they did in the movies of old, through conversation and social interaction with each other, not through the fake confidences of voiceover and authorial secret-sharing designed, as in Avatar, to create the by-now tired illusion that we, all umpteen millions of us, are seeing what others cannot see — and in 3-D! Such short-cuts to an ersatz reality are what has robbed us of the Western mimetic tradition.

Once we expected from art an imitation of something we already knew. If the imitation was skillful enough, it would also reveal things we did not know about the things we already knew, or things that we immediately recognized as true, even if we did not know them before. “It’s the way of the world,” as the Marschallin says in Rosenkavalier. But now we’re all bored with the way of the world and we want to know about the ways of other worlds. Avatar, like all those other best-selling fantasies from Batman to Harry Potter, is not an imitation of anything — least of all of the dispossession of the North American Indians by Western colonialists of which it attempts a clumsy and unpersuasive analogy — but a new thing altogether. I know I must be one of the few who are not quite happy with this bargain, but if you’d like to know what we’ve lost in order to gain this new heaven, new earth, so much more imaginatively congenial to most of us than the old one, try watching a movie by Eric Rohmer.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.