In Our Bitter World

From The American SpectatorNo longer admirable

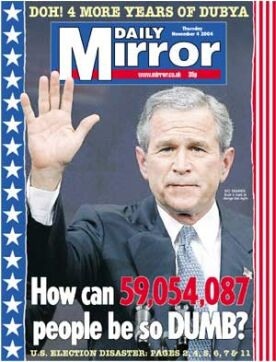

As our esteemed editor, R. Emmett Tyrrell, Jr., has recently pointed out, in the course of announcing the death of liberalism, “the condition of our political discourse” today is not just “rancorous” or “toxic” — as so many are wont to complain it is and as, more or less, it always has been — but “worse than that. It is nonexistent.” His prime example is the New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, one of three men to have won Nobel Prizes, the other two being Jimmy Carter and Al Gore, for not being George W. Bush — which would seem to be a greater distinction for President Bush than it is for any of them. Lately, Professor Krugman has been training his sights on Congressman Paul Ryan of Wisconsin whose proposals for eliminating the alarmingly large and seemingly perpetual deficit between federal outgoings and federal incomings the Professor regards with Olympian contempt. The Congressman is not just wrong, in his view, but so wrong that he must be either knave or fool to persist in such wrongness. So wrong that he (and those of us who think like him) are not worth the Professor’s arguing or engaging with, or even speaking to over a friendly luncheon repast. So wrong that, having made a spectacle of himself only three months previously by falsely blaming Republican incivility for the mayhem wrought in Tuscon Arizona by a clearly deranged young man, the Professor was now himself crying — “let’s not be civil” to Republicans.

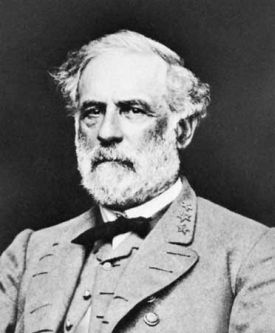

Yet I think it would be a mistake to laugh at this Nobel Prize-winning economist as much as he deserves to be laughed at, since he stands for the broader trend that Mr Tyrrell was indicating and that shows up more and more frequently not only on the op ed pages of our major newspapers but wherever political dialogue would once have been expected to be carried on in a seemly and rational fashion: the trend, that is, to treat those with whom we disagree not just as intellectually but as morally befuddled. Thus, to cite just a few random examples, one columnist tells us that “the only possible humane response” to the terrorist prison at Guantanamo is the left-wing obsession with closing it down. Another insists that Robert E. Lee, a man who for more than a century has been much admired by friend and foe alike, “cannot be admired.” A prominent law firm with no scruples about defending terrorists withdraws from the defense of the Defense of Marriage Act for fear of being stigmatized and boycotted by the Puritans of the New Decency who consider marriage as it has been, minimally, understood since pre-historic times as “un-American” and, forsooth, “indefensible.”

Where do these strange and frightening certainties come from? Why do we emulate such rhetorical totalitarians today rather than those who are merely blessed with facility in reasoning or felicity in phrasing? In a handsome tribute to his friend, Christopher Hitchens, in The Guardian, Martin Amis recently wrote that he “is one of the most terrifying rhetoricians that the world has yet seen. Lenin used to boast that his objective, in debate, was not rebuttal and then refutation: it was the ‘destruction’ of his interlocutor. This isn’t Christopher’s policy — but it is his practice.” Fortunately, the rest of the article does not bear out this bizarre and characteristically hyperbolical compliment. Mr Hitchens, at least on Mr Amis’s own showing, turns out only to be a wit — which ought to be plenty enough for anyone engaged as a public controversialist — and not a Lenin after all. Yet Mr Amis has put his finger on the sort of rhetorical style that is now most prized among our rhetoricians, who may not reduce their opponents to nullity but often act as if they have done so. In their own mind they are triumphant because, in a sense, the debate (such as it is) has taken place only in their own mind in the first place. What they have answered is not their opponents’ actual beliefs but what they have, by paraphrase and analogy, pretended they believe.

In short, reality itself has become multiple and proprietary. It’s now “my reality” or “your reality.” Instead of meaning “what we can agree on” the word has now come to mean “what I think” — since there is presumptively no longer anything, or anything important, that we can agree on. Nowadays, our critics, columnists and pundits can no longer be content merely to offer us their opinions. They insist on laying down the law. What they think is now what we — at least if we are decent and reasonably intelligent people — must think as well, and not to think as they think is therefore tantamount to classing ourselves with the venal or the idiotic. In effect, they become propagandists for their version of reality, which is like the reality that we all used to share but with the characteristic distortions and distensions of ideology.

In The Abolition of Man, C.S. Lewis writes that what we call ideologies “all consist of fragments from the Tao” — the word by which he designates the moral tradition of the human race — “itself, arbitrarily wrenched from their context in the whole and then swollen to madness in their isolation, yet still owing to the Tao and to it alone such validity as they possess.” Thus ideologues of the left abstract certain virtues from the catalogue that we have inherited from traditional moral and religious thinking, virtues like compassion and generosity, and make them into the only virtues that matter. Thus does reality transform itself from an enormous, hard-to-understand and harder to live up to patrimony into a simple program of political action. Thus does it have the proprietary stamp put upon it. This has now become such a common rhetorical phenomenon that even we remaining traditionalists who want to retain as much as possible of what Philip Larkin called “that vast, moth-eaten musical brocade” of Christianity are accused of being ideologues who only wish to impose our version of reality upon our fellow creatures.

The irony of those who denounce our Christian inheritance in the name of some ideology or other is that theirs is even more an appeal to faith than that which they oppose. The faith of our fathers was held onto for a hundred generations in spite of dungeon, fire and sword; that of their successors rarely outlives the rival theorists and ideologues themselves. And even where it does so, as in the case of Karl Marx, its theories are subject to endless modifications and revisions by the heirs of the prophet who must try to adapt them to changing intellectual fashions. Belief is required in both cases, but it seems to me much more difficult to sustain in the second than in the first.

|

A further irony is that, as competing realities jostle each other in the marketplace of ideas, the idea of reality itself is devalued. When our public moralists of the op-ed pages confidently announce that theirs is the only way of looking at things, no one takes them seriously except for those who already agree with them and share their outlook on reality. Even they must be dimly aware of the price to be paid for their confident assertions of omniscience. But just as they must close their eyes to inconvenient realities that do not fit their theories, so they must close their eyes to their own loss of credibility outside their ever more tightly-described intellectual circles. This is the state of rhetorical affairs which has reduced public debate in the media and among politicians to its current pitiable state, symbolized by the public prominence of Paul Krugman.

But the greatest irony of all may be that people’s awareness of the unreality of contemporary “realities” may lead to a comeback for reality itself, or, as it once was known, nature. As Horace put it: Naturam expellas furca, tamen usque revenit or: you can heave nature out with a pitchfork, and yet she will come back again. That is what the Danish director Suzanne Bier shows us happening in her brilliant film, In a Better World. The title represents a toning down of the bitter irony in the Danish Hævnen, which is a double allusion to the ideological utopianism with which the main body of the film plays and which it mercilessly exposes and the Christian doctrine of the afterlife that such utopianism attempts to displace. In the film’s interlinked stories of a compassionate doctor treating the poor in Africa, his son being bullied at school back in Denmark and another boy who has lost his mother, we encounter again and again Mr Tyrrell’s moribund liberalism in the form of cant about what in America would be called “the cycle of violence” — and again and again it is shown to be sadly inadequate to the reality that is real and not just what liberal ideologues want to believe. See it if you don’t see anything else this year.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.