Toast

Whenever I hear someone say that someone else is toast, meaning he’s dead, fired, finished, kaput or has lost something only less precious than his life or his job, I have a little mental hiccup. It is a way of making light of serious things — nothing wrong with that, of course, so long as they’re your own serious things — or, less benignly, expressing one’s indifference to things which are serious to others. Somehow it seemed to fit with what we knew of Ted Turner when we heard some years ago that he had fired his own son at a family dinner by telling him: “You’re toast.” Rhetorically, it’s also confusing. Presumably the expression derives from the fact that toast, like meat (stick a fork in him), is something that’s “done,” but the pun leaves the visual imagination grasping at airy nothing, since the image of toast itself conveys no sense of loss or conclusion, let alone the devastation the expression is often used to denote. Rather the reverse. Toast is the ultimate comfort food.

Toast and marmalade for tea,

Sailing ships upon the sea

Aren’t lovelier than you.

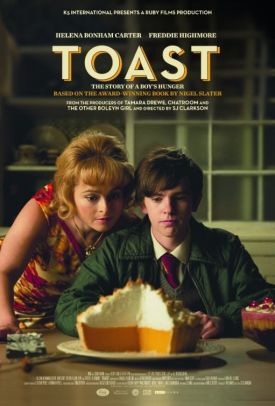

Or so sang Tin Tin — no, not that one but the one-hit wonder Australian group — 40 years ago. And that’s how toast is treated in S.J. Clarkson’s movie, written by Lee Hall (Billy Elliott), called Toast. Set in the British Midlands in the 1960s, the movie is meant to evoke the period and the place, partly with a soundtrack laden with the plaintive songs of Dusty Springfield and partly with continual reminders of the dreadful British diet of that era. It’s because there’s so little else that’s good to eat that, as the movie’s nine year old hero and narrator, Nigel Slater (Oscar Kennedy), tells us, you’ve got to love somebody who makes you toast.

He’s talking about his mother (Victoria Hamilton), who is pretty much incapable of making him anything else, in spite of all the encouragement young Nigel can give to her unavailing efforts in the kitchen. But mum is toast too, in the other sense. She’s got some kind of lung condition that poor Nigel soon must realize is going to shorten her life and his childhood. Once she’s gone, it’s just him and his irascible dad (Ken Stott), a factory manager from Wolverhampton, near Birmingham — a man whose bad temper (as his son speculates) may be owing to the fact that he has hardly ever had a decent meal. Nigel is the first to get the idea that dad’s affections are to be wooed and won in the kitchen, but he soon finds himself up against a formidable competitor in the shapely form of Mrs. Potter (Helena Bonham Carter), who comes into the house as the cleaning woman but is rapidly promoted to companion, mistress and wife. Obviously, it’s not just her cooking that Nigel can’t compete with.

But the fact appears to have given him a lifelong grievance. Mr Slater is a popular food writer and TV personality in Britain, and the memoir on which the movie is based seems to have been written in answer to his fans’ urgent request. Tell us, Nigel, how you got to be so interested in food. And so Nigel does. But of course most of us who want to hear from him — if we do want to hear from him — do so not out of any affection for or curiosity about Nigel Slater. Most of us, at least in America, have never heard of the guy. We watch because we suppose he has an engaging human story to tell, and up to a point he does. In this he is helped immeasurably on the screen by tremendous performances not only from Miss Bonham-Carter, Mr Stott and young Master Kennedy but also Freddy Highmore (of Finding Neverland) as the teenage Nigel and a brilliant young actor called Frasier Huckle as nine-year-old Nigel’s best friend Warrel who almost steals the show. “Normal families are over-rated,” he tells Nigel consolingly. “You will probably grow up to be interesting.”

Doubtless he did. But the movie ends up leaving a bad taste in the mouth — and not only on account of Mr Highmore’s gay kiss with a character introduced solely for that purpose. We probably could have guessed that the boy was going to grow up to be gay, as well as interesting, but the subject is only brought up in this way in order to be dropped again. It’s as if he wants to tell us: forget about love. Let’s get back to the movie’s real subject, which is hate. The narrative dynamic of this kind of movie requires that its portrait of Mrs Potter should be an affectionate, if not uncritical one. It’s not. Quite the reverse. Nigel Slater’s hatred for his step-mother has obviously festered for forty years and comes out scalding on the screen.

Well, she regarded him as a rival for his father’s affections, which of course he was, and she warned him to stay off her “patch” in the kitchen. But what he really can’t forgive is that she was “common,” as his beloved mother would have said. As common as a pork pie. Actually, it’s her commonness, among other things, which makes Mrs Potter interesting and even lovable to me, and there is great poignancy at the end when she desperately tries to win Nigel’s affection, as she has won his father’s, in the only way she knows how. In the kitchen. This gives him the opportunity for a mean-spirited little triumph by spurning her from him. Today’s superchef can now claim that the kitchen is his patch. Nice for him, I guess, but not so nice for us. That after all these years later she is still nothing but hateful to Mr Slater — and, through him, to Messrs Hall and Clarkson who would have us feel the same — amounts to an emotional contradiction at the heart of the movie from which it cannot recover. Mrs Potter is toast, but then so is much of our sympathy for Nigel, or so it seems to me.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.