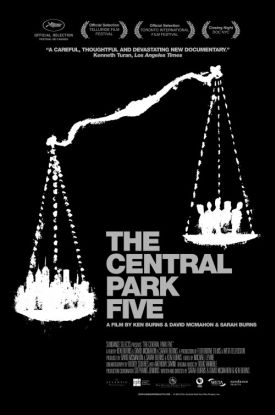

Central Park Five, The

Ken Burns’s documentary, The Central Park Five, based on a book by his daughter, Sarah Burns, tells the by-now pretty well-known story of the false conviction of five New York teenagers for the brutal rape in April of 1989 of a woman who for years was known only as “the Central Park jogger.” Subsequently we learned — her own book, I Am the Central Park Jogger (2003) spilled the beans — that her name was Trisha Meili and that, having made a recovery from her injuries that was little short of the media’s favorite epithet, “miraculous,” she might as well join in the public discussion that had surrounded her horrible experience from the beginning and that had during the same period, especially in the media, insisted on seeing it as somehow emblematic of all that was wrong with America. In this respect, if in no other, Mr and Miss Burns are carrying on in the same tradition, except that it is now the fate of the five not-guilty teens rather than that of the poor jogger which is significant, and racism rather than crime and social breakdown what it is significant of. “Oh,” as Homer Simpson says: “that.”

The film rounds up the usual suspects, too, focusing on the fault of the police and prosecutors who brought the case against the teens, on the gap between rich and poor in New York in the 1980s and the fear of crime that gripped the city in the period between the coming of crack to the streets of Bedford-Stuyvesant and Harlem in 1984 (I would argue much earlier than that) and the crackdown on crime under Mayor Rudolph Giuliani a decade later — which, so far as the film-makers are concerned, may or may not have had anything to do with the relative peace and safety in which New Yorkers live today. Understandably, they also show less interest in the question of the guilt of the innocent Five in several other incidents of assault and vandalism, which took place in the Park on the same evening and which they were originally arrested for. It’s obviously important for the sake of their story that the boys remain pristine in victimhood.

To be fair, the role played by the media and the media’s hype in what happened to them is mentioned in passing and Jim Dwyer, then a reporter with Newsday and now with The New York Times, offers a perfunctory mea culpa on their behalf. But the movie itself is evidence that hype is now our lingua franca. Mayor Ed Koch is shown calling the jogger case “the crime of the century,” as if it were still 1989 and he were still in office. For the most part the Burnses prefer to avert their eyes from the crucial role of the media in pushing for the false convictions, as they do from the fact that both the prosecutors who seem to have been the chief culprits (if culprits they were) in stitching up the Five, were female. So, too, the fear of “crime” that the film mentions was much less important in generating the popular energy that the case produced than the fear of rape specifically. Whether the racial or the sexual element in the case was the more important factor in generating the hype which, in turn, generated the need for a quick conviction may be a moot point, but there can be little doubt that the two were vitally connected. The film is thus weakened by its attempt to disentangle them in order to attribute the false convictions to racial inequality.

The result is that this study in popular hysteria is much less cogent or interesting than it might otherwise have been. We are left with the impression that the police identified the suspects and the prosecutors built their case against them simply out of malicious racism. The fact that none of those police or prosecutors chose to cooperate with this documentary cannot be quite unrelated, though a pending lawsuit against the city would have made that impossible in any case. Their presence would undoubtedly have helped in the effort to understand what happened, if we assume for a moment that understanding and not propaganda is the object of the film. The nearest it gets to an effort to arrive at any more persuasive explanation is the verdict of Jim Dwyer, who fingers “institutional protectionism” — a linguistic barbarism which refers, I take it, to the human tendency of police and prosecutors to close ranks in order to cover up their mistakes from public scrutiny.

The thing, if not the term, doubtless did play a part in bringing about both the injustice to the five boys and the further injustice of failing to make the effort to put it right. It was only when the actual rapist, Matias Reyes, came forward to confess more than a decade later that the case was reopened and the convictions overturned. But the indictment brought by the black historian, Craig Steven Wilder, against “society” — of which the Five’s convictions are said to have been a “mirror” — seems at least equally unjust. “Society” is much too easy a scapegoat for the faults of particular people who behaved badly. And if blame is to be allocated, let’s at least make sure that the media get their share. They were clearly complicit in the popular will to believe in a recrudescent savagery associated with such much-exercised journalistic terms as “Wilding” and “Wolf pack” which seemed to dehumanize the alleged criminals.

Like the crime itself, these words came to stand in the popular imagination for crime — assault and property crime as well as rape — committed just for the fun of it which, therefore, could be taken to signify a complete moral and social breakdown. As it turned out, however, rape was not ordinarily that kind of crime but one appealing to the criminal specialist, such as Matias Reyes, who was a serial rapist and murderer. But the media version lives on in the absurd contention of David Denby in The New Yorker that the film is “perhaps the most devastating portrait of contemporary social inequality to appear in an American documentary.” This is like calling Citizen Kane a devastating portrait of the dangers of sledding or Casablanca a devastating portrait of gambling in Vichy France. The fact that the suspects were from socially unfavored backgrounds was not quite irrelevant to their plight, but a society without disparities of wealth and power not being imaginable, we ought to have wit enough to look to our portraiture for something more specific to this case, such as media fear-mongering, and not a constant of the human condition.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.