As She Likes It

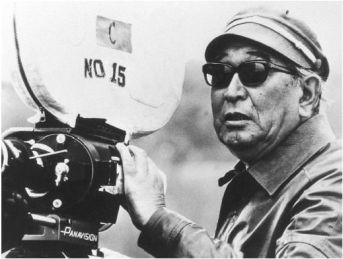

From The American SpectatorMark Rylance as Olivia

We hear that the state of Massachusetts has passed a law — “An Act Relative to Gender Identity” — requiring (among other things) that high school-aged boys who can persuade school authorities that they sincerely think they’re inwardly and in spite of anatomical evidence to the contrary really girls should be allowed to play sports with, go to the lavatory with, change their clothes with and shower with those who are “anatomically” female. The idea of the anatomical female itself suggests that anatomy is not quite a sufficient qualification for female status — any more than it is now, apparently, for male status. If anyone’s sex is elective, then everyone’s must be. And there we were thinking political correctness had gone mad when it only insisted that colleges spend as much on women’s sports as men’s. This new outbreak of ideology, if unchecked, seems likely to put an end to women’s sports altogether.

One mustn’t laugh at the “transgendered,” of course, but it may be hard to suppress a reaction to the spectacle of men impersonating women that has hitherto been thought “normal” and therefore culturally sanctioned. The drag queen, like the pantomime dame in the British theatrical tradition, still invites laughter, but those who take the “transitioning” from one sex to the other so seriously as to call upon the assistance of the surgeon’s knife are understandably offended by any who are so bold as to make light of their sexual aspirations. Even lefties have to be reminded of this, apparently, as we learned from the uproar in the British press recently when a columnist named Suzanne Moore wrote in the liberal New Statesman that, in her opinion, British women “are angry with ourselves for not being happier, not being loved properly and not having the ideal body shape — that of a Brazilian transsexual.”

Well, you’d think that at least male-to-female transsexuals, and not just Brazilian ones, would have been flattered to be told that they had the ideal female body shape. Isn’t that what they spend their lives trying to achieve? But I guess there’s no pleasing some people. They got all in a huff about their hurt feelings, so that Ms Moore’s pal, Julie Burchill, felt it incumbent on her to weigh in with a piece in the equally liberal Sunday Observer and hurt them some more, calling them “d***s in chicks’ clothing” and “bed-wetters in bad wigs.” This caused further commotion. So much so, indeed, that The Observer retracted the article, issuing a groveling apology for, in its editor’s words, having “got it wrong,” for once, in the course of what he described as its normal practice of “ventilating difficult debates and airing challenging views.”

The implication was that Ms Burchill had failed to be challenging enough when, clearly, the opposite was the case. There are limits, we see, to how far The Observer is prepared to ventilate and challenge, and they are drawn according to an arcane hierarchy of approved victimhood — now, as the state of Massachusetts has also recognized, very much including transsexuals. Mere anatomical females must carry less weight in demanding reparations from the patriarchy or in claiming a place near the top of the list of those politically approved interest groups — or media constituencies, as we might better call them — that can successfully claim a right to be protected from insulting or disobliging things others might say about them. That’s in addition to the right to shower with members of the sex to which they feel themselves to belong.

I wonder if enough research has been done on the connection between this new sympathy and respect we are all required to show to the transgendered and the recent decision by the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the United States armed forces officially to include females in combat units for the first time? As I point out in my book, Honor, A History, in one of the few historical examples where women have been deliberately thrown into combat, that of the 18th and 19th century warrior women of Dahomey, they seem to have been required to undergo a ritual sex change before being allowed to fight. My sources do not reveal whether any surgery or hormone treatment was involved in this procedure, but the very sensitive transsexual “community” might be interested to know of the potential for increasing their numbers and influence by recruiting among the soon-to-be warrior women of the USA — who, according to General Dempsey of the Joint Chiefs, seem likely not even to be required to do so many pull-ups as men, let alone show other forms of “anatomical” equality with them.

More and more it seems that the answer to Freud’s famous question — What do women want? — is that they want to be not so much equal to or even superior to men but indistinguishable from them. And yet, at the same time they want to be wooed and petted and cossetted by men, ever solicitous of their wants and wishes as Republicans and other extremist men are so often and so emphatically said, to their shame, not to be. Perhaps what women really want is to be homosexual men, as The Simpsons once suggested the gals of “Sex and the City” did. But then more and more men seem to want that too. Soon there won’t be enough gayness to go around — assuming we haven’t arrived at that point already.

Something like that was my among my first thoughts when I attended, on a trip to London recently, a really excellent production, transferred to the West End from Shakespeare’s Globe, of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night with an all-male cast. I don’t know how well you know this play, but it depends crucially on the impersonation by a young woman, named Viola, of a young man. In Shakespeare’s day, of course, this would have meant a boy playing a girl playing a boy, as in As You Like It and others of his plays, and this piquant state of sexual ambiguity was obviously part of what the production, directed by Tim Carroll was aiming at. Yet there was more to it than that. Though there was a fair bit of campery going on, especially in the case of Paul Chahidi’s scheming Maria, there was also a genuine attempt to imagine (or re-imagine) femininity for an age which has called the whole concept into question.

I’m thinking principally of Mark Rylance in the role of Olivia, the sad woman in whose house and messuage almost all the action takes place. She is wooed by Liam Brennan’s Count Orsino but finds herself falling hopelessly in love with the latter’s love messenger, the aforementioned Viola (Johnny Flynn), under the impression that she is a young man named Cesario. Mr Rylance, during his time as Artistic Director of the Globe, helped to pioneer the idea of gender-blind casting which has continued under the directorship of Dominic Dromgoole. A few years ago in this space (see “Culture Benders” in The American Spectator of November, 2008), I mentioned a production I had seen there of Troilus and Cressida in which several of the most important male roles, including those of the Greek kings Nestor, Odysseus and Agamemnon and the Trojan prince Aeneas were played by women.

In that case, the inevitably comic effect of the cross-dressing undermined any serious intention Shakespeare may have had in writing the play, but in the comic context of Twelfth Night the effect of Mr Rylance’s Olivia was just the opposite, producing instead a kind of liberation from our contemporary ideas of sexual roles. In other words, a woman nowadays couldn’t have got away with playing Olivia as he does, with such exquisite femininity. She would have had to be tougher and more mannish in order to uphold what we now imagine to be the honor of her sex, which no longer resides in sexual continence (as it once did) but in equality with men. Mark Rylance, however, is licensed by his temporary sex-change to go exploring in the old-fashioned and now-disreputable realms of sexual difference and inequality.

In the course of doing so, he reminds us that the meanings of Shakespeare are very much bound up with contemporary social conditions. This long-ago Englishman must have had an almost modern sense of the fluidity of sexual role playing — of the extent to which our ideas of “man” and “woman,” like those of the class to which they were always appended in his day, were what we would call “socially constructed.” Yet he also has a very un-modern sense of the necessity and even the beauty of such construction as a civilized human response to and imposition upon the perils of wild and chaotic nature — that same nature which we of the late modern period have foolishly grown into the habit of expecting to be our friend and benefactor. I might add that that expectation is where the transsexuals make their big mistake, but I’m afraid it would get me into trouble with the PC police.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.