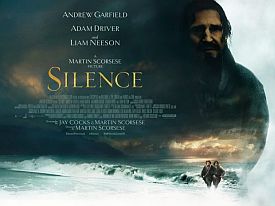

Silence

Not many years since, it would have seemed impossible for an American director with a popular following and a career filled with golden opinions from practically the whole critical fraternity to offer up to an admiring public an apologia on behalf of Japanese torturers and murderers of Christians, both foreign and domestic, even if both torturers and tortured lived almost 400 years ago. I suppose we have to thank multi-culturalism which, among its many other blessings, has taught us that there is virtually no behavior by people racially or religiously different from white, middle-class Americans or Europeans that cannot be excused on the grounds of cultural differences.

For the centuries do not matter. Our own ancestors who were the contemporaries of the Japanese persecutors and who bought and sold slaves can be and are condemned in the roundest terms, their sins being visited upon their descendants even to the ultimate generation. Likewise, the Spanish Inquisition remains a reproach to the Church half a millennium on, whereas the Japanese, who hadn’t even the excuse for their cruelty of being colonized by the West, are off the hook — at least so far as Mr Martin Scorsese is concerned. His Inquisitor, as he calls him (Issei Ogata) comes across as rather a sympathetic and even amusing character as he stands up for Japanese resistance to the alien creed.

The film is called Silence, and it begins with what I suppose is meant to be silence’s visual equivalent: a dark screen. But crickets on the soundtrack break the silence. It soon becomes evident that the real silence he has in mind is the silence of God in response to the cries of anguish from the tortured followers of Jesus, said to be His Son. The odd thing is that Jesus is not silent in this film. At a crucial moment (spoiler alert!), when a Portuguese Jesuit priest named Sebastião Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) is invited to put his foot on a holy image of Christ in order to save five Japanese Christians from a slow horrible death —hanging upside down in sacks and exsanguinated drop by drop — we are asked to believe that Father Rodrigues hears the voice of Jesus saying, “Go ahead. Step on me.”

So that’s all right then — as is, presumably, Father Seb’s apostasy and subsquent Japanization, along with that of his former mentor, Father Ferreira (Liam Neeson), who joins Jesus himself and the Japanese authorities, pleading a multicultural exemption from Christian belief, in persuading him to do it on compassionate grounds. Both priests are rewarded for their apostasy by being provided with Japanese wives and families along with Japanese clothes and Buddhist beliefs and become agents of the Inquisitor in keeping all other Christians out of the land of Nippon. We are allowed to suppose that Father Rodrigues, at least, continues secretly to harbor Christian beliefs, or superstitions if you prefer, to the end of his life, but that only serves as a further excuse for his apostasy — and for the Japanese insistence on it. At least their approach might be described as “Don’t ask, don’t tell.”

But hang on a minute. I’m only playing my own version of Mr Scorsese’s trick on you by trying to get you to see his movie through different eyes than his own — namely, those of a pre-Vatican II Catholic raised on stories of the saints and martyrs throughout two thousand years who were said to have gone joyfully to the rack, the scaffold, the flame or the grave rather than do what Father Rodrigues does in Silence. The point of principle on which this Jesuit priest is invited, quite literally, to stand is also the most superstitious (to modern eyes) and unnecessary of the church’s beliefs, that having to do with sanctified objects and images, and not anything we should regard, apart from the mere tradition of it, as desirable, let alone needful, to die for.

In other words, we have been prepared by the last 40 years of Western academic and media culture to pity and patronize Fr Rodrigues, not to identify ourselves with him in his trial of faith, though some will obviously do so anyway. In fairness to Mr Scorsese, he is only taking advantage of the fact that for any 21st century Catholic the mentality of someone willing to die, and allow others to die, rather than put his foot on a bas relief image of a holy man, however sacred the image or however much he may preserve some understanding of what it is to desecrate it, is almost as foreign as it is to a non-Catholic. There can be very few even of believers today who would not come to think, and a lot more quickly than Fr Seb does, that it was no big deal to take that step — particularly when you consider the alternative.

It’s all in how you look at it, isn’t it? And maybe that’s the real point of the title, Silence. We are not required to believe that it was the actual voice of Jesus telling Father Rodriguez to apostatize. It was only his own anguished feelings of compassion and guilt masquerading as the mythical Jesus of first century Palestine. Because, of course, it’s now pretty safe to assume, at least in the circles Mr Scorsese moves in, that that’s all Jesus ever was in the first place: the inward voice of the Christian conscience which is ordinarily almost as silent as the historical Jesus, assuming he ever existed.

|

The point is made earlier in the movie by a bit of business with an icon of the suffering face of the crucified Christ, remembered in his agony by Father Rodrigues and identified with his own face for the movie audience. In the end, he must also come to see himself in the film’s Judas figure, one Kichijiro (Yôsuke Kubozuka), who keeps betraying his fellow Christians, beginning with his own family, who are all killed as a result, and extending to Fr. Rodrigues himself, but who nevertheless keeps asking for absolution in the hope that “God will take me back.” When he asks: “Where is the place for a weak man in a world like this?” Kichijiro becomes, in effect, the central figure of the film, the mentor in weakness to the priest whose faith, he comes to believe, requires him to identify himself with the weakest and most wretched of mankind by saving their skins as well as his own.

If you were asking yourself (as you probably haven’t been doing) what it would take to make the Catholic Church once again palatable to the great and good of the media consensus of today, here is your answer: a politically chastened, if not (yet) quite politically correct Catholicism which has learned through bitter suffering and guilt not to insist on being Catholic but, rather, to open itself up to other religions and other cultures. For it’s not, after all, the faith itself which is to blame for the excesses of the Catholic Church, assuming for the sake of argument that such excesses exist, nor even its superstitions. It’s the stubborn, selfish and self-righteous insistence on sainthood, also known as the conceit by which some people are encouraged to think themselves better than others.

That is what we of the post-Christian era can’t abide. That is what gets in the way of Jesus’s command, real or imaginary, to become like the least of these, my brethren. Such an idea might have got Mr Scorsese burnt at the stake 400 years ago, but now he has less to fear from it even than he did from the short-lived backlash to The Last Temptation of Christ. So far as I know there has been no backlash to Silence. I suppose that even many believers, nowadays, find it one of the consolations of their new, revised version of the faith to think that so little is required of them.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.