Confederate statues honor soldiers’ valor, not beliefs

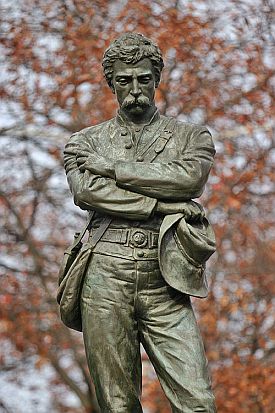

A few blocks from where I live in Alexandria, Va., at the intersection of Prince and Washington Streets, there stands a bronze statue — fully worthy of President Trump’s epithet “beautiful” — of a young man, his head bowed, his arms folded across his chest and a broad-brimmed hat in one hand. A canteen and an ammunition bag slung around one shoulder and hanging by his side is the only indication of his military career. He is facing south.

On the marble south face of the plinth, you may read: ERECTED TO THE MEMORY OF THE CONFEDERATE DEAD OF ALEXANDRIA VA BY THEIR SURVIVING COMRADES, MAY 24TH 1889, and on the east and west facing sides are carved the names of the dead. On the north side appear the words: “They died in the consciousness of duty faithfully performed.”

The statue, by the Czech-American sculptor Caspar Buberl (1834-1899), who also created many memorials to the Union dead as well as the monumental frieze on the Pensions Building (now the National Building Museum) in Washington, is titled “Appomattox,” the site of the Confederate surrender that ended the Civil War. By his title, as by his attitude, the statue symbolizes defeat. It has nothing at all to say about race.

That the nameless young man has remained for more than 125 years at the center of a town now acknowledged by everyone as belonging irrevocably to the country he fought against also makes him, like many if not all of the statues now commemorating those who fought in that war, a symbol of reconciliation between the two halves of the recently-divided nation. The passions that had divided it were seen as having been buried along with those who had died because of them.

It is not surprising, then, that those who see political advantage to themselves from reopening those old wounds to try to re-divide the country would attack the statues first and, with them, the rights of the defeated to remember. For what they remember is not just the dead but that old-fashioned concept, now nearly as dead as they are, of “duty faithfully performed.”

They may also remember another word even more outmoded than duty. “Honor,” was something well understood on both sides of the Civil War as what distinguished that struggle from the kind of mob violence perpetrated in Charlottesville, Va., last weekend. Honor has gone out of fashion partly because it was something owed to the enemy as much as to oneself. It would have been a shame and a dishonor to an honorable man of that era claiming, in the words of Douglas MacArthur, our last true 19th century general, “to do his duty as God gave him the light to see that duty” not to have allowed a similar claim on behalf of an honorable enemy.

If the two sides in the Civil War had not had this understanding of honor in common, and the corresponding respect for those who saw their duty in diametrically-opposite terms, the country could never have come together again after Appomattox to have become, only a generation later, the world power it is today. Nor without the malice-towards-none reconciliation symbolized by “Appomattox” could it have overcome the legacy of slavery to the extent it has 150 years later.

Alexandria also happens to be the hometown of Robert E. Lee, whose statue’s removal at Charlottesville precipitated the demonstration which precipitated the violence there last weekend. The city council voted last September to move Caspar Buberl’s statue to another location, though enabling legislation in the General Assembly to allow them to do so has so far not been forthcoming.

It is understandable why the descendants of black slaves should regard the idea of a statue commemorating the Confederate dead as a monument to hate. But if they look at “Appomattox” they may be able to see that there is no trace of hate in it — not in the defeated soldier mourning his lost comrades nor in the words which honor them. There is only the love which, as He who enjoined us to love our enemies said, no man hath greater than: that he lay down his life for his friend.

If we cease to honor that sacrifice, we cease to honor our re-united country — which is exactly what many of the new iconoclasts intend.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.