Revolutionism redux, part II

From The New CriterionWay back in January, 2018, The New York Times marked the first anniversary of President Trump’s inauguration by publishing (under the amusing headline: “Vision, Chutzpah and Some Testosterone”) a selection of letters from supporters of the President with the following rationale:

The Times editorial board has been sharply critical of the Trump presidency, on grounds of policy and personal conduct. Not all readers have been persuaded. In the spirit of open debate, and in hopes of helping readers who agree with us better understand the views of those who don’t, we wanted to let Mr. Trump’s supporters make their best case for him as the first year of his presidency approaches its close.

Such fair-mindedness had its limits, however. As if the editors were afraid that even this tiny island of pro-Trumpery in the vast media sea of anti-Trump vitriol might drive their readers to their fainting couches, on the following day they also published letters from disillusioned Trump supporters and from readers reacting negatively to the pro-Trump correspondents, the latter under the heading: “The Furor Over a Forum for Trump Fans.”

Furor it was, too. One of these furious letters asked if the paper was also offering the hospitality of its columns to the Flat-Earth Society. Another, similarly outraged and fairly dripping with contempt, asked: “Why do you keep asking questions of Trump voters? Who cares what they think?” Obviously, even at that point, few cared who were still bothering to read The New York Times. But perhaps the most salient response, and certainly the most poignant, was also the shortest. “Dear New York Times,” wrote Robyn Lipman of New York, speaking for all her many Trump-hating brethren, “please don’t ever do that again.”

I don’t think you have to worry, Robyn. Whether from you or from someone else, the Times has received the message loud and clear. I suspect they had a pretty good idea of it before they ever sought out a few Trump voters for an alternative view, and that they only printed the result in order to demonstrate, with the help of people like Robyn Lipman, that their otherwise uniformly anti-Trump coverage was only what readers were demanding. “What can we do?” the editorial board seemed to be asking. “The influx of new digital subscribers that make up the ‘Trump bump,’ which has saved us from the fate of so many lesser newspapers, want nothing but partisan attack, and they want it hot. See? You on-the-one-hand-on-the-other-hand, fair-minded types who still assume the good faith of those you disagree with are living in the past. Welcome to the new media world.”

It’s a plausible argument and one that others are making more explicitly on the paper’s behalf. Matt Continetti of the Washington Free Beacon, reviewing Jill Abramson’s book Merchants of Truth in The Claremont Review, wrote:

If readers are not particularly interested in reporting, then money-losing publications have two choices. One is patronage, i.e., find a rich donor. Another is somehow to monetize the prestige associated with certain titles. . . Subscribe to the New York Times and you can help resist Donald Trump. People will pay for status, though not very much. And status is elusive. Only a few brands can offer it.

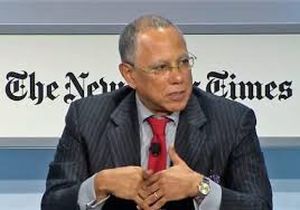

|

| Dean Baquet |

Holman Jenkins of The Wall Street Journal further generalized the Times’s experience to that of newspapers in general, desperate to make up for the loss of advertising revenue to the Internet. “It’s readers nowadays who pressure newspapers to toe a line,” he wrote. “Publishers pine for the era when advertising dollars insulated us from such pressures.”

The occasion for Mr Jenkins’s column was a closed-door “Town Hall” meeting of the New York Times staff presided over by the executive editor, Dean Baquet, a recording of which was leaked to Slate and a transcript published there in mid-August. The meeting was called after the Times newsroom was thrown into a tizzy over a headline — “Trump Urges Unity Vs. Racism” — which, though strictly factual, was deemed insufficiently anti-Trump and was accordingly changed to: “Assailing Hate But Not Guns.”

Reading the transcript, I thought it pretty clear that what was offensive about the original headline — a least it was the point Mr Baquet was most concerned to address — was that it stepped on the new “narrative” about President Trump, even then in the process of being wheeled out by the Times editors after their disappointment with Robert Mueller’s testimony to Congress in July. This was the new-old story of Mr Trump’s supposed racism or, better, his “white supremacism” — both treated as being as much matters of indisputable fact as the Russian collusion had been before them. Here’s how Dean Baquet put it:

Chapter 1 of the story of Donald Trump, not only for our newsroom but, frankly, for our readers, was: Did Donald Trump have untoward relationships with the Russians, and was there obstruction of justice? That was a really hard story, by the way, let’s not forget that. We set ourselves up to cover that story. I’m going to say it. We won two Pulitzer Prizes covering that story. And I think we covered that story better than anybody else. The day Bob Mueller walked off that witness stand, two things happened. Our readers who want Donald Trump to go away suddenly thought, “Holy s***, Bob Mueller is not going to do it.” And Donald Trump got a little emboldened politically, I think. Because, you know, for obvious reasons. And I think that the story changed. [emphasis added]

I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that the recording was leaked on purpose. Not only was Mr Baquet, in this allegedly confidential setting, keeping up the public pretense that the “hard story” the Times covered “better than anybody else” was a story at all and not, as the world now knows, a complete non-story, but he also made Holman Jenkins’s point for him: that the Times editors are the prisoners of their readers’ hatred for Mr Trump and eagerness to read anything to his detriment. Some of the “staffers” present at the meeting made the same point. As one of them put it:

I’m wondering what is the overall strategy here for getting us through this administration and the way we cover it. Because I think one of the reasons people have such a problem with a headline like this — or some things that the New York Times reports on — is because they care so much. And they depend on the New York Times. They are depending on us to keep kicking down the doors and getting through, because they need that right now. It’s a very scary time.

Which is to say that, at least in their own minds, these people have turned a once-great news organization into a vehicle for anti-Trump propaganda for the sake of the readers who depend on getting their fix of Trump-hatred every day.

But look at that word “frankly” in the quotation from Dean Baquet. As so often, it is used for misdirection, or so it seems to me. In other words, the frankness comes before it, not after: it is really these newsroom “staffers” themselves and not the readers for whose sake the constant drum-beat of Russian “collusion” was kept up for two and a half years. For their sake, too, the focus was now shifting and, “collusion” having failed to dislodge the President, the “story changed” to racism. The new narrative was to be led by the paper’s “1619 Project,” launched in the following Sunday’s New York Times Magazine, the point of which, according to Mr Baquet, was “to try to understand the forces that led to the election of Donald Trump.”

Behind the euphemisms and the therapeutic jargon, he was signaling to his rebellious staff members that the old journalistic variety of scandal-mongering — whereby you try to find something illegal, immoral or simply embarrassing in your target’s past — had been tried on President Trump and had failed. Naturally he didn’t mention that it failed because it was founded on a fiction. That didn’t matter anyway. The point was that the paper had given the old-timers, those Watergate-era romantics, their chance to do it again, and they couldn’t. So now we move on to the newer kind of scandal hunt based on “racism.” This makes the revolutionaries’ work much easier, since the target doesn’t have to have done anything wrong or even embarrassing. “Racism” (or any other of the new cardinal sins by intersectionality) may be merely imputed based on almost anything you like, including — as intimated by the 1619 project — the very existence of a country in which slavery had once been permitted.

Now it may be that Dean Baquet really believes that the advent of slavery in what was to become, over a century and a half later, the United States, was among “the forces that led to the election of Donald Trump,” but I beg leave to doubt it. The muted cynicism of his whole performance here suggests that he is simply offering the Young Turks of the newsroom a new propaganda line to pursue as an apology for the failure of the old one. As I noticed in these pages some months ago (see “Geography Lessons” in The New Criterion of February, 2019), Jill Abramson in the book under review by Mr Continetti had already suggested that those who were driving the Times’s propaganda effort were (according to Howard Kurtz) “younger staffers, many of them in digital jobs” who were pressuring the higher-ups. “The more ‘woke’ staff thought that urgent times called for urgent measures,” claimed Ms Abramson; “the dangers of Trump’s presidency obviated the old standards.”

This is also the general impression created by the transcript of the meeting — in which, for example, Staffer A asks:

It appears to be that the public narrative around the headline is different from the internal narrative that I’ve been hearing. So for example, I know that the copy desk thing was a slip. But I have also heard that someone actually raised concerns about the headline and was overruled. So, I’m just trying to reconcile what I’m hearing from my co-workers internally and what I’m hearing from my other co-workers in the public.

Then, when Dean Baquet explains that the internal objection before the external (Twitter) objections was more on the grounds of the story itself as leading the paper than about the headline, Staffer B pipes up:

I just kind of wanted to return to the internal debate before the headline went to print. Do you think there was a breakdown there other than space pressure or time pressure? And if so, I wonder what you think that that breakdown was?

Then there is more back and forth on the genesis of the offensive headline in what is called the “print hub” before Mr Baquet calls on Tom Jolly, who runs the print hub. Tom Jolly tries to calm the troubled waters by suggesting that what is needed is better coordination over the “storyline” — here a euphemism for the anti-Trump narrative — between the headline writing editors and journalists submitting their stories. Then Mr Baquet intervenes again to assure the staffers that

I talked to the editor who wrote the headline. He’s sick, you know. I mean he feels terrible. He feels more terrible than he should, to be frank. But it feels terrible, and I don’t want to walk away from this with all of us thinking that they’re a group of fumble fingers on another floor of the New York Times secretly f***ing up the New York Times. They’re not.

That’s all very well, says Staffer C, but. . .

When it came to actually changing that headline, how much influence did the reader input have? I mean, OK, all you guys didn’t like it. You were unhappy. But was a change in the works, or was it the response?

Oh, yes, yes, yes. On that point, the executive editor is emphatic: “We were all — it was a f***ing mess — we were all over the headline.”

Now whether the “reader input,” as he suggests, was anticipated by the editors themselves or not, it seems pretty clear to me from this exchange that the staff input was. And that Mr Baquet and the other powers that be at the Times were terrified of it. What we are hearing here sounds like nothing so much as an impromptu revolutionary tribunal made up of those young, “woke” staff members mentioned by Jill Abramson, nosing out the source of a thought-crime committed by one of their nominal bosses — someone of whom the very least that could be expected was that he should be “sick” and feel “terrible,” times three, about his egregious error. Mr Baquet’s refusal to name him can only be an attempt to shield him from a fate at least equally “terrible” at the hands of the newsroom’s Comité de salut public.

Which is to say that the “forces” (to use Mr Baquet’s word) at work here are at least proto-revolutionary. They are the same forces which are driving the Democratic presidential candidates toward the hard left and which are also behind the Business Roundtable’s embrace of political correctness and thus of the “climate science” intended to put many of them out of business — behind, too, Nike’s Colin Kaepernick-inspired anti-Americanism and Gillette’s scolding their customers for “toxic masculinity” and American auto-makers’ rejection of regulatory relief from the Trump administration. They are also, I think, what make judges, once a by-word for sobriety, kowtow to the latest absurdities of the “transgender” lobby.

The Barton Swaim thesis, mentioned in this space last month, that Democrats have taken what they regard as the extremism of the Trump presidency as a permission to indulge their own extremists, presupposes that top-level Democrats have always been secret radicals and revolutionaries and have just been seeking an excuse to break cover — an excuse they imagine they have found in popular revulsion against President Trump. This idea certainly fits in with a common conservative view of the party and of progressivism generally as a stalking horse for socialism or worse. I’m not so sure. Someone like Dean Baquet is himself a Mueller-like figure, ironically enough: the respectable face of the anti-Trump “resistance” in the media, as Mr Mueller was for the Justice Department, but who is really only a figurehead for the zealots behind and beneath him urging ever more hostile pursuit of the President.

This is a revolutionary dynamic: if you don’t want to become a victim of the revolution, you had better become a proponent, and the more zealous a proponent you can be the better — which is to say the less likely you are to be purged when what has been made to look like the surging tide of popular outrage breaks over you. It is also the dynamic of the political polarization for which the left of the left is principally responsible through its moralization of political differences, and it naturally contains within itself an unwillingness to make any concessions to those whom too many have taught themselves to think of as enemies. It’s the pas d’ennemi à gauche phenomenon familiar from the Popular Front of the 1930s, and its revolutionary purposes are increasingly evident far beyond the newsroom of The New York Times where, as is now clear, no skepticism about those purposes is any more likely to appear than is another readers’ forum of praise for President Trump.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.