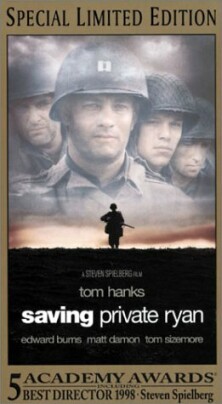

Saving Private Ryan

It’s time that the team of computer programmers from IBM who developed “Deep

Blue,” the machine that beat the world chess champion, Gary Kasparov, to take on

a real challenge. Let them try to develop a movie-making program that is more

formidable — or more machine-like — than Steven Spielberg. His latest

directorial effort, Saving Private Ryan, is as usual a brilliant

demonstration of movie-making. At the level of the individual shot it is just

about perfect. Also as usual, the film considered as a dramatic whole is utter

nonsense. Fortunately, not much thought is involved in it. For it is when the

unbeatable movie-making machine has to think that it starts to whirr and pop and

smoke until finally it shuts down altogether.

The mystery about Mr. Spielberg, and the reason why he seems so machine-like,

lies in the answer to the question of why he goes on making movies — since,

apart from the fact that he is programmed to do so, there seems no point to any

of them. The nearest he comes to identifying the rationale of Saving Private

Ryan, which deals with a rescue mission aimed at finding and retrieving an

American paratrooper in Normandy who is now the sole survivor of four brothers,

comes when the gruff, no-nonsense Sergeant Horvath (Tom Sizemore) says that, in

later years when they look back on their part in the war, Ryan’s rescuers will

think that “Maybe saving Private Ryan was the one decent thing we managed to

pull out of this whole godawful mess.” So much for having defeated Hitler’s

dream of world conquest!

Such a line in context is even more ridiculous, because the film itself does

such a good job of presenting to us the human cost of the war. We must suppose

that it was all for something even before the brass decided that Ryan

(Matt Damon) should be sent home to his mommy. There are some serious moral and

philosophical problems raised by the mission, to be sure. Can it be justified to

take away some of the vital troops necessary to the larger purpose of winning

the war for the sake of a bereaved mother in Iowa? But Spielberg pretty much

ignores such questions after the scene in which General Marshall (Harve

Presnell) rules in favor of the rescue. Instead he has his hero and the leader

of the rescue mission, Captain John Miller (Tom Hanks), talking about having to

square his conscience by reckoning that for each man under him who is killed

ten, or twenty or thirty others will be saved.

This too is obvious nonsense. No one goes to war to save lives (rather,

because some things are more precious than life), and it is a catastrophic

misstep for Spielberg to put such words in Miller’s mouth — a failure of

imagination as total as the successes he has enjoyed in so many of the movie’s

details. How could he make such a mistake? Because, I think, accounting for his

characters’ actions is for him just another trick of the trade. He himself has

no views one way or the other on why men go to war. It has probably never even

occurred to him that it is an interesting question, philosophically. He just

retrieves a bit of superficially plausible dialogue to cover the hole from his

capacious, fully-searchable data base of movie-making methods and

techniques.

Which is not to say that most of these techniques do not work impressively

well. Perhaps the most impressive comes with his portrayal in the film’s

opening passage of the landing at Omaha beach as seen by Miller and his men. Of

course there is lots of blood and body parts being blown off before our eyes,

the quick-cutting confusion of battle and the fear on the faces of the men.

Those are given. But what makes it special are the little Spielbergian touches

which extend beyond the visible to the audible — the variation between

defeaning noise outside and its muted quality in underwater shots, for example.

For a moment we are presented with the possibility of sanctuary from the

murderous machine-gun fire on the beach — only to see it snatched away again

in a moment as men are being shot and blood spurting from them even under

water.

More variation in sound comes with scenes purporting to represent the

numbness inside the head of Miller, where the immediacy of battle and the

imminence of sudden and violent death suddenly both seem a long way away. We

have the sense of a momentary and irrelevant refusal by the body to respond to

such overwhelming stimuli, and we switch back and forth between Miller’s point

of view and that of the omniscient and indifferent god of battle who accepts all

the sacrifices without a single moment of human sympathy. One is aware, as one

would hardly be if one were actually there, of the constant jingle of the brass

bullet casings as they are ejected by machine guns, and, paradoxically, the

sound makes us feel as if we are there. As the fierce struggle for the

beachhead dies down, the camera pulls back to show us one of the three dead

Ryans lying face down in the sand — in the midst of half a dozen dead fish.

The fish are another nice, Spielbergian moment.

One could go on. There is scarcely a scene in the entire two hours and forty

minutes that does not yield its riches — to the point where one becomes

vaguely aware of and annoyed by such effortless mastery of cinematic

illusionism. Oh yes, we think during a shot in which rain falling on leaves is

mixed up with and finally gives way to the patter of rifle fire, here is yet

another excellent bit of movie-making. But the fact that we are thinking of it

as movie-making makes the trick somewhat counterproductive. Thus we are more

than usually alert when Miller announces to one James Ryan that his brothers are

dead. This, we realize, cannot be what it seems to be. Ryan weeps. Miller’s

squad of battle-hardened veterans, including those most skeptical about the

mission, look on and seem if only for a moment to feel sympathy. Of course it is

the wrong James Ryan. This Ryan’s brothers are boys still in grammar school. The

men turn away to resume their search, and Ryan calls to Miller: “Does this mean

my brothers are OK?”

It is yet another touch of the Spielbergian magic. But when the magic becomes

too profuse and too predictable — and when it comes without any persuasive

dramatic context — we must withhold from it the accolades that would be

accorded to half as much skill shown by those who are better dramatists, if much

lesser masters of filmic technique.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.