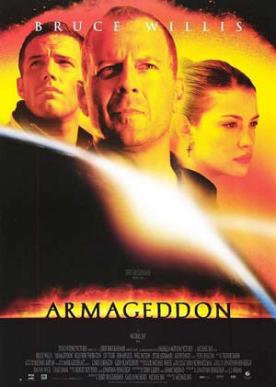

Armageddon

There are several things to like in Armageddon, directed by Michael Bay. One is that the sympathetic main character, Harry Stamper (Bruce Willis), is a wildcat oil-driller who is introduced to us as he harasses a Greenpeace ship which has been sent to harass his offshore drilling platform by hitting golf balls at it. The next thing we know he is chasing a young man called A.J. (Ben Affleck) around the rig with a shotgun after catching him in bed with his daughter, Grace (Liv Tyler). As A.J. is his right-hand man he tells him he doesn’t want to kill him; he just wants to shoot a foot off. Good thing he’s not his right-foot man. “You can still work with one foot,” Harry tells him. Young Grace, wise beyond her years, prevents her father from maiming her boyfriend and criticizes him (the father) for being “handicapped by a lack of maturity.”

This is actually true, though we haven’t seen the evidence of it yet. It seems a moderate and condign measure to bean environmentalist wackos with golf balls and it is, if anything, rather underpricing it to put the value of your daughter’s virtue at one foot. The real immaturity shows when, because Harry is “the best deep-core driller on earth,” he and his roughneck crew are shot into space and deposited on the “global killer” asteroid chunk hurtling towards good old Earth. There they are supposed to dig a very deep hole, deposit an H-bomb and (if NASA’s calculations are right) blow it into two pieces which will fly off in other directions. “The US Government just asked us to save the world,” Harry tells the guys. “Anybody want to say no?” Nobody does, but they do want to make a few requests: for fixed parking tickets, for instance, bringing back 8-track tapes, and never having to pay any taxes again. Ever.

These are obviously guys whose hearts are in the right place. Their immaturity is actually that of their creators and lies in their indiscipline. The film flatters the teenage delusion that the guys who follow the rules are dull and humorless losers while the guys who break them are not only romantic and free and cool but also the ones who are successful, even in highly delicate operations calling for precision and rationality. Here, not only the political command structure trying to deal with the crisis but the Air Force and NASA (bar a few free spirits) are corrupt, cowardly and, above all, stupid, while it is the hell-raising wildcatters who are held up for our admiration and emulation.

You can understand such a celebration of indiscipline not only because the film is directed (as nearly all American movies are these days) at a 12 year-old mentality but also because the filmmakers themselves suffer from a similar infirmity in their inability to say no to explosions. Much of the movie consists of quick cuts from one bit of smashing machinery to the next while the thread of the narrative is forgotten as unimportant. The essence of the picture is blowing stuff up, without quite killing all the heroes. So they do it again and again without bothering too much about explaining the processes to us, or why things are blowing up. This becomes boring after a while, especially as we already know the outcome. As so often at the movies these days, one wishes that someone would learn the virtues of understatement. When it comes to blowing things up, more is less. But the people who run things in Tinseltown are like trailer trash that has just won the lottery and proceeded to fill the trailer with gaudy junk.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.