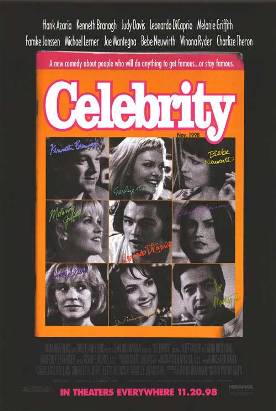

Celebrity

Celebrity is the first good film Woody Allen has made since Husbands and Wives, though it’s still not all that great. It is about celebrity, which is a subject of major concern to the postmodernist sensibility, and it makes use of a central postmodern joke. That is, the celebrity director known as “Woody Allen,” does not actually appear as an actor and alter ego in this film by Woody Allen, as he does in so many of his films. It is one reason why it is his best in years. But he has put in a surrogate Woody, played by (of all people) the British actor, Kenneth Branagh. Branagh, as a journalist called Lee Simon, does the Woody impersonation to a T, and everyone recognizes who he is supposed to be—a fact which makes its own ironic commentary on the matter of celebrity.

But the heart of the film lies in a remark made by Robin (Judy Davis), Simon’s ex-wife, when she goes from being a schoolteacher, teaching Chaucer, to being a TV star, promoted by her new boyfriend, Tony (Joe Mantegna), with a trashy show about the rich and famous in New York She was, she says, “performing a serious function” as a teacher. She has now left off doing that and instead has “become the kind of woman I have always hated. And I’m happier.” It is just convincing enough to make us pause for a moment. Quite probably, Woody Allen himself is a divided character like this, loathing the whole celebrity machine of which he himself is obviously a part, but at the same time loving it—and hating himself for loving it.

But happiness? We don’t believe for a single moment that Judy Davis’s character is happy, any more than we believe that the character developed for himself over a score of movies by Woody Allen is. The comparative “happier” deliberately leads us astray. If all life is meaningless, then it is simply marginally better to get through it with the help of the deference paid to fame. That is all. Robin, interestingly, had never particularly wanted to be happy and is, in fact, terrified by the idea. When in one of the movie’s several funny scenes she goes to see a prostitute (Bebe Neuwirth) for instructions in how to give her new man, Tony, pleasure in bed, the latter asks: “What goes through your mind when you’re doing it?”

“The Crucifixion.”

That’s a little over the top, maybe, not just in tastelessness but in its attempt to conflate Allenesque nihilism and Roman Catholic guilt. But the movie is more successful on its most familiar ground, as Lee is presented as that cliché figure, the middle-aged man afraid that “happiness” has passed him by. We see him in a flashback at his high school class reunion, where the “mid-life crisis” happens before our eyes. After 16 years of marriage, “I’ve got to change my life before it’s too late,” he says to a classmate psychiatrist. “I’m married to a schoolteacher, writing the occasional travel piece, never knowing what it’s like to make love to that f***ing sleazy blonde that’s with Monroe Gordon,” a minor celebrity as lounge singer in nearby hotel restaurants. Thereafter he plunges into a life as a swinging bachelor and hanger-on to the stars.

Celebrity thus stands for all the meretricious allure of “happiness”—which in the end we are assured by Robin is nothing more than luck. It is the moral of the story. She has found a wonderful guy in Tony, who marries her, even though she is so full of a kind of “guilt” at the idea of being happy (because of Catholic upbringing) that she leaves him at the altar at the first attempt. “No matter what the shrinks or the self-help books say, when it comes to love, it’s luck,” she says. Meanwhile, Lee’s life with his latest hot young girlfriend, Nola (Winona Ryder), which had seemed like pure Kismet, is a nightmare.

As in all the best of Woody Allen’s movies, however, this central, nihilistic thread can be disregarded and you can just laugh at the jokes that hang loosely off it. One of the best has to do with an appearance by Leonardo Di Caprio as, like the real Leonardo Di Caprio, the superstar of the pre-teens but a much nastier piece of work. At the culmination of this episode, Lee finds himself engaged in group sex while trying to pitch his screenplay—about an armored car heist but with “a very strong personal subplot”—to the young star next to him in the bed. Not surprisingly, he finds himself unable to perform with the airhead groupie who has fallen to his lot and is forced to fall back on small-talk. She asks him what he does. He says he’s a writer. “I’m a writer!” she says brightly. “You ever hear of Chekhov?”

“Yesss,” says Lee.

“I write like him.”

Almost equally hilarious is a scene set in the green room at Tony’s daytime TV show when Robin has mixed up the booking dates. skinheads, Nazis, Klansmen, Jews, blacks all mix on easy and friendly terms as all prepare to do the only thing they really care about, which is to appear on television and so stake their own small claims to celebrity. We see a rabbi elbowing his way to the buffet and calling out, “Did the skinheads eat all the bagels already.” It is the final word on the subject of celebrity— not very original, perhaps, but still funny.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.