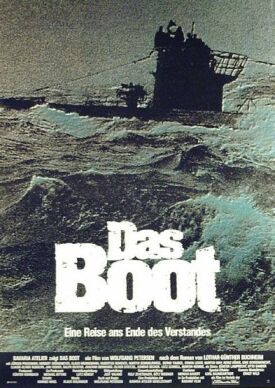

Boot, Das (The Boat)

The version of Wolfgang Petersen’s classic Das Boot now arriving in your neighborhood multiplexes is a new director’s cut of the version of 1982 which adds over an hour of original footage to bring the film to an epic three and a half hours in length. The time flies. This is perhaps the best war movie ever made, capturing as it does both the excitement, the adventure and the glory of war on the one hand and the terror and horror of it on the other. The press material and other reviewers naturally stress the “anti-war” angle—especially as it is about the valiant submariners of Nazi Germany, but don’t you believe it. To be “anti-war” it would have to be ideological and doctrinaire and preachy and, well, bad, and it is none of these things. It represents indifferently the good and the bad of war and is neither pro nor anti—which of course is just what is necessary for any film about war to be convincing.

Film begins in a French nightclub during a drunken bacchanalia. The ordinary sailors make rude gestures, insult and even urinate on their officers as the latter make their way by car to the club. No one thinks too much about it. As they put to sea from the submarine pens at La Rochelle the next day, discipline is restored, though the wily old Captain of U-96 (Jügen Prochnow) is full of forboding about the youth and greenness of his crew. He asks the young war correspondent who is travelling with them, Lt. Werner (Herbert Grönemeyer) not to snap pictures of them now, because it would shame the British to see that the people sinking their ships are mere beardless boys, who should still be at their mothers’ breasts. They make him feel old, the captain confides. He feels as if he is leading a children’s crusade.

The atmosphere on board is one of anti-heroism and admiration for the British. The captain especially ridicules the propaganda line that Churchill is a drunk and paralytic. It is late in the war, the convoys are mostly getting through and Churchill is doing pretty well for a drunk and a paralytic. The one gung ho officer still talks about bringing him to his knees, but the captain dismisses him with annoyance: they are nowhere near bringing Churchill to his knees. Nazi pieties are tolerated, but Göring is called a fat slob and battle weary men enjoy pulling the chains of the gung ho officer and the naïve war correspondent by singing “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary”—in English—together. Likewise, when Liszt’s “Les Préludes,” Hitler’s chosen theme music for Operation Barbarossa, comes on the radio the Chief Engineer (Klaus Wenneman) sharply orders that it be turned off.

Yet the theme music associated with the thrilling shots by Jost Vacano, the director of photography, of the U-Boat making speed through the Atlantic swell has a similar rising, thrusting, heroic sound to it. I take this to be Petersen’s ironic commentary on the glory of war as it arises out of the horror. The film is full of this kind of alertness to paradox and ambiguity, which is what makes it such an exciting experience. At one point when the sub torpedoes an allied tanker and another ship in a convoy, the can hear on their sonar the sounds of one ship going down. “Their bulkheads are breaking! They’re drowning!” shouts one sailor. Then the camera pans around the faces of the others to show the same mixture of triumph and regret. They know it could be them drowning next. And, indeed, they are depth-charged to within an inch of their lives. “Pigs! Rotten pigs!” says one sailor as they are shaken almost to pieces. To buck them up the Captain says: “Boy, we really gave it to them when those bulkheads started breaking. . .”

Another paradox comes when they go back to the scene of their torpedoings and find that the tanker is still afloat and burning. They shoot another torpedo to sink her and only then realize that there are still men on board. “Why weren’t they rescued?” says the Captain indignantly. “All these hours!” But when the men start swimming toward them for rescue, he pulls back out of reach. War is full of such moments which combine pity and savagery and so is this marvelous film. In the passage which probably most critics are thinking of when they call it “anti-war” it is one of several occasions when all looks hopeless for the sub. Poor idealistic Werner talks of his romantic illusions of going forth to meet “the inexorable, where no mother will look after us, no woman will cross our path and where only reality reigns with cruelty and grandeur,” he says, quoting his own fine words about the warrior’s life. Now, he says bitterly: “I was drunk with these words.” He weeps. “Well, this is reality.”

Except it’s not. The chief finally does get everything fixed. They blow their tanks full of compressed air, pop to the surface like a cork and head back to La Rochelle with the captain marveling: “All you need is good people. Good people.” And that’s what he’s got. It is not the end, and they do not all return, in Shakespeare’s Cleopatra’s words, “from the world’s great snare uncaught.” But for the moment all that matters is the Captain’s exhilaration as, speculating that the enemy doesn’t pursue them because he is celebrating their sinking ashore, he shouts into the wind from the bridge, “Not yet, Kamaraden! Not yet!”

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.