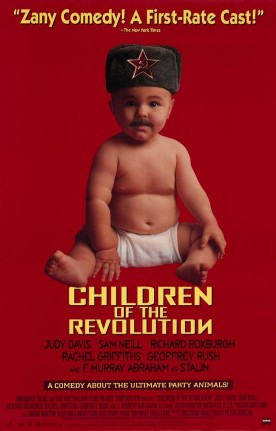

Children of the Revolution

Children of the Revolution, written and directed by Peter Duncan, represents the less attractive side of the Australian sensibility I have so often had occasion to praise here. For it is a too-natural development out of healthy skepticism to turn merely cynical, and that is what, I take it, we have here. There is, to be sure, a certain amount of affection for poor old Joan (Judy Davis), who is so besotted with Soviet Communism that she goes to Moscow, goes to bed with Stalin (F. Murray Abraham) and, in effect, kills him with the subsequent exertion he is called upon to make. It is a cute idea, too, to show the bloodthirsty dictator cosying up to her like a teenage boy at the movies, and even to show Malenkov, Beria and Khruschev appearing at her door in the morning with bouquets of flowers. “How can they be so happy?” she asks her new friend, the Australian double agent David Hoyle, aka “Nine” (Sam Neill).

I even like the fact that Nine is not sure himself which side he’s really working for but that he doesn’t much care because the Russians don’t much care either. Australia just doesn’t matter enough. When he tells Joan that he has orders from the Australians to kill her and from the Russians to protect her, she (not unreasonably) asks what he proposes to do. “Frankly, Joan, it’s a bit of a tangle.” But after Stalin’s death he manages things very efficiently for her journey home.

“It’s all right. You’ll be safe. The Russians will tell the British who will tell the Australians that you’re a mole for MI6.” “Thank you,” she says.

But the joke will not bear all the weight that’s being put on it here, and the satire or humor or whatever it is lumbers heavily through the story of the life of Stalin’s illegitimate son, Joe (Richard Roxburgh), who discovers early on in life a fascination for prisons and handcuffs and later makes a name for himself as leader of the Prison Guards’ union and the police. “Isn’t the point to help people?” he asks his appalled mother.

“Well, people, yes; not the police!”

The picture, which can’t quite make up its mind between the documentary style and straightforward narrative, makes its point in an yet another style, a fantasy interview between young Joe and his father, where young Joe in his bluff Aussie style dismisses the old man’s cant about wanting to do the best for his people and presses him uncomfortably on how it was that he came to be a monster. “I don’t know,” Stalin is finally forced to admit. He also memorably punctures his mother’s dreams of revolution by telling her that if she thinks the Australians are going to shake the sand off their beach towels, put their berets on and storm the opera house, she’s either stupid or mad. And he knows she’s not stupid.

It is good to see error exposed, but only if truth is put in its place. Here Duncan has nothing to put in its place. There is a brief spurt of interest as we see poor old Joan watching the collapse of Communism on television and being driven to distraction by that “walking birthmark,”

Mikhail Gorbachev. The real capstone for her is the idea of a McDonalds in Red Square. It is the end of civilization as we know it. “The devil doesn’t carry a gun,” she rails to her long suffering husband, played by the always-excellent Geoffrey Rush; “the devil carries fast food, cheap appliances and bad television.” But the film ends with a final plunge into cynicism and some dull and predictable satirical barbs directed at the celebrity culture of the media. By this time not even Rush, nor Judy Davis’s terrific portrait of Joan, by far the best thing about the picture, has been able to inspire us with anything but relief at seeing the back of these tiresome characters.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.