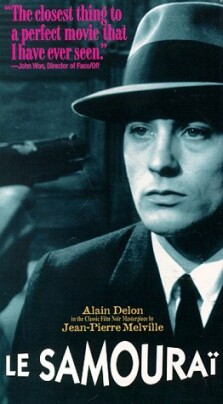

Samourai, Le

If John Woo thinks, as the publicity material claims, that Jean-Pierre

Melville’s Le Samourai is

“the closest thing to a perfect movie

that I have ever seen” I wonder why he

does not make movies like it himself? In fact, Le Samourai, made in 1967

but only seen in this country before in the wake of The Godfather, in a

badly cut and dubbed version called

“The

Godson,” is at the opposite extreme

from a John Woo movie. Self-consciously noir it is a minimalist thriller

in which the two or three moments of action are extremely brief, almost

invisible, while the rest of the film is a slow paced cat-and-mouse game, shot

largely without dialogue, in wide shots and long takes, between a hired killer,

Jef Costello (Alain Delon) and his police pursuer (François Perier).

It is very watchable nonetheless. We see Jef setting up an elaborate alibi

without knowing that that is what he is doing, and then admire how the alibi

holds up when the police bring him in for questioning. But some doubts remain.

Why does he seem to go out of his way to get picked up by going, after the

killing, to an all-night card game? Why not just go home and to bed, since there

is no reason we know of that the police would suspect him? Then, having picked

him up in a trawl with a lot of other men in raincoats, why would they fasten on

him as the suspect, particulary since his alibi seemed airtight? The Inspecteur

says the alibi is “too

perfect” , but it is hard to believe

that a real life cop with (supposedly) 400 men and their stories to sift through

would play a hunch like this.

It is possible to give up such cavils and grant Melville his

donné, but there is still a discontinuity between the tough guy

movie-making, which is often impressive, and the tough-guy criminality it

supposedly represents. To expect more is a form of literalism on my part, given

that tough-guy film-making, especially in France, has always been much more

important than verisimilitude. You just have to sit back and enjoy the visual

treat — Costello’s barely

furnished, shabby room with its high ceiling and two, eye-like windows, the

little bird in a cage whose insistent chirp forms a counterpoint to the

borderline atonal, modernist score, the calm deliberateness with which the

killer does everything, the setting of the brim on his hat as he goes out the

door every time, the methodical way in which he steals a car, both times, the

same model of Citroën. All these things are satisfyingly reassuring to us:

we are tucked up safe inside a genre.

It is really the ending which is the most unsatisfactory thing about the

film. I can’t go into detail without

giving away too much, but I can tell you that it involves the tough guy hit man

having to choose between a mysterious négresse to whom he is

attracted but with whom he has hardly exchanged two dozen words in his life and

breaking a contract, which he has never done. There is a weird kind of

compromise between these two courses of action — a compromise which seems to

have nothing to recommend it but its futility.

C’est magnifique!

C’est also, of

course, absurde. Which is the point. But, were it not for John

Woo’s encomium, I would have said that

it was an ending which only a Frenchman could love.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.