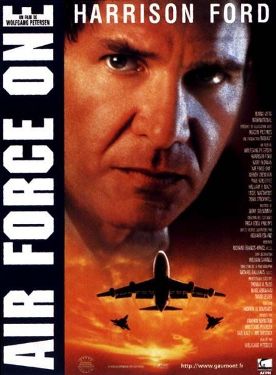

Air Force One

Air Force One by Wolfgang Petersen is a superior example of its kind, the disaster movie cum thriller featuring national security and political issues of a kind that Hollywood invariably gets wrong. This film is no exception. It posits a warlord ruler of Kazakhstan who threatens world peace by turning his desperately poor country into a terrorist state with nuclear weapons. Pretty far-fetched, maybe, but not so far fetched as the idea that one of the President’s Secret Service agents would murder several of his colleagues in order to allow a terrorist gang access to the first family and the president’s staff. Fortunately, Petersen does not attempt to explain why the agent acts in such a monstrously untypical way—something which could only compound the implausibility. It is, therefore, not continuously difficult for us to suspend our disbelief in order to grant the film’s premiss, and the effort is forgotten in the excitement of the action, which is the most that you can expect from a film like this.

Yet it seems that every time we are on the point of forgetting everything but the slick presentation of the cat-and-mouse game between Harrison Ford as President James Marshall and his would-be Russian captor, played by Gary Oldman, somebody says something dumb to remind us of the dumb politics. Near the beginning, for example, Marshall gives a speech in Russian before the Russian leader Petrov, a Yeltsin-like figure, the burden of which is an uplifting call to anti-terrorism. “The dead remember our indifference; the dead remember our silence”—which, of course, is nonsense, as is the president’s self criticism for having acted to stop the terrorist threat “only when our own national interest was threatened.” Now, he resolves that the US must “never again allow political self-interest to deter us from doing what is morally right.”

Shades of Jimmy Carter-style moralism! But this president is supposed to be a tough guy who won the medal of honor and “knows how to fight.” Hence he is able to liberate the presidential airplane from the terrorist gang single-handedly. Yet I wonder if Petersen is not playing with us, just hinting at ironies ( “Nobody does this to the United States; nobody” ) which he then proceeds to bury under an avalanche of patriotic triumphalism. The patriotic tub-thumping sorts oddly with the portrait of “Russian ultra-nationalist radicals,” and Oldman, before he meets a villain’s inevitable end, actually has some rather interesting things to say. He raises the question, for instance, of how his kind of killing is to be morally distinguished from the kind that Marshall does—in a tuxedo, by telephone, with smart bombs.

It is a good question, addressed to the President’s comely 15 year old daughter whose life and virginity rest in the terrorist’s pitiless power. But Petersen has places to go and people to see and makes the little girl answer only: “You’re nothing like my father”—which the bad guy himself seems to consider a sufficient answer, judging by his angry reaction. Curses! Foiled again! Later, he makes another good point when he says to the President himself that “you murdered 100,000 Iraqis to save a nickle on a gallon of gas.” To this there is no answer at all. The Prez is too busy sawing at the duct tape binding his hands behind him with a piece of broken glass he found on the floor when the bad guys pushed him down.

And doesn’t the terrorist have a point, too, when he complains to Marshall that post-Soviet Russia, plagued by “this infection you call ‘freedom’,” has become what is essentially a kleptocracy? “It is you who have given the country to gangsters and prostitutes.” Yeah, well, the leader of the free world is going to let his fists do the talking for him, and a nifty way with a submachine gun. The fact that the terrorists have the best of the arguments while the good guys merely have the superior firepower and a brutish consciousness of their own superior worth suggests a sly post-modern mockery of the patriotic thriller which Petersen has managed to slip in under the radar screen not only of Columbia pictures but of the sort of teenage lunkheads of all ages who go to movies like this. It is my view that you don’t have to be unpatriotic to laugh at such a good joke at the expense of the awful motion-picture industry.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.