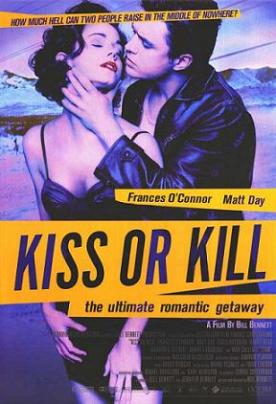

Kiss or Kill

Kiss or Kill was written and directed by Bill Bennett — no, not that Bill Bennett but yet another example of the astonishing outpouring of Australian cinematic talent of the past few years. It takes as the basis of its dramatic scenario a theme that most Americans would have thought was not only thoroughly worn out but hopelessly p.c. A young girl who, having been abused or traumatised, decides to take a belated revenge on the male sex. Can you imagine the mixture of preachiness and sentimentality that such material would have elicited from Hollywood? But neither Bennett nor his heroine, Nicole (Nick) Davies (Frances O’Connor), is interested in milking her situation for pathos, and she becomes a more quirky and likeable figure than we could have expected.

The trauma of her childhood, which we witness in an attention-grabbing opening scene, was that she saw her mother burned to death by a man who threw gasoline over her and set it alight. As we watch this happening, the grown-up Nicole in voiceover is telling us of her distrust of men. Only as the film goes on do we understand, by paying pretty close attention to the unfolding of her long-delayed revenge, the circumstances that led up to this central event of Nicole’s life. So many striking characters and bizarrely criminal situations are thrown at us in the course of what looks like a picaresque, trans-Australian crime spree by Nicole and her boyfriend, Alan (Al) Fletcher (Matt Day), that we don’t realize until the end that the film, in spite of the trail of dead bodies they leave behind them, is about something else entirely — namely the spooky way in which nobody really knows anybody else.

Perhaps the film’s most brilliant scene comes as the two police detectives, who have obviously worked together for a long time and are pursuing the couple across the country, are eating breakfast one morning. One of them points out to the other that he hasn’t eaten his bacon. He doesn’t eat bacon, he says, because he’s Jewish. The other is completely incredulous. How could they have been so close for so long without his knowing that? No, the other insists, it is true. He was adopted as a child. His parents, Mossad agents on a secret mission, had been killed in a plane crash. His sister now works at the UN, his brother is a mercenary in Zaire.

All of this is news to the other cop, who grows more and more wide-eyed with astonishment. The first goes on: he is wondering whether or not to go back to the law. Back to the law? Yes he qualified as a lawyer, but he didn’t like it. So he joined the force. Now, however, he has to think of his wife and and child, he says. The partner, dumbfounded can only say, “When did you get married?”

“Oh, about ten years ago,” says the first cop airily. They have one child, a little boy with cerebral palsy.

“That’s terrible,” says the second.

“I don’t like to talk about it,” replies the first, hilariously, as he opens his mouth and eats the piece of bacon. It has all been a complete con, a joke. But it illustrates most succinctly what we are shown again and again during the course of the film, which is that not only do we really know very little of each other, but we cannot even be sure of the little we do know. How are intimate relationships possible in such circumstances? This question becomes of urgent concern when Nick takes to sleepwalking one night, fills up a bucket with gasoline and throws it all over Al. He stops her before she can torch him, but he has to tie her hands to the bed rail (with her permission) for the rest of the night.

They are apprehended by the police in the morning. Can they trust each other under police interrogation? Al will tell the cops nothing; Nicole tells them she killed everybody. “Why did you kill them, sweeetheart?” the cops ask.

“Because they’re men; I kill men,” she says.

But both we and the cops begin to sense that the story doesn’t add up. Once again, we know far less than we think we do — about Nicole, about Al, about the cops and about everybody they meet along the way. This state of affairs becomes for us a given of the human condition. Yet the final scenes suggest that love is, nevertheless, possible. Or so we think.

This film meets what is to me the true test of cinematic greatness, which is that, however outlandish or exotic the events and characters it portrays, it is at some level about the life that we all lead, and the traumas and heartaches we have all experienced. Don’t miss it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.