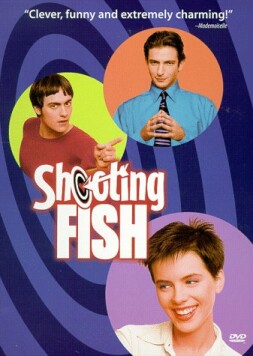

Shooting Fish

Shooting Fish by Stefan Schwartz stars Dan Futterman and Stuart

Townsend as Dylan and Jez (short for Jeremiah), an American and an Englishman

who team up to run various scams in the interests, they say, of some orphans,

namely themselves. If this strikes you as a jolly jape, you may be as much stuck

in the 1960s as Mr Schwartz and you are certainly the kind of person for whom

this film was made. The 60s motif is prominent throughout, from the the lovable

rogues to their androgynous accomplice, Georgie (Kate Beckinsale), to the Burt

Bachrach tunes that dominate the musical score. “We are good guys,” says Dylan

to Georgie when she begins to question their illegal acts. “You just have to

trust me, OK?” And the same goes for us.

Only in the movies! The madcap British comedy of the 60s introduced us to

these types, whose studied unconventionality (Jez and Dylan live in a water

tower where they stash the money Dylan, the fast-talking con-man, cheats people

out of and where Jez, a mechanical genius, invents things) is meant to bespeak a

free spirit. The

“irreverent”

and

“absurdist”

touch comes as the Queen decides she doesn’t like her picture on the

£50 notes and recalls them all while

our boys are in a state of temporary incarceration. As it happens, their stash

of £2 million just happens to be in

£50 notes, and the old

£50 notes cease to be legal tender on

the day before they are to be released from prison. They must call on the

services of Georgie to spend their money, but first they have to get her the

keys. The funniest part of the film comes as she tries to spring them from

prison for a day for a fake funeral — but she has her own ideas about how

the money should be spent.

The characters and the situation are a kind of mass-market knock-off of Joe

Orton’s wickedly subversive dramas of

the 60s and, like them, are set against a background where authority is

ridiculous, if not much more ridiculous than everything else. There is just a

hint or two of the political here. Why don’t the boys put their money in the

bank? asks Georgie. “And help the rich get richer?” Jez replies. Likewise,

Georgie’s rich fiancé (Dominic

Mafan) is obviously a jerk who has to go. But the mildly political is cancelled

out by a broad sentimental streak. The point of all their hustles is to raise

enough money so that they can buy a stately home for themselves: two lads who

grew up in orphanages — Dylan in New York, Jez in London — who have

arrived home at last.

The touch of fondness for the memories of old-fashioned British aristocracy,

particularly for its other-worldliness (a quality that Jez shares) is also

redolent of the 60s, as is the happy ending involving both love and a

heartwarming story about victims of Downs Syndrome rescued by the Robin Hoods in

spite of themselves from being put on onto the street. Or something. All this

60s stuff also helps to establish the context for the marriage-like compact

between Dylan and Jez, which is glanced at more than once. The final resolution

restores heterosexual regularity to the relationship by means more or less

frankly miraculous.

Shakespeare lovers will recall that the Bard did something similar in 12th

Night, where the sexual ambiguity of two budding homosexual relationships is

suddenly resolved to the world’s

satisfaction as the guy turns out to be a girl and the girl turns out to be a

guy. There the subversive suggestion is that love is more likely to end in

tragedy than the sort of ending that is what we will. Shooting Fish has

no such purpose, but only offers a campy send up of traditional stage lovers. I

am not prepared to say that such a movie, with such a view of the world, can

never be much good, but it wasn’t much

good in the 60s and it isn’t much good

now.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.