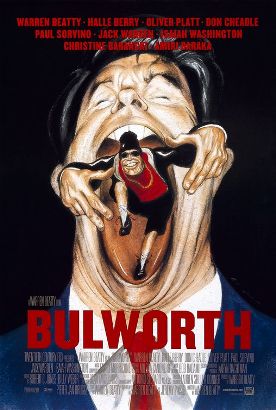

Bulworth

Bulworth is Hollywood political fantasy from one of Hollywood’s inveterate political fantasists, Warren Beatty, who is both director and star. Like The American President, which starred Beatty’s wife, Annette Bening, this movie proposes that the ticket to electoral success in America is a frank and robust avowal of socialist principles by hitherto cowardly and mealy-mouthed politicians. Is it possible that Warren Beatty really believes this to be the case? Does he genuinely suppose that a politician who starts dressing up like a black rapper and spouting obscenities on TV in pursuit of a left-wing agenda would be a hot electoral property? It seems improbable, but the idiocy of his policy prescriptions (most prominently for socialized medicine) is such that his political judgment may be equally poor.

As in The Rainmaker and other products of the casually liberal Hollywood culture, the insurance companies are convenient bad guys. Here they are represented by Paul Sorvino doing his classic Godfather impersonation on behalf of those rapacious insurers who have the nerve to object to government plans forcing them to give money away to the poor. In what is depicted as a corrupt bargain, Senator J. Billington Bulworth (Mr Beatty) agrees to bottle up in committee the bill requiring them to do so in return for ten million dollars in life insurance on himself, his daughter to be beneficiary. When the wicked insurance man agrees to the deal, not knowing that Bulworth has just lost everything he had in pork-belly futures, the Senator proceeds to plot insurance fraud by employing a hit man to kill him before word of his ruin comes out and causes him to be defeated in an impending Democratic primary.

Relieved of the need to play the game and rendered lightheaded by days without food or sleep, Bulworth starts letting the politician’s mask slip and speaking frankly for a change. This strikes some of the black constituents in South Central to whom he is speaking at the time to think that he’s a funky sort of politician, and they take him around to a black club where he is bitten by the rap bug. His learning to use obscene slang becomes the outward and visible sign of his new inward authenticity. He is also attracted to the sexy Nina (Halle Berry), who turns out to be mixed up in what some might call stereotypical ghetto crime. Not for the first time in the movies, most recently in A Friend of the Deceased, a man who has marked himself for death suddenly discovers (too late?) that he wants to live on—in this case and in spite of his fat cat lobbyist friends and his cokehead chief of staff (Oliver Platt) to impose his ruinous political program on his fellow countrymen.

And why not when it is all so easy? The insurance companies may be beyond redemption, but the drug dealer (Don Cheadle) who employs black children in what he calls “entry-level positions” is inspired by Bulworth’s example into more socially responsible drug dealing. A little obscene rap on national television and the country is clamoring for socialized medicine. When Beatty talks with nostalgic regret for the loss of “black leaders” like the thug and murderer, “Huey” Newton, Nina reveals that her mother used to be a Black Panther and proceeds to develop a nonsensical theory about the decline of black leadership and the erosion of the manufacturing base in the inner city which Bulworth later appropriates as his own, to similar applause.

To catalogue the political idiocies of this film were as tedious as pointless, but its real purpose is less to sell particular policies than it is to make a further contribution to the Warren Beatty mystique through the recurring persona of the eternally young, devastatingly attractive (the luscious Miss Berry proves the latest of his conquests by saying coquettishly, “C’mon, Bulworth, you know you’re my niggah”) charismatic idealist cut down like a Kennedy in his manly prime. Beatty is clearly in love with this image of himself, but it is hard to believe that anyone else can be.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.