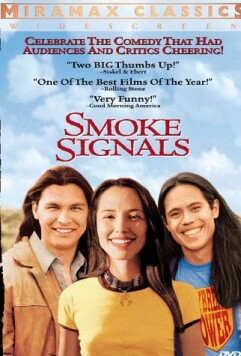

Smoke Signals

People who are obsessed, as so many people are these days, with racial,

ethnic, or sexual identity must lead very dull lives, for it is ridiculously

easy to entertain them. In Whatever, for instance, I heard be-sandaled

feminists burst into hoots of laughter when one woman told another that she

wishes her scruffy-looking daughter would take more trouble over her appearance.

Similarly, in Smoke Signals, directed by Chris Eyre from a script by the

hot young American Indian writer, Sherman Alexie, the audience in whose company

I saw it seemed to find it amusing when one Indian on the Coeur d’Alene Indian

reservation in Idaho asked another for something in return for a lift — in a

car she drives only in reverse — by saying: “We’re Indians, remember? We

barter.” It was also taken as funny when the second Indian repaid her with a

story (not a very interesting or plausible story, it has to be said) and she

said: “A fine example of the oral tradition.”

Do Indians really talk like this to each other? Not having spent a lot of

time with Indians, I cannot say, but it seems improbable on the face of it.

Would a disk jockey at a ramshackle reservation radio station, KREZ, greet

listeners by crowing: “It’s a good day for being indigenous”? And would his

fellow indigenes think it particularly witty of him if he did so? Maybe I am

just suspicious by nature, but this kind of thing sounds to me the teensiest bit

inauthentic. These are jokes intended for the white man, I think. The racially

self-conscious white man. Who else would find it funny when two Indians start up

a chant about John Wayne’s teeth, or one Indian undertakes to instruct another

in how to be an Indian by saying: “Indians ain’t supposed to smile like that;

get stoic.”

The best joke in the movie, judging by the audience reaction, came as a young

woman thanked two young Indians for helping her by saying that they were “like

the Lone Ranger and Tonto.”

“No,” says one of the lads. “It’s more like we’re Tonto and Tonto.” This

produced gales of hilarity, but I couldn’t quite see it myself. One wishes, of

course to be polite toward our indigenous brethren, and to encourage their

charming artistry, whether in beads, rugs or movies, but patrons should be

warned that this is the artistic apogee to which the film ascends, and the rest

of it is a pretty grim slog.

True, it does have a serious purpose. Victor Joseph (Adam Beach) and his

buddy Thomas Builds-the-Fire (Evan Adams) undertake a trip from Idaho to Phoenix

to fetch home the ashes of Victor’s father, Arnold (Gary Farmer), who walked out

on his family ten years before. Both young men owe something to the old man,

since Thomas, an orphan living with his grandmother, was saved by Arnold from

burning in the conflagration that took the rest of his family on bicentennial

day, July 4, 1976. When Granny tells him that he “did a good thing,” Arnold

Joseph starts to cry. “I didn’t mean to,” he whimpers.

This would have been a better line had we not found out later on that he also

started the fire and may have gone away partly because he was so guilt-stricken

about it. But the whole thing is designed to lead up to the concluding poem by

Mr Alexie, read in voiceover on the soundtrack, called “Forgiving our Fathers.”

Forgiving them for what? For, as the poem makes clear, just about anything and

everything including (I guess) being Indians and not being Indians. There is a

certain poignancy to the Indian’s half-way status, to be sure, but I wonder if

the Indians themselves feel it quite as much as the white liberals for whom this

film is intended?

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.