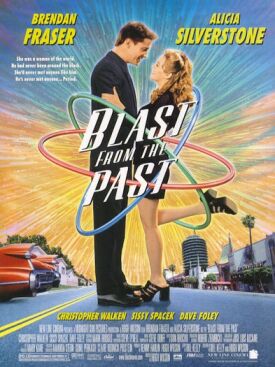

Blast from the Past

Blast from the Past, directed by Hugh Wilson, is a charming, funny, well-crafted and even touching comedy that deserves the large audience I expect it will attract. This is the more remarkable as it is the fourth time (at least) that Brendan Fraser has made this same movie. First he was Encino Man, a prehistoric hominid unfrozen into contemporary Southern California. Then he was the obscure baseball superstar plucked by Albert Brooks from mysterious obscurity in The Scout. Then he became George of the Jungle, the man-ape of the comic Tarzan knock-off. But all of these were essentially the same character: the innocent, raised in isolation from the world as we know it and brought into the w.a.w.k.i. in order to help us see it, as Candide or Gulliver do, with fresh eyes unspoiled by familiarity with its characteristic corruptions and hypocrisies. All of the earlier roles of this sort were primarily excuses for Hollywood’s brand of juvenile humor and made little or nothing of the potential for seriousness in the concept.

Well, fourth time lucky. Mr Fraser’s newest Candide is called Adam, a child born in a fallout shelter, whither his parents, Calvin and Helen (Christopher Walken and Sissy Spacek), retreated in 1962 in the mistaken belief that World War III had started during the Cuban Missile Crisis. True, the idea that they managed to stay down there for 35 years is a bit feeble, but it is well worth giving the film its improbable donné. Mr Fraser’s sudden emergence into the late 1990s with all the attitudes and values of the late 1950s intact, as imparted to him by loving parents, produces a lot of trivial, Encino Man-type humor but also a very serious look at what the intervening four decades of progress have cost us.

Calvin is supposed to have made money as an inventor on leaving Cal Tech, but to be a bit of a nut in his politics ( “Don’t mention the Communists,” whispers one guest to another at the party which begins the film). As he is a brilliant and rich scientist, both the fallout shelter itself and the education he gives little Adam are accounted for, and as he is a little paranoid about the commies it accounts for his staying down there for so long. Adam is a fluent reader at age three, when his proud papa says: “I’d like to see the public school system match that, I don’t care how great it is.” Later he learns French, German and Latin, history, geography and science. He learns boxing from his father and dancing from his mother—dancing as she had done it in her youth in the 1940s. He learns perfect manners.

Calvin looks forward to coming out of the shelter eventually, into the supposed aftermath of nuclear Armageddon, to “rebuild America the way it used to be.” Meanwhile, above his head, where builders unaware that it is there have built a malt shop over the entrance to his bunker, a moral devastation almost thermonuclear in its completeness is taking place. Listening to the building from deep inside the earth, Calvin says, “Something is moving around up there.” Then the film cuts to a flash-past montage of the decade of rock’n’roll and sex and drugs and social upheaval. Mom’s Malt Shop becomes an ever more seedy bar, its clientele a compendium of social ills. Beneath their feet, in the time-capsule, Calvin and Helen are turning into an old middle class couple of the 1950s, Calvin becoming even more of a stick in the mud than before, Helen bored and drinking too much.

Of course, Adam emerges and finds his Eve (Alicia Silverstone), who is predictably spooked and repelled by a man who treats her with respect. What’s his game? And yet she is drawn to him too, and agrees to help him find a wife—if possible, one from Pasadena, which his mother tells him is where nice girls come from. But no mutants. Dad agreed to his finding a girl, but “not one that glows in the dark, I hope.” And he has to find her in two weeks. “I could probably get you laid in two weeks,” muses Eve, “but to find a non-mutant wife in Pasadena might take some time.” It’s a good joke, but overall this is the weakest part of the picture when it ought to be the strongest. Miss Silverstone, who is running to chubbiness, overdoes the hardbitten bit and doesn’t allow us to like her enough. And the ingenue’s by-now almost obligatory gay sidekick, Troy (Dave Foley), doesn’t add anything we haven’t seen too often before.

Still, these seem like minor quibbles in light of the film’s many excellent moments, one of the best of which comes as Adam, having been taken by Eve and Troy to a club in search of a wife, shows what he can do on the dance floor. It is by chance that he arrives just as “swing” is making a comeback, but that it has done so not only makes Eve realize she is falling in love with him but raises hopes both in her and in us that some of his other skills may make a comeback too. Afterwards, Eve and Troy discuss Adam’s unfamiliar deportment. “Good manners are a way of showing people you have respect for them,” Troy explains to her, never having thought of the subject in this light before himself. “I thought it was a way of acting superior.” They look at each other with what the poet Keats would have called a wild surmise, as if their unexpected glimpse of what it might be once again to be ladies and gentlemen were, like stout Cortez’s discovery of the Pacific, both frightening and awesome. And it is, too.

Don’t write to me about Balboa, by the way. It’s Keats’s mistake.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.