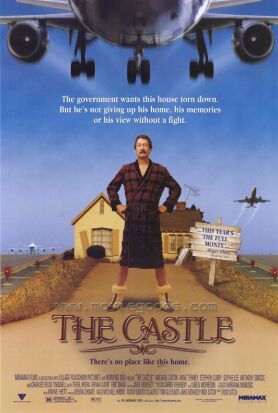

Castle, The

Readers will divide in their reactions to the very funny Australian film, The Castle, directed by Rob Sitch, according as they are disposed to see its presentation of the Australian equivalent of trailer-trash as patronizing or not. As I have rather a high tolerance for ridicule—of others if not of myself—I am inclined to find it inoffensive. What makes all the difference, in my view, is the fact that Sitch and his co-writers clearly like the tow-truck driver, Darryl (‘Daz’) Kerrigan (Michael Caton) and his family whose story they tell. The very names of Daz and his wife Sal (Anne Tenney), his daughter Tracey (Sophie Lee) and sons Steve (Anthony Simcoe), Dale (Stephen Curry) and Wayne (Wayne Hope) are in their native Australia enough to brand them as belonging to the lower social strata, as are the facts that they raise and race greyhounds and have an ever-varying collection of second-hand junk in their yard and dozens of kitschy figurines and other trophies of the sort produced by the Franklin Mint in their house.

But their hearts are in the right place, and when Home Sweet Home is slapped with a compulsory purchase order so that Melbourne airport, just over the garden fence, can build a new cargo center, they decide to fight it with the help of their hilariously incompetent family solicitor, Dennis DeNuto (Tiriel Mora). Cast in the role of the little guy who fights city hall, Daz is a natural hero, and we love him not only for his stubbornness but also for his guileless sweetness of nature which goes way beyond mere naïveté and approaches the sublime obliviousness of the Holy Fool. Nor is such innocence unconnected with his role as champion of hearth and home against an uncaring state. Sitch shows us so much of the Kerrigans’ home life not only because it is funny but also in order to make the point that it takes both love and a certain amount of judiciously deployed stupidity to sustain a family.

In Daz’s eyes, for instance, neither Sal nor the kids can do any real wrong. His son, Wayne, is in prison for larceny, but Daz never reproaches him, visits and supports him in prison, regards his incarceration as if it were just a misfortune, like injury or illness, and never appears to doubt that Wayne will go straight when he gets out. More importantly, neither does Wayne. Tracey is a marvel of artistry as a beautician, and when Sal serves chicken or meatloaf, Daz acts as if it were some fantastically tasty exotic delicacy. When she protests that it is only meatloaf or chicken, he says “Yeah, but what did you do to it?” He also insists on admiring her “creativity” as a potter and often says to her, “You should open a shop” to sell the hideous and useless pots she keeps making.

Naturally, the wife and kids respond in kind. Dale (pronounced “Dell” ) does a running voiceover narration in which he admiringly repeats Dad’s little sayings and nuggets of wisdom. He introduces us to the family’s favorite vacation spot, an ugly lake in an unprepossessing landscape called “Bonnie Doon,” by telling us that Dad appreciates the “serenity” of the place. And, he adds, “if there’s one thing dad loved more than serenity, it was an outboard motor on full throttle.” Somehow the sting is taken out of such irony when it comes in the context of familial love and support. So when it looks as if Dad has lost his case and is dejected at having “let down” the family, young Steve speaks up to say: “Dad, you haven’t let anyone down. I don’t know what the opposite of letting someone down is, but you done the opposite.”

In short, as Daz says, “I think we’re the luckiest family in the world.” The absurdity of his refusing to move out of his ramshackle house filled with junk and subject to airport noise at all hours of the day and night begins to take on a larger, symbolic significance. “I don’t want to be compensated,” he says. “You can’t buy what I’ve got.” This is not just sentimentality. Or stupidity, for that matter. For Daz is something of an expert on the subject of what money can buy. He and Steve, whom he calls “an ideas man,” seem to spend most of their spare time buying and selling things advertised in the classified ads of the local shopper. Every time Steve suggests getting in touch with a seller of some article of merchandise, Daz asks its price and, when told, replies as regularly as clockwork, “Tell him he’s dreaming.”

Daz at least, in spite of appearances, is not dreaming. He represents in all kinds of ways the vulgarity and tastelessness of the consumer culture which in the latter part of our century has conferred its dubious benefits even on those as humble as he is. Yet somehow, through it all, he has retained a true sense of the value of things. In fact, somewhere not far beneath the surface of this film, and perhaps of Australian culture too, there lurks the suspicion that it is precisely his cluelessness when it comes to matters of taste and aesthetics which guarantees a corresponding moral shrewdness about “common sense”—he’s not sure where that clause in the constitution is, but he’s sure it’s in there somewhere—and common values. The film attempts to evade the sentimentality of such a conclusion by means of its unrelenting ridicule at poor Daz’s expense, but most of us will not be fooled. Whatever the reason he is as he is, he is a hero for our time.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.