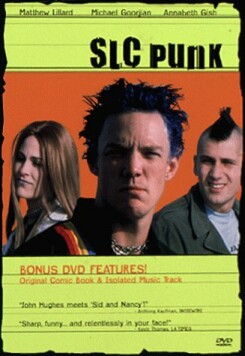

SLC Punk

SLC Punk is another teen movie, but one with a serious purpose that is

not lost sight of in the first five minutes. Obviously based on the personal

experience of the writer-director James Merendino, it presents us with the

inherently comic picture of a post-high school punk rocker, called Stevo

(Matthew Lillard), and the not very extensive punk scene in Salt Lake City in

the mid-80s. Unfortunately, the inherent comedy of the situation is not enough

by itself to make the picture worth watching, and Merendino does little to add

to the comic energy by presenting, for instance, some dramatic confrontation

between Stevo and his friends and representatives of what they merely complain

about as “a religiously oppressive city, which half its population isn’t even

that religion.”

In fact, apart from a couple of fights with punk enemies such as rednecks,

mods and mock-punk “posers,” the very existence of either “oppression” or

“rebellion” is left to be inferred — in the film as, one suspects, in real

life — from the punk adoption of the rhetoric and symbols of the latter. “We

were going to waste our lives,” says one of them; “it was the only way we had to

rebel.” That is presented as a witty paradox, rather like Marcuse’s idea of

“repressive tolerance” — and there is one rather amusing scene in which

Stevo tries with indifferent results to defy his ridiculously over-tolerant

liberal parents. But when you think about it for more than a couple of seconds

the idea is both absurd and pathetic, a kind of moral suicide resulting from

sheer boredom.

The picture’s great virtue is that, in the end, Stevo is made to see this, or

something like it. “If the guy I was then met the guy I am now,” he says in

voiceover after his translation from Salt Lake City to Harvard Law School, “he’d

have beaten the s*** out of him.” Briefly he pretends to have entered the

training ground of the haut Establishment only the better to thwart it,

since he “could sure do a lot more damage inside the system than outside it.”

But the concluding note is of self-enlightenment: “I was a goddamn poser,” he

says. Well, yes. But he, like Merendino, remains sentimentally attached to the

pose, which is why they have attempted to engage our sympathies over the

preceding 96 minutes for what amounts to nothing more than immaturity and

self-delusion. Like the punk revolution, it is a hopeless cause.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.