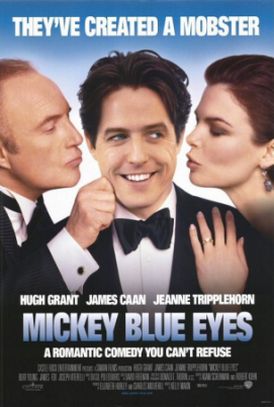

Mickey Blue Eyes

First westerns, then horror films, now gangster flicks: all the great Hollywood genres have been appropriated by the spoofters and turned from serious melodrama— in living memory, the movies have become the one place in the aesthetic world where the expression is not an oxymoron— into comedy and parody. Hard on the heels of this spring’s Analyze This comes Mickey Blue Eyes, directed by Kelly Makin, in which once again the familiar trappings of the mafia family—including even the actor Joseph Viterelli whose bulk and massive, cauliflower nose and cratered face make him the perfect embodiment of the movies’ idea of mafia muscle—are brought forth onto the screen just for laughs.

Let me say at the outset that the movie is very funny. At least bits of it are. I liked Hugh Grant’s very English talent for self-deprecation in the role of Michael, an auctioneer for a very proper, Sotheby’s-like establishment, who falls in love with and wants to marry an inner-city schoolteacher, Gina (Jeanne Tripplehorn), who turns out to be the daughter of mafia chieftain Frank Vitale (James Caan). Miss Tripplehorn does an adequate job as the girl, but the excellent Mr. Caan is wasted, I think, in a role which is just badly conceived and incoherent. Likewise, Burt Young as the head of the mafia family, Uncle Vito, and James Fox as Michael’s boss, the buffoonish Philip Cromwell, are given too little to do and are not quite believable characters.

The film’s worst fault is that it is too knowing, in a movieish sort of way, about its subject. At no point do we have the feeling that these are real mafiosi. They are movie mafiosi, and this movie is not only unashamed of the fact, it positively relies on it. At least in Analyze This, Robert De Niro’s character pretended not to know that he was only a movie mafioso. Even the perpetual smirk of Billy Crystal was held in check just enough for the movie’s central illusion—that the mafia guy was being treated for anxiety attacks by a nerdy but terrified psychiatrist—to be precariously sustained. But Mickey Blue Eyes never even pretends to be about real mafiosi. The guns, the tough-guy talk (whence Michael receives the soubriquet of the title), the dark hints about “whacking” people are just the trappings of the genre whose incongruity in the high-toned world that Michael inhabits generates much of the comedy, like Michael’s comically halting attempts to say “Fugheddaboudit” or “Getoutaheah” in a New York accent and with a New York attitude.

But the result is that a lot of other possibilities for humor are sacrificed. Why, for instance, does Frank suddenly take such a liking to his prospective son-in-law? It can’t be, as he says, just because Michael is in love with Gina and is “some one who knows how she deserves to be treated”—which is “like a f****** princess.” In the dénouement, Frank is willing to sell out honor and family not just for Gina but for Michael too, since he could have saved the former by sacrificing the latter. Even Sicilian omerta is no match for his sudden infatuation with this diffident if charming Englishman.

Yet the film refuses to recognize that there is anything extraordinary about this relationship and not only misses out on much of its comic potential but leaves poor James Caan, as the smitten one, wondering what on earth he is doing here. Likewise, the idea of a young mafia hothead (not unlike the character played by Mr Caan in the original Godfather) who takes up painting and begins to fancy himself an artist—though his paintings are graphically violent and tasteless and have titles like “Die, Piggy Piggy, Die, Die”—would seem to have some considerable comic potential. But once the device is used to get Michael and the auction house drawn into the mob’s criminal activities, and then to bring about the revenge plot that produces the finale, it is simply dropped.

What remains, besides some good one liners (Michael announces that he’s not going to be put off marrying Gina, “not by Vito the Butcher or Vinnie the Baker or anyone involved in any kind of food preparation”) are a few comic sketches which exploit the kind of embarrassment humor that has become Hugh Grant’s stock-in-trade. In one, for instance, he tries to insert his proposal to Gina in her fortune cookie in a Chinese restaurant, but it all goes wrong. In another, Uncle Vito, on meeting Michael for the first time, asks for a foreign perspective on “all these killings” in New York. Taking a deep breath, Michael replies: “Well, to be honest, I can’t say I really approve, but if it’s all part of your business. . .”

Frank has to explain: “He meant the shootings at Gina’s school.”

Such moments make this movie worth the price of admission and confirm Mr Grant’s status as a comic leading man in the tradition of his namesake and fellow Englishman, Cary Grant, but it is hard not to feel that the movie has missed its chance to be really good.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.