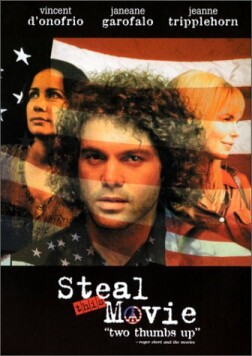

Steal This Movie

It’s almost unbelievable that at this distance of time someone could make a

movie about Abbie Hoffman which is utterly without any sense of irony about or

detachment from the eccentric views of the late Yippie leader. They used to say

about the Bourbons that they had learned nothing and forgotten nothing, but

Louis XVIII was nothing like so tenaciously obtuse as the by-now aged hippie

aristocracy, or at least that portion of it which dominates our world- beating entertainment

industry. Steal This Movie, written by Bruce Graham and directed by

Robert Greenwald blithely gives Hoffman (Vincent D’Onofrio) credit not only for

stopping the war in Vietnam but for the successes of the civil rights,

environmental and women’s movements as well. He’s the the Walter Mitty or, to

bring the comparison up-to-date, the Al Gore of the old New Left — or he

would be if he hadn’t killed himself in 1989, on the eve of the triumph of the

one political development for which he really does deserve some credit — if

that’s the right word.

For the film’s attempted transformation of a pathetic prankster and

intellectual lightweight into one of the seminal figures of the age only

reinforces our sense of the essential nullity he stood for. Not only the

“anti-war movement” (which really ought to have been called the “don’t-draft-me

movement”) of the 1960s but most of the new political causes that were

contemporary with it and subsumed under the umbrella of “the movement” tout

court were not, or were only minimally, matters of politics as traditionally

understood. They were, rather, political theatre. Politics has always been part

theatre, but always before the theatrics had serious real-world causes and

consequences. Abbie and his Yippies invented the idea of political theatre for

its own sake. That was the point of Revolution for the Hell of It, which

gloried in its detachment from anything like real political issues.

Thus was born the politics of moral posturing which has had such a belated

success in the post-Cold War mainstream with the election of that well-known

feeler of other people’s pain and hippie manqué, Bill Clinton. Yet only

by reading between the lines of Mr. Graham’s clunky screenplay can you begin to

see the connection between the two. Instead he tries to impart some wholly

factitious and unhistorical drama to a story which had nothing but drama in real

life, by using the by-now hackneyed framing-device of an investigative

journalist, David Glenn (Alan Van Sprang), who tells the story as a by-product

of his quest. This is to find evidence that will expose the allegedly “secret”

counterintelligence agency, COINTELPRO, and its persecution of Mr Hoffman. When

the fictional Glenn gets a peek into Abbie’s FBI file he announces that “the

son-of-a-bitch was right!”

In reality, COINTELPRO was discovered and dismantled in the course of the

Watergate investigations, and any legal problems which troubled Abbie Hoffman

after that — including his arrest for drug-dealing, after which he skipped

bail and “went underground” — were more than likely to have been of his own

making. And even if they were not, there is nothing staler than stale paranoia.

Abbie’s belief in a government conspiracy against him, in his persecution and

pursuit by the duly constituted authorities of the American Republic for no

other reason than the heterodoxy of his political views, however justified it

may have been at the time, now seems merely quaint. The idea can only create a

sense of wonder (or, in some of us, regret) at a time when the government saw

hippies as subversives instead of being run by them.

Of course, the political theatre is the heart of the Abbie Hoffman story, and

the film gets as much of this right as is consistent with presenting Hoffman as

a hero. His consort, Anita (Janeane Garofalo), and Johanna (Jeanne Trippelhorn),

the mistress he takes while on the lam, do what they can to make him seem a

serious person. “That is, like, the sexiest guy I’ve ever seen in my life,” says

Anita on first meeting him. Abbie, for his part, says “If I had been born a

woman, I’d have been Anita.” True love! But the nearest we ever get to political

thought is when Abbie announces that “The problem with liberals is that they see

every side of an argument; and what happens then? Paralysis!” To him and his

allies, Socialism means “everybody gets some” and this seems quite enough of a

reason to “dive into the fray of life and help start a revolution.”

“We’re there, dude!” echo the Seattle and convention protestors across the

abyss of time, though few of them are likely even to know who Abby Hoffman is.

The best joke occasioned by this movie — which at one point shows its

subject causing a disruption at the New York Stock Exchange by throwing money

onto the trading floor and announcing that “We proclaim the death of money and

the birth of a new society” — comes in Mr Greenwald’s comment to an

interviewer from the New York Times about how he got his movie financed.

“We got very lucky,” he said. “There was something called a hedge fund. I’ll

never understand what it is, but they had the money and wanted to invest it.”

Somehow, I think Abbie would have approved.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.