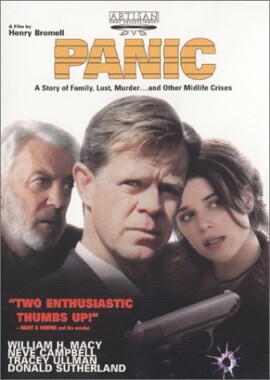

Panic

Panic, written and directed by Henry Bromell, does a fine job of

setting up the classic therapeutic paradigm so beloved of the theorists of what

they call

“patriarchy.”

This it does, I take it, for political reasons, since the very existence of

“patriarchy”

depends on an explicitly political assumption, namely that there is some

realizable alternative to the sexual status quo which is ipso facto not

only better but compelling in its demands to be realized by political action.

Yet the political dimension of this movie is almost entirely implicit, and it

can be enjoyed by those who do not share its left-wing assumptions. In other

words, this is a movie that the film schools and other academics will love and

yet, remarkably, it is not half

bad—given, that is, that you can

suspend your disbelief long enough to watch it.

The story concerns a very special kind of patrilinear succession: a family

business, passed from father to son, in contract killing. The set-up, that is,

already establishes the film’s

fundamental identification of masculinity with violence and slaughter, but these

things are meant to be seen as domesticated. A certain amount of black humor is

generated by clichés like “your

father built this business up from nothing by

himself” in the context of murder. In

this it is like Analyze This only with a much more serious subtext, like

The Sopranos only politicized. Like both, too, it makes use of the

central device of a killer, bound by masculine ideas of honor, who visits a

therapist because he is haunted by the human implications of what he does as a

matter of duty and obligation or, as the

film’s patriarch, Michael (Donald

Sutherland) puts it,

“destiny.”

The cheerful assurance of Dr. Parks (John Ritter) that

“therapy is as common as gasoline;

it’s what keeps us going” is

charmingly glib, especially when we see immediately afterwards the smile die on

his lips as his patient, Michael’s son

Alex (William H. Macy), tells him that he kills people for a living. Clearly,

therapy is not what has kept him going. Moreover, it quickly becomes

clear that what he wants therapy for is not to go but to stop. Of course he is

confused, and when the therapist asks him why he has sought counseling he

answers: “I don’t know…I’ve never

been to a shrink before. I don’t believe in shrinks. I mean we are what we are,

right?” Here he is echoing his father,

whom we see in flashback teaching the boy Alex how to shoot a squirrel and

explaining the meaning of destiny: “It’s

who you really are. It’s who you’re really meant to

be.”

But Alex is going through what is fashionably known as a

“mid-life

crisis”—another way of saying that he

has come to doubt his destiny. The one thing he can explain about his feelings

is that he feels dead. His relationship with his wife, Martha (Tracey Ullman),

has been strained to the breaking point by his inability to talk to her about

what he does for a living, and he is clearly dominated by his father, who is now

settling into a genial old age as grandpa to

Alex’s adorable young son, Sammy (Liam

Aiken). Equally clearly, Alex’s own

relationship with Sammy is based on sharing and lots of quality time at home. We

can tell that he is a father determined not to be like his own father.

Alex finds a hope of escape in his attraction to a hairdresser and fellow

patient at the therapist’s office,

Sarah Cassidy (Neve Campbell). Here, too, there is a political subtext, since

Sarah is bisexual. “I like pussy, all

right?” she says to the therapist at a

point where she is unconscious of her fellow patient and his attraction to her.

“Why are you looking at me as if I

kill people for a living?” Sarah the

lesbian (we see her a-bed with a fellow hairdresser) thus becomes a vision of

escape into a feminized world that remains just out of reach for Alex. It is a

world promising freedom from the exacting demands of masculine honor and

reticence which have made a monster of his mother, Deirdre (Barbara

Bain)—a woman co-opted by the masculine enterprise and by his

father’s need of a confidante who has

now become daddy’s enforcer.

“Your father worked hard all his

life to make this business…and now you want to break his

heart,” she says to him when he talks

vaguely of quitting. “Are you getting

enough from Martha lately?” mom goes

on to inquire. “Men don’t get their

sex and they get wacky, and you are talking

wacky.” Note the pun on wacky and

whack, the slang term for contract killing. It is because he wants to get

un-whacky that Alex wants to quit, but of course his father

won’t let him. It is only when the

patriarch undertakes to introduce Sammy to his

“destiny”

as a man and a murderer that Alex is galvanized into bringing his long-buried

“issues”

with dad to a crisis.

Panic is a remarkably well-made film. It will give you an excellent

idea of what the other side is up to without being manipulative or making you

gag at its obvious tendentiousness. Now if only someone would make a film about

a masculine

“destiny,”

especially one involving violence (where is Rocky when we need him?)

where the patriarch was not the inevitable villain.

But is that even possible anymore?

“Business is business, Alex; a job is

a job,” says veteran actor Donald

Sutherland with something like real conviction but in a savagely ironic context.

In one hilarious flashback, daddy takes the young Alex on his first hit.

“You did it

kiddo,” he exclaims.

“I’m so goddamn proud of

you!” Could such lines appear in a

movie today where they were not ironic? I doubt it.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.