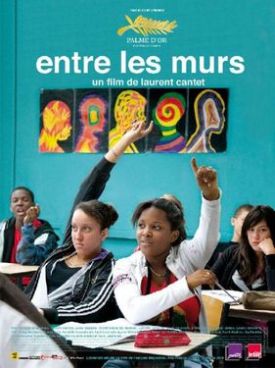

Class, The (Entre les murs)

Recently, our new Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, warned that we had been “lying to ourselves” about education in America — and lying to children and their parents as well — “because states have dumbed down their standards.” If he really believes this, it will be interesting to see if he hangs on to this belief instead of being captured by the educational culture which, under Democrat and Republican administrations alike for the past 40 years, has insisted on keeping the charade going. The liberal and multicultural assumptions, under which whatever education remains must now take place, show no signs of loosening their hold on the educational establishment, but it is at least a hopeful sign that some of those within that establishment are occasionally willing to drop the façade and tell the truth. “Sometimes, you have to call the baby ugly,” says Mr Duncan.

I thought of those words as I watched Laurent Cantet’s wonderful film, The Class, based on François Bégaudeau’s book, Entre les Murs — which title, I take it, implies some such English equivalent as “Walled In” or even “Inside,” as prisoners say. The claustrophobic sense of being locked in to a confined space with a mostly hostile gang of teenagers is the first of many challenges to our complacency about what actually goes on in many urban schools, in America as well as France. M. Bégaudeau himself co-wrote the screenplay and stars as François Marin, a French teacher in a Parisian school of the 20th arrondissement, most of whose pupils — played here (marvelously) by real French schoolchildren rather than professional actors — come from other countries in Africa, Asia and the Caribbean.

They retain strong cultural ties to their countries of origin, as we would expect under the régime of multiculturalism, which is even more influential there than it is here, and as a result the youngsters, who seem to range in age from 13 to 15, have few ties to France or each other — let alone their teachers — except for sporting (soccer) or pop cultural ones. Moreover, most come from traditional honor cultures and so have little idea about rationalist and legalistic ways of looking at the world, as poor M. Marin finds out when he tries to explain that his punishment of one of them doesn’t arise out of personal animus or revenge but only a disinterested wish for their betterment. Under the circumstances, his teaching of the French language and literature is bound to be seen by them as at least as much as a provocative act as a usefully educative one — an attempt to socialize them into a society and a history that they only know how to despise.

Of course, the multiculturalists, with their dread of anything that smacks of “cultural imperialism” are singularly ill-equipped to teach them otherwise. François is liberal-minded and well-intentioned, but he lacks the confidence in himself and his subject matter that would be necessary for success as a teacher. At one point he freely confesses to his pupils that only a snob would ever use the subjunctive mood — and then he has to explain to them what a snob is! That, however, is probably just one more in a series of what the British call “wind-ups” or attempts to get the teacher’s goat by pretended ignorance or offense. The kids are savvy enough to know how to do this by embarrassing the teacher’s liberal and multicultural sensibilities, as when M. Marin uses the name “Bill” in a grammatical example, and the kids take turns complaining that he always uses “white” names — various racial epithets and derogatory equivalents of “white” then follow — instead of names like theirs.

They all know what schoolchildren the world over know but that teachers are now officially encouraged to forget, namely that they are engaged in a power struggle with M. Marin. And, as in any contest where one of the contestants doesn’t know he is in a contest, the result is predictable. The children naturally delight in taking advantage of what he doesn’t know — or, rather, of what neither the law nor the educational bureaucracy nor his own liberal principles will allow him to admit. We, however, can see it very clearly in his first encounter with the class. When he asks the kids to write their names on a piece of paper, the one who is instantly identifiable as the chief trouble-maker, a girl named Esméralda, refuses to do so until he does the same. It is the kind of challenge to authority on the grounds of a specious egalitarianism whose outcome will determine everything that follows, and naturally he fails to meet or even recognize it, agreeing with Esméralda that he should write his name as well.

Thus does he invite the contempt for his own authority that is henceforth to be his lot among these youths. Thereafter, calculated affronts and acts of disrespect to the teacher continue until he is goaded into an outburst of some kind or, even worse, he leads the offender down to the principal’s office and leaves him there — only for the principal to give the offender even more of a feckless talking to than he himself would have done. Marin’s stake in believing that it is possible to teach these kids while treating with them on terms of equality and sweet reason is obviously very high, since he clings to it in spite of one blow after another to the assumptions on which it is based. But he is actually somewhat more clear-sighted than most of his fellow teachers and the vast educational bureaucracy they are all a part of. All are as much the prisoners (entre les murs again) of these assumptions as he is, but their failure to realize it produces one painfully comic moment after another.

One of my favorites takes place during a teachers’ meeting during which someone moots a proposal for a points system, like in driving. Each kid would start with six points and then have points taken away for bad behavior. When they get to zero points, they must go before a disciplinary committee. When someone complains that this would simply give the little devils a free pass on bad behavior until they had used up all their points, the principal reasonably proposes that they could arrange a system in which they would forfeit all the points at once — whereupon the most sensible member of staff says, “Then what is the point of having the points in the first place?” Nothing is resolved and they move on to a discussion of the coffee machine in the staff room which, they are told, “must be economically viable.”

On this showing, the everyday life of the school revolves around the question of what to do about the disciplinary hard cases because there is nothing to be done about them except, in the extreme case, to expel them and so — for such is the law — send them on to another school. From the next school they will naturally most likely be expelled as well, but by then they’re somebody else’s problem. It’s the educational charade as musical chairs. At some level, he himself sees the absurdity of his own position and the false assumptions on which it is based, but he appears powerless to do anything about them. One of the most telling moments in the film comes when a history colleague approaches M. Marin with the idea to coordinate his own teaching about the ancien régime with his colleague’s French texts. How about Voltaire? he suggests. “The enlightenment will be tough for them,” says Marin, ruefully. It’s tough for everybody nowadays!

The pathos that lies in this dawning recognition of the principal character of his own self-contradiction, together with that of his helplessness to do anything about it, constitutes the great virtue of the movie. There is an almost tragic sense of pity and terror in seeing him reduced to such helplessness. He is a sort of King Lear of the classroom, mocked and disrespected by those whom he and they both know he should command but can no longer. The loss of his dignity, like that of Lear’s, is comic and pathetic at the same time, but he hasn’t even got Lear’s prospect of death to render it tragic. Rather, the tragedy seems to be that of the one boy, Souleymane, who is expelled — because of an accidental moment of “violence” — and, as a result, is likely to be sent back to a miserable life in Mali by his strict father.

There would have been no need for this expulsion if Marin could have been allowed to exercise just a modicum of discipline over his charges. But that is not permitted, either by the authorities or by his own over-sensitive liberal conscience. At one point, even the dinner lady in an empty cafeteria exercises an authority superior to his own by telling him to put out his cigarette. “I thought, since no one else is here. . .,” he stumbles pathetically. But, deep down, he must know as well as we do that he is no longer a moral agent in his own right but only the helpless spokesmen for the liberal order on the one hand and the helpless victim of the class’s contempt and disrespect on the other. Who, you might think, would ever be a liberal? And yet the world seems to be full of them.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.