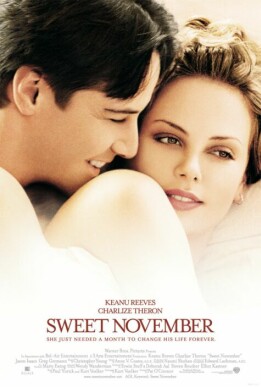

Sweet November

I should say that I have not seen the original film of 1968 which inspired

the remake of Sweet November, written by Kurt Voelker and directed by Pat

O’Connor. But I have seen so many

films so much like it — admittedly not

many of them recently — that the remake

looks very familiar indeed. Though set in the present day, it has about it the

authentic musty smell of the 1960s, a decade in which it was possible to enjoy a

certain amount of theatrical success merely by having your hero tell off his

boss, or not wear a suit to work one day. The national obsession with

“conformity,”

dating back to the 1950s and the myth of the

“organization

man,” ultimately produced a succession

of cinematic free spirits in movies from Breakfast at

Tiffany’s to Easy

Rider, from A Hard

Day’s Night to A

Thousand Clowns, who were the harbingers of that herd of non-conformists

gathering, by the end of the decade, at Woodstock. Or the Pentagon.

The Holly Golightly type who educates the up-tight, sober, workaholic hero

with the help of an eccentric

gentleman — or

lady — who lives

upstairs — or downstairs — was a

remarkably adaptable figure. Even Jane Fonda got to play her, to Robert

Redford’s up-tight lawyer, in Neil

Simon’s Barefoot in the Park.

Simon, however, as entertainer-in-chief to the bourgeoisie, made them a chastely

married odd-couple. Usually the woman with the free spirit was also free with

her sexual favors, and the title of Sweet November referred to its

heroine’s endearing habit of taking a

new lover every month. The original featured Sandy Dennis in the role, that of

the “partly woman but mostly

child” Sara Deever, and Anthony Newley

as her devoted November.

Miss Dennis (she died in 1992) was an actress whose entire career, which

pretty much petered out after 1970, depended on her playing similar roles. She

had that fragile, waif-like appearance that seemed sexy for a brief period in

the 1960s (think of Twiggy). The remake gives us the strapping South African

lass, Charlize Theron, as this lovable gamine while the wooden Keanu Reeves

plays Mr Uptight, the man who comes to joyous, uninhibited life under her

guidance. And that is to say nothing of super-butch Jason Isaacs, the

unforgettable British bad-guy in Mel

Gibson’s The Patriot, who has

been pressed into service as the eccentric gentleman and life-adviser who lives

downstairs. Naturally, as this is San Francisco, this person is a drag

queen.

If these casting decisions sound like good ideas to you then by all means go

see this movie. And stop reading this review. Not only will I have nothing more

to say to you, but I mean to reveal the ending, since it provides the only

insight into what the film’s creators

might have thought they were doing by such eccentric casting. For there has been

a subtle change in the 60s message. Then it was: be free, do what you want, live

selfishly, since nobody can tell you what to do without your permission.

Nowadays this insane but once-persuasive counsel would presumably go down less

well, so it has become something more like an innocuous exhortation to make more

time in your busy schedule for loved ones and to be nicer to people at work. And

animals. And drag queens.

Well, who can argue with that? The fact is that contemporary audiences

don’t want to be told to change their

lives in any really radical way. That fancy-dressed, quit-your-job 1960s-vintage

Bohemianism won’t play so well today,

though American Beauty had a rather successful go at reviving it in

another form. It’s OK for Sara for the

same reason it was for the hero of American Beauty — because (as we

find out near the end) she is about to die. She is therefore not just a free

spirit, taking up a new

“case”

as her lover every month, but someone who is herself trying to get the most out

of life before snuffing it from cancer. And her final gift to poor

Keanu — with whom, of course, she has

fallen in love as he has with her — is

to send him back to his world of advertising and lattes and workouts with

nothing but a memory. “If you leave

now,” she bravely tells him, meaning

before she is helpless and bed-ridden,

“everything will be perfect

forever.”

“Life isn’t

perfect,” says Keanu, reasonably

enough.

“All we have is how you remember

me: you’re my

immortality,” she persists, clinching

her case by saying: “I need this. .

.just like I need to know that you’ll go on and have a beautiful

life.” And so, amazingly, Keanu turns

his back on her to return to his

“beautiful

life” of advertising and lattes and

workouts, which is presumably even more beautiful now that, thanks to her, he is

not such an a******e. It is, in other words, a movie whose paean to the virtue

of selfishness — a selfishness, of

course, only of the

“nicest”

sort — is further exalted by another to the virtue of cowardice. For those

who like this kind of thing, this is the kind of thing they will like.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.