Mob Hit

The return of The Sopranos to HBO last month for its third season reminds us once again of what a great work of American art this collaborative venture, headed by David Chase, still is. Although it suffers from the twin disadvantages, either of which might seem certain on its own to be artistically lethal, of being both a TV soap opera and a work of post-modern whimsy, it somehow manages to combine them so as to become the greatest of television soap operas, a work of post-modern whimsy which is also a work of art. Who’d have thought it possible? The series transcends the limitations of its medium and style and becomes not so much a kind of modern Homeric epic as what modern Americans would have if they had a Homeric epic.

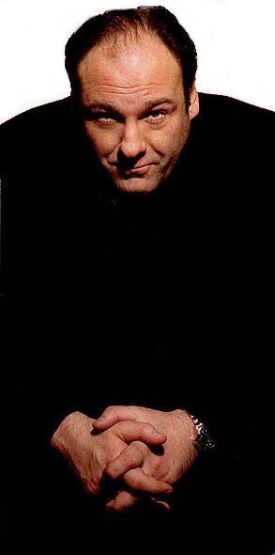

Perhaps it was a somewhat similar point that Caryn James intended to make when she wrote in The New York Times that the reason for the series’s “wide appeal” was its fusion of the inevitable mundanity of television with playful references, intended for the cognoscenti, to high culture, as when a taste of prosciutto becomes for Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) what the madeleine was for Marcel Proust. The show, she wrote,

lives at the juncture where pop culture and high art meet. Functioning on the levels of capicola and Proust, of movie lovers and film scholars, “The Sopranos” speaks to middle-class people like Tony as well as those above and below him on the real-life social scale. Remarkably, it does not talk down to a mass audience or assume an elitist tone.

Well, you can see how the masses would flock to it! It must be very gratifying to them to know that they aren’t being talked down to while at the same time their betters are “getting” the highbrow allusions to Proust! Indeed, Proust’s experience with the madeleine is laboriously recounted by Dr Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) to Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) just so the dummies in the audience can be kept on board.

This is actually the least successful moment of the new series, it seems to me, a straining after significance of which the two earlier series were hardly ever guilty. But Ms James’s is far from being an idiosyncratic opinion. Indeed, to read much of what has been written on the series is to be persuaded that a great deal of the critical praise which has been heaped on it is owing to the fact that the critics were flattered by getting the jokes. Here, for instance, is what David Lavery, a professor of “English” (i.e. “popular culture, film studies and science fiction”) at Middle Tennessee State University, wrote at www.poppolitics.com:

“Any text that has slept with another text … has necessarily slept with all the texts the other text has slept with,” notes Robert Stam, author of Film Theory: An Introduction (Blackwell, 2000), extending a central premise of STD prevention into the study of literature and film. Our times, by this logic, are clearly promiscuous. It is quite apparent that many of television’s most ingenious series — rife as they are with intertextual references, often humorous, to movies, to culture in general, to literature, to (self-referentially) themselves — come heavy [with allusion] as well [as “The Sopranos”]. The predominance of the “already said,” as Umberto Eco once observed, is, after all, one of postmodernism’s signatures. Often, the intertextuality of such shows contributes mightily to keeping a certain segment of the audience — flattered by “inclusion-by-allusion,” able to feel pride in the ability to get the references — still hooked, still watching.

It’s an Internet kind of point to make isn’t it? Here is the critic as search-engine, sniffing out intertextuality wherever he finds it and spitting out a report on the number of hits. That, at any rate, seems to be how Lavery understands the critic’s role. Quite what it has to do with criticism as it has traditionally been understood, I don’t know, but it does have the advantage of making a lot of work to keep the professoriate happy. My own search engines each offered me over100,000 hits when I typed in “The Sopranos,” and this number can only increase, to the advantage of PhD programs in “communications” everywhere.

Lavery, perhaps from necessity, confines his intertextual scavenger-hunt to pop-cultural allusions, but Caryn James is clearly carried away with the Proustian theme:

And while the series’s reference to Proust is funny [she goes on], it is not frivolous. As no single film or ordinary television series could, “The Sopranos” has taken on the texture of epic fiction, a contemporary equivalent of a 19th-century sequence of novels. Like Zola’s Rougon-Macquart series or Balzac’s “Comédie Humaine,” “The Sopranos” defines a particular culture (suburban New Jersey at the turn of the century) by using complex individuals. So what if Tony is not a prostitute out of Balzac but a mobster out of David Chase’s imagination? His outlaw status offers a way of assessing mainstream society in all its savagery and hypocrisy, even while the series creates a unique family history.

I may be wrong, of course, but I think this is nonsense. “Mainstream society” might be savage and hypocritical, but if so we see very little of that in “The Sopranos,” where almost all the savagery and hypocrisy belong (as we might almost have expected) to the gangsters. That, indeed, is the point of their being gangsters. For the show is not social criticism like Balzac or Zola, but something like its opposite. Instead of using the “outlaw” or outsider to point up the evils and injustices of “society,” Chase and his colleagues are assuming the bland and comfortable decency of the most prosperous and egalitarian society the world has ever known and using it simultaneously to criticize and to express a sneaking admiration for those who persist in living their lives under assumptions and according to rules that ceased to make very much sense to most people in the dominant culture approximately half a century ago.

Tony Soprano, that is, is a reactionary and not a progressive hero, a sort of Don Quixote. Like the Don he is a deluded anachronism whom we nevertheless love for his devoted attachment to the old ways, the ways of honor and chivalry and patriarchal family arrangements — a devotion that would be pathetic if it were not, intermittently, so dangerous (to say nothing of illegal). In this sense the professors are right. Like all mock heroic, the series depends on our knowledge of the heroic tradition it is sending up — in this case that of the gangster movie. So an understanding of the references and allusions to that tradition are important in the way that some knowledge of Ariosto or Tasso was important to the first readers of Don Quixote.

It is also possible to imagine that “The Sopranos” will do for the gangster film what Cervantes did for Ariosto and Tasso, that is make it almost impossible for us to appreciate them except through the eyes of their parodist. As in Cervantes’s time, reality has undergone one of its periodic shifts in the direction of the familiar, the mundane, the domestic and the unheroic. But if Chase and company share even so much nostalgia for the putative golden age of honor as Cervantes (or, a fortiori, Balzac), they keep it pretty well-hidden. And rightly so. We wouldn’t buy Tony Soprano as the parfit gentil knight he occasionally sees himself as being. But neither would we find him sympathetic in the least if it weren’t for a tiny but ineradicable residuum of respect of our own for the idea of a life lived, however imperfectly and, indeed, brutally, according to honor.

Or, to put it another way, what makes the series compelling is not its criticisms of “society” vis B vis the mafia, though there are some of these. Instead, we are drawn in by the assumption that even the scary and solidly established world of organized crime — mysterious and romantic and solemnly real as the movies have made it to us throughout their history — cannot stand up against the overwhelming banality of the consumer culture in turn-of-the century suburban New Jersey with which it is juxtaposed in a mock-heroic way. As in Don Quixote, the absurdity of the hero’s chivalric delusion cuts us off from supposing that it is meant to represent to us any kind of genuine alternative to the “society” we have actually got. In any case, we like that society and its benefits too much. Its permanence and inevitability are everywhere assumed. That, indeed, is the secret of Tony’s attractiveness.

For we know that ultimately, he and his way of life don’t stand a chance against the onward march of progress and therapy and niceness. If he weren’t, like Don Quixote, doomed by the delusion that he is living in a different time and according to different rules than he actually is, we would not find nearly so much comedy and pathos in his attempts to cling to an anachronistic Mediterranean honor culture at odds with everything around it, or in his own intermittent yielding to the same forces of progress and therapy and niceness — as when in season one he is proud of having refrained from “whacking” his daughter’s high school soccer coach who had molested one of the girls on the team. “Carmela, I didn’t hurt nobody,” he cries triumphantly while pumped full of booze and Prozac, perversely (for a gangster) proud of a tender-heartedness like that of his wife and the would-be genteel suburban culture he envies in spite of himself.

Again and again similar points are made in the new series. In the opening episode of the season, for example, FBI agents obtain a “sneak and peek” order from a judge to plant listening devices in the upscale suburban villa which Tony Soprano shares with his wife Carmela (Edie Falco) and two children, Anthony Jr. (Robert Iler) and Meadow (Jamie-Lynn Sigler). When they do so, however, they find not criminal activity (though Tony’s phones have been bugged for four years, “the guy says less than Harpo Marx” an FBI agent complains) but one thing after another that proclaims their common commitment to consumerism. One notices that Tony has the same Black and Decker power tools he has. Another at first envies his large capacity, 140 gallon water heater — until he notices the corrosion that suggests “that baby’s going to blow.”

“Too bad we can’t warn him,” says one of the agents sardonically, but the joke is on them when the water heater does “blow,” thus causing them to have to abort their first attempt to plant their bug. Then, after they have planted it, the first thing they hear is Tony talking apparently about a mob hit: “It might get a little messy,” he says, and there is a reference to “wet work.” Naturally, the ears of the listening FBI agents perk up until they realize that he is talking to his maid’s husband, Stachow, an engineer from Lodz who is trying to become a citizen, about fixing the blown water heater. As always, the potentially heroic is constantly dissolving into the boringly domestic. Thus, too, the lament of Uncle Junior (Dominic Chianese) at the funeral of Tony’s mother (Nancy Marchand) that “they’re dropping like f***ing flies,” elicits from Tony the reply: “It’s all that charbroiled meat you guys ate.”

“Nobody told us until the ‘80s!” moans Uncle Junior

“I’m kidding!” says Tony. But the authors are not. Mortality among gangsters, as among the rest of us, is more likely to be a matter of excess cholesterol than of what used to be thought of as the gangster “lifestyle.” Thus the most likely reaction of the listening authorities to what they hear in Tony’s basement is neighborly concern rather than anything else their snooping could elicit. Fifteen-year-old Anthony Jr is observed smoking outside a convenience store and plotting some mischief with a friend. The Polish maid is overheard telling her husband that she is stealing champagne glasses — and maybe other things. Most shockingly, two agents disguised as power company linemen observe one of Tony’s disgruntled “soldiers,” suspecting (rightly) that Tony ordered the murder of his twin brother, training his pistol on him through the kitchen window. What should they do?

Fortunately, they are spared the necessity of deciding when the man lowers his gun. Not to spoil the general deflationary tendency vis B vis the familiar heroics of gang warfare, the show has him turn instead and urinate in Tony’s swimming pool. It is a curious sort of revenge — like that of the waiter who spits in the soup. And like the waiter it reminds us of the only slightly-hidden class dimension to the story. For in the consumer paradise what arouses our passions is not so much revenge anymore as envy. You can detect the distinct note of it as the FBI agents covet Tony’s oversized water-heater. “They have so much,” says the champagne-glass-swiping maid to her husband. In the first series there were suggestions that the upscale neighbors didn’t like Tony not so much because he killed people as because he was just so nouveau.

This is to some extent an attitude shared by David Chase and the series’ creators — and, of course, the pointy-headed professors wielding their “intertextuality” engines. The charm of tough guy Tony for them is pretty obviously that he allows them to feel superior because they recognize the allusions he was created, in part at least, to miss. Thus is Don Quixote transformed into M. Jourdain, MoliPre’s Bourgeois Gentilhomme, to those who, perhaps, scrambled out of the gutter one generation ahead of him. In one of the new episodes, for example, Carmela’s tennis instructor (an article which is itself an accoutrement of the arriviste) announces that he is moving to California where his wife has a job with a dot-com company selling antiques over the Internet. He suggests that he can get her some bargains in exchange for some recommendations to show his new, Californian clients, but Carmela replies: “I don’t have antiques; my house is traditional.”

As we are with Tony’s many malapropisms and other signs of ignorance (Dr. Melfi even has to explain who Proust is for gawdsake!), we are being invited to laugh at the social pretensions of these uncouth barbarians fresh from the streets, for whom “traditional” means the week before last, but our egalitarian principles give us no twinge because the barbarians are also criminals and do horrible things to people. We tell ourselves that it’s OK to despise their vulgarity because they’re also evil. But it is a tribute to the genius of Chase and Co. that the process also works in reverse, as it were, since their ignorance about the word “traditional” is made up for by their deep knowledge of a traditional reality that is much older than any antique.

Therefore, at the same time the object of the series’s satire is also the pseudo-culture of therapy and feelings and sensitivity that has taken the place of the old honor culture represented by Tony and the boys. This is true, obviously, in the person of Dr. Melfi, but also in the mindless liberalism of the Soprano children or the New Agey claptrap spouted by Tony’s ne’er-do-well sister, Janice (Aida Turturro), who announces at her mother’s wake: “Most of you will probably remember that I have an extraordinary visual sense.” Tony himself fitfully aspires to join the aristocracy of feeling, as in the moment when he congratulates himself for not killing a child-molester — though most of all, of course, in his continuing to see Dr. Melfi and to listen, however reluctantly, to her counsel.

We both despise Tony as a failed suburbanite and admire him as an avatar of a culture that seems as remote to us as that of the ancient Greeks and that we can hardly help but see on a similarly heroic scale. Whatever else we may say about Tony, we know he is not living the life of easy comfort and self-indulgence we are, and we envy him for that even more than for his outsized water heater or his champagne glasses. At one level this means nothing more than that nobody messes around with Tony with impunity — the true mark of the aristocrat. Nemo me impune lacessit. And who would not secretly wish to make life’s little annoyances go away as Tony does? But at a deeper level we know that, unlike Don Quixote, he really is functioning as part of a world that takes honor seriously. Or at least more seriously than we do.

That’s why he’s on TV instead of being, like other recent therapy-seeking gangsters, in the movies. The movies can still take seriously the heroic pretensions and the high style associated with the world of honor and duty, loyalty and revenge; television with its anti-heroic and post-modern bias naturally undermines them. The grand themes of mob life, at least as we have learned to see it from the movies, are ambition, betrayal and revenge, but these things are rarely presented unironically in “The Sopranos.” Thus the essential ridiculousness (especially as it turns out) of one lot of suburban bourgeois breaking into the house of another lot of suburban bourgeois is hinted at on the sound track as the FBI’s cloak-and-dagger, precision operation to plant its bugs in Tony’s house is introduced with the Peter Gunn theme, which gradually gives way to and intertwines with “Every Breath You Take” by The Police.

Still, there is just enough of the traditional drama of gangsterdom to prevent Tony from becoming a figure of fun. The best thing about the series is that it is able to walk the line between the serious and the comic, the honorable and the farcical, without ever becoming wholly the one or the other. Hence the deep ambiguity of one of the most critically acclaimed moments from the new series when, after his mother’s funeral, Tony is seen watching the final scene of Public Enemy as a tear rolls down his cheek. It is a reminder of the extent to which these gangsters are self-conscious gangsters, which is to say movie-gangsters, but is Tony weeping because he falls short of the gangster ideal, or because the death of James Cagney reminds him of the gangster’s fate or because of the love shown the Cagney character by his mother as compared with his own mother’s indifference?

Most critics have assumed the last, as it best fits with the therapeutic bias of the culture, but the authors are as usual careful to preserve the uncertainty which is so much a part of Tony’s appeal. And he is also attractive to us on the level of sheer wish-fulfilment, because of the things he can get away with. As Bill Tonelli of Rolling Stone wrote in the New York Times:

The men on “The Sopranos” do what most men, in their hearts, wish they could do: spend time with one another out and about, idle and unrestrained by the civilizing presence of women in their workplace, free to drink, smoke, curse, eat thick sandwiches of meat and cheese and carry guns and fat rolls of large- denomination bills. They freely commit violence and fornicate, the very things men still do best but are most vigorously denied by contemporary codes of acceptable conduct. Superficially, the women on the show seem beleaguered, but they too yell and curse and rage and hit and smoke and eat lasagna and cannolis, even later at night than nutritionists advise.

Of course we get a vicarious thrill from him, as we do from all gangsters, for his swift way with his enemies. Everyone secretly likes the idea of commanding respect through fear, and the authors are as ruthless as Tony himself in exploiting this secret wish of our hearts, and using it to mock the liberal pieties that those who look down on Tony live by. When in Episode Four of the new season, for example, Dr. Melfi is raped by a man she later recognizes as “employee of the month” at a local fast food restaurant, it is the first thing she thinks of. She knows that she has only to mention to Tony what has happened and she can wreak the most horrible revenge on the punk who raped her.

Indeed, after this person has been let go through a police mistake resulting in a break in the “chain of custody,” she becomes almost obsessed with the idea of her own power — and with the horror she feels at the fact that she wants to exercise it. In one of the show’s best moments, she confronts her own therapist, played by Peter Bogdanovich, who has been gently chiding her for her flirtation with evil: “The justice system is screwed up Elliot. . . Meanwhile that employee of the month c********r is back on the street, and who’s going to stop, him Elliot? You?” She adds that “I’m not going to break the social compact” by referring the rapist to Tony’s tender mercies, but she cannot but mention the “satisfaction” she derives from the consciousness that, if she chose, she “could squash him like a bug.” Even the sensitive soul, Janice, cries out when she is attacked by Russian thugs seeking her late mother’s companion’s artificial leg, which she is holding hostage: “Do you know who I am? Do you know who my brother is?”

Dr Melfi, at least, is aware of a self-contradiction that is almost universal among the respectable folks who are shocked at or contemptuous of the gangsters. Most of the other characters in the series are not, and it makes special fun at the expense of Dr Melfi’s husband, Richard who is so comically obsessed with the bad name that gangsters like Tony give “Italian-Americans” like himself that his first reaction to his wife’s rape is to notice that the culprit, though Hispanic, has an Italian-sounding name. But he also says, on learning of the latter’s release back onto the streets: “I just want to find that bastard and kill him with these hands. But I can’t . . .They’d put me in jail. That’s how messed up things are.” Even he would risk conforming to the hated Italian-American stereotype if it gave him Tony’s powers of being revenged on his enemies.

Killing and disposing of the bodies of those who offend or betray one is an old forbidden thing, but the gangsters can also do the new forbidden things — things calculated to make liberal critics squirm with discomfort much more than they do when it is only a matter of murder. When Tony’s daughter Meadow comes home during her first semester at Columbia with a half-black, half-Jewish boyfriend called Noah Tannenbaum (Patrick Tully), Tony does not hesitate to warn the kid off with frank racial slurs (stunned, the boy replies after the manner of his age: “What’s your problem, man?”though the problem is clearly and very emphatically his own). Carmela warns Tony: “Keep playing the race card and you’re going to drive her right into his arms.”

“Not if I cut off those f****** arms,” says Tony.

Naturally this episode gets even more attention than the allusion to Proust. Caryn James notes that, ‘After he has warned the boy to stay away from his daughter, he tells Carmela, ‘I had a frank conversation with Buckwheat’,” but even this cannot dampen her enthusiasm for the series’s and Mr. Chase’s brilliance. It is just a sign that “far from avoiding the compromises of series television, in which flawed characters get flabby and lovable over time, ‘The Sopranos’ dares to make its hero more reprehensible.” Let’s hear it for the reprehensible hero! Tom Shales of the Washington Post takes a similar line when he notes, as it were with a sigh, that “Tony can be very hard to love, and it’s apparently going to get harder”and then he boldly ventures his only words of criticism, saying that Chase “should make much more of this incident than he does. When Meadow finds out about it, she barely registers anger much less the rage she would really feel.”

You can’t help thinking that maybe Tom Shales is missing the point a little bit here. The “rage” that he is so confident Meadow “would really feel” is what she, like her mother has been hiding from all her life. If either of them could be truly outraged at anything Tony does, there would be no family and there would be no series. Perhaps a career spent perusing the sentimental liberal pieties — particularly on the subject of race — of network TV have taken the edge off of Mr. Shales’s taste for more robust televisual realities. In somewhat the same way, Caryn James at times seems almost not to understand or even to notice the ironies she elsewhere praises:

“You know, you’re a very sensitive person for a coldblooded killer,” Julia Roberts tells Mr. Gandolfini’s character, a different kind of thug, in the new film “The Mexican” (review, Page 14). That line is so perfect for Tony Soprano that it could sweep viewers right out of “The Mexican” by reminding them of Mr. Gandolfini’s day job.

I don’t mean to suggest that she sees no contradiction between being “a very sensitive person” and “a coldblooded killer,” but at some level she must share the fundamental delusion of Dr. Melfi — and Tony himself in going to her — that the two things can be reconciled. It is to extend the highest praise to the series itself that, so far at least as we can tell from the new season, its creators do not share that delusion.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.