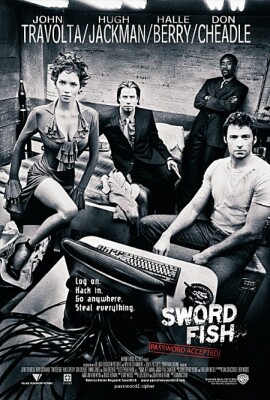

Swordfish

As an example of postmodern movie-making, the beginning of Swordfish,

written by Skip Woods and directed by Dominic Sena, takes a lot of beating. John

Travolta looking like the middle-aged dandy of which he has made rather a

speciality since Pulp Fiction, is shown in tight close-up in the role of

movie critic. “You know what the

trouble with Hollywood is?” he asks an interviewer

who is off-camera. “They make

s***.” This uncontroversial

observation he then proceeds to gloss by saying:

“I’m talking about the lack of

realism,” and he cites as his example

the ending of Dog Day Afternoon. Al

Pacino’s character, he thinks,

“didn’t push the

envelope” of what he professes to

think of as realistic movie-making.

“What if he started killing hostages

right away?” he asks.

“How many innocent victims splattered

across the windows would it take to make the city change its

policy?”

The unseen interlocutor, supposedly sticking up for movie conventions, points

out that the hostage crisis could not be seen to be resolved in this way.

“The guy can’t win. It’s a morality

tale. He’s got to go down.”

Travolta’s character then wryly

observes that “life is stranger than

fiction sometimes” before announcing

that it’s time for him to

go — whereupon the camera pulls back to

reveal that he is the chief actor in a hostage-taking that swiftly culminates in

an innocent victim’s being splattered

across the windows.

But the multiple ironies of the scene go further than perhaps the filmmakers

intended. We can pretty confidently expect that the ending of this movie

will not be “a morality

tale” — at least not the traditional

sort exemplified by Dog Day Afternoon. But the appeal to

“realism” — by

which the speaker means that outside of the movies not only do ruthless villains

neglect to build up suspense but crime actually does

pay — is wonderfully double-edged. For

by fracturing what are by now long out-dated movie conventions,

Sena’s movie produces not more but

less realism. Real hostage-takers are more like the muddled and pathetic

character portrayed by Mr Pacino than the machine-like and omnicompetent Gabriel

Shear presented to us by Mr Travolta. And they rarely if ever escape scot-free

with the girl and the money.

Nor does this film’s unrealism stop

here. One is so used to it by now, of course, that

Hollywood’s ignorance of and contempt

for politics and the real exercise of power is easily taken for granted, but

Swordfish takes it to new heights. The terrible Mr Shear, we learn, is an

anti-terrorist terrorist. The bank heist in which he kills several hostages and

police— which, by the way, makes no

dramatic sense, as the money is somewhere else and being shifted around by

computer — is to raise the funds for a

world-wide anti-terrorism campaign being secretly backed by a United States

senator (Sam Shepard) who has, apparently, unlimited use of the federal

law-enforcement apparatus to pursue his clandestine campaign. When Shear, the

senator’s

“rottweiler,”

threatens to get out of hand, he orders him killed. But the quarry turns hunter

when, after murdering a large number of federal agents in black SUVs in the

streets of Los Angeles, he shoots the senator himself in a trout-stream while

proclaiming that “patriotism does not

have a four-year shelf-life.”

These guys don’t even know that

senators serve six-year terms! But to criticize the preposterousness, not to say

the idiocy, of such a plot is, I realize, beside the point, since po-mo

movie-making positively glories in preposterousness. As it does also, obviously,

in eating its cake and having it too by making its ruthless slaughterer of

innocents a right-wing law-enforcement nut. Similarly, it loves the sentimental

cliché of having its hero, played by Hugh Jackman, motivated to help

Shear’s scheme by concern for his

beloved daughter, whom he is forbidden by law to see and whose new step-father

is a porn baron who casts his wife, the

girl’s mother, in his films. Well I

guess we know whose side to be on! But the hordes of people who have made this

the number one movie in the country presumably reason that the unbelievable plot

and the implausible characters are insignificant considerations when put next to

the exciting action photography and the snappy dialogue.

It’s not real but

it’s clever.

Well, there’s no accounting for

taste. But it is just worth pointing to one reason why such a calculation might

be mistaken. A key plot element in Swordfish has to do with illusionism.

Shear explains that he will be able to fool the feds by misdirection, a

magician’s trick perfected by Harry

Houdini. “What the eyes see and the

ears hear, the mind believes.” But

there is an essential difference between magic tricks and movies. With magic

tricks we are content not to know how the trick works. Or at least our enjoyment

of the trick doesn’t depend on our

knowing how it works. But that is because the trick takes place in the context

of reality which, we know, places limits on what is possible. But movies take

place in the context of illusion. And where all is illusion, we have to have a

sense of some underlying reality for any particular illusion to have a pleasing

effect. At the film’s climax, we seem

to see two people killed who are not killed. How did they perform this trick?

The film thinks we don’t need to know,

but I think we do. Otherwise, Hollywood is just making more s***.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.