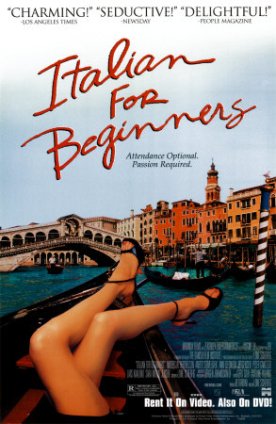

Italian for Beginners (Italiensk for Begyndere)

Italian for Beginners is a charming if slightly twee Danish film, written and directed according to the principles of the Dogme 95 group by Lone Scherfig, about love emerging from bitterness and anger and loss among people who have been damaged by these things but who have managed nevertheless not to give in to them themselves. It therefore belongs to the category of films that I have called the therapeutic romance, like The Fisher King, Return to Me or, most recently, Tom Tykwer’s The Princess and the Warrior. To my review of the last-named I refer those interested in a more general discussion of therapeutic romance. Italian for Beginners is more of a comedy than a drama-cum-fairy-tale like Princess, but its purpose is similar in seeing love more as a route to psychic wholeness than as an end in itself.

It is also slightly off-putting in its pushing of that favorite theme of Hollywood’s, the voluntary family. Miss Scherfig says in press interview that “I think with these characters a family is being formed among them. I tend to think that as we get older, we form our own families that are of our choosing. These characters are becoming adults and forming a family among friends.” Well, if you want to look at it that way. But what it boils down to is the assertion that friends can take the place of family, which is a much more dubious proposition. As in other voluntary family movies — for instance, The Object of My Affections or Flawless — the real point of crying up friends (and lovers) as “family” is to knock down real family. Accordingly, all the family relations mentioned herein are of the most unpleasant kind.

All this by way of a moral health warning to a movie that is really quite enjoyable, partly because the dialogue, though in Danish (and Italian), is clever and funny and partly because the characters are likable. And of course we are always made happy by the pairing off of likable characters that romance generally entails. The pairings-off in this case are predictable from the beginning, but that has never been of detriment to genuine romances. That there are three of them rather than just one only adds to the pleasure, as Shakespeare would have recognized.

Andreas (Anders W. Berthelsen) is the young temporary pastor at a church where the incumbent, Pastor Wredmann (Bent Mejding), has had some kind of breakdown and appears at the back of the church during Andreas’s sermons shouting: “How primitive! God exists only as a concept!” Later we learn that both Andreas and Wredmann are recent widowers, though the latter has been driven into madness, self-pity and even atheism by his wife’s death while Andreas is trying to live a normal life and only partly succeeding. He is persuaded by Jørgen Mortensen (Peter Gantzler), the clerk at the hotel where he is staying to come and join a beginners’ Italian class as a way of meeting people, since so few people come to church.

There he encounters Olympia (Anette Støvelbæk), a sweet but hopelessly clumsy assistant in a bakery. We see something of her appalling father (Jesper Christensen), with whom she lives and for whom she cares in spite of his habitual ill-temper and abuse, and we later learn that her clumsiness is the result of fetal alcohol syndrome, an even more poisoned legacy from her maternal parent. There is also a hairdresser called Karen (Ann Eleonora Jørgensen), who has an equally appalling mother (Lene Tiemroth) and who is sweet on the young man, Halvfinn (Lars Kaalund), who takes over the Italian class when the instructor dies during a lesson. Halvfinn is a restaurant manager who is fired for insulting his customers. His assistant, Giulia (Sara Indrio Jensen), is a native Italian speaker who leaves the restaurant with him, but who is fond of his best friend, Jørgen Mortensen.

Mortensen, an awkward man with no obvious talents to recommend him, confides in both Halvfinn and the pastor, telling them he is impotent. Though Giulia, who overhears, boldly tells him that all he needs is the right girl, he can scarcely imagine that someone as young and intelligent and pretty as she could be interested in him. The insecurities of all six of the prospective lovers and, in the case of Olympia and Karen, the family background that may be supposed to have caused them, are taken out and given a good airing. Can such people ever love again? But then, with a class trip to Venice, Miss Scherfig exploits the Nordic romance with the lands of the sunny Mediterranean to awaken love all round.

There is a cute scene in which Olympia asks Karen, “What do you want for Christmas?”

Karen replies: “The salon. Then I’d be my own boss. But I’d be happy with a scarf. What do you want?”

“A husband and a home and not to have to work,” says Olympia wistfully. “Or those earrings that we saw at the mall.”

This is a film about people who learn to find happiness in small things — and then get the big things as well. As Miss Scherfig put it, “I firmly believe that people can make very simple choices — just even change a habit — and they can alter the course of their life. Many of these characters are grappling with how to overcome sorrow. The simple gesture of attending Italian class is the thing that breaks a negative cycle for them and brings them humor, and passion, and love.” We should take the film in the same spirit: as a small thing that carries within it the promise and the hope of much bigger things.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.