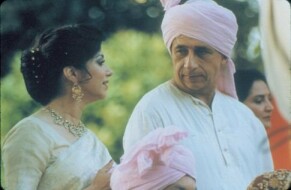

Monsoon Wedding

If I had to ask one question of a movie in order to distinguish a good one

from a bad one, or at least a less- than-good one, it would be this: Does it

start from the specific in order to get to the general, or does it start with

the general and pick up the specifics as necessary? Or, to put it another way,

do the characters make upon us an impression of being real outside the

movie’s context? Does the plot present them with adventures that appear to

have happened to them in the way that things happen to us in real life, or do

those adventures look as if they have been created only so as to elicit a

pre-ordained response? Do the authors give us the impression of having invented

both characters and plot before they knew what general principle they were to

illustrate, or is there some kind of thesis that the characters were designed

just so as to illustrate?

Although there is a lot to like about Monsoon Wedding, written by

Sabrina Dhawan and directed by Mira Nair, its answers to those questions would

be all the wrong ones. Only the patriarch of the Verma family of New Delhi,

played by Naseeruddin Shah, the arranged marriage of whose daughter, Aditi

(Vasundhara Das) to a well-to-do émigré from Houston (Parvin

Dabas) provides the “Wedding” of the title, seemed to me entirely

convincing as a real person, one who was unconscious of the job of work he had

in hand on behalf of the authors. And, good as he was, particularly in

representing the quiet desperation with which his character tries to keep the

family together and keep the money coming in to pay for its increasingly

expensive tastes, he alone was not enough to infuse the necessary dollop of real

life into a movie meant to be a sort of Indian version of an Altmanian

spectacular, self-consciously full of “life.”

The latter kind of life is of the sort to which the verbal adjective

“affirming” is often appended, and the movie is accordingly full of

comedy and tragedy, joy and heartbreak, good and bad, with an upbeat ending

designed to make us feel good — not only about the fictional characters

whom we have naturally learned to like but also about ourselves. There now,

that’s the worst thing I’m going to say about Monsoon

Wedding: that it is a feel-good picture that takes a wry and humorous look

at family and sexual relationships in the emerging middle classes of one of the

most dynamic and promising of the world’s developing countries. From any

other critic that would count as a blurb worthy of being slapped up on the

poster, but I am perverse enough to resent being told to feel good about myself.

It is of course interesting from a sociological point of view to have Ms.

Nair’s opinion that Western sexual customs are in the process of

overpowering the traditional constraints of a society like India’s, and

that with them are going such “patriarchal” family arrangements as

have hitherto managed to survive there. It is also very much to the film’s

credit, I think, that it so far refrains from taking a stridently polemical line

about those arrangements, apart from one instance which I shall mention

presently, that it can find something good to be said even about arranged

marriages. Its immense sympathy to the principal patriarch, Papa Verma, is as I

say almost enough by itself to make the movie worth seeing. But in the end one

cannot — I could not — forget the sociological point for the sake of

those who are meant to embody it.

The exception to the wry and humorous and forbearing portrait of a patriarchy

in decline comes with the introduction of the motif of child-abuse. Now I look

upon child-abuse in the movies the way I look upon the Kennedy assassination or

the Holocaust in the movies. All three bring with them their own pre-programmed

emotional responses which can only wreak havoc in the midst of the

delicately-nurtured emotions native to the particular film into which they have

been imported. Everything that the particular characters and their particular

situation can build up in the way of a particular response is tainted by this

moral enormity, which we know can only be present in order to bully us into

thinking and feeling along certain lines. It is the feminist H-bomb, and where

it is deployed nothing else can live.

The more’s the pity, as there were several promising shoots scorched to

the earth by the fireball. I particularly liked the nagging of the mother

(Sharda Desohras) of the “event planner,” who calls himself P.K.

Dubey (Vijay Raaz) and who has arranged the elaborate and traditional wedding

for the Vermas while carrying on his own flirtation with their charming

maid-of-all-work, Alice (Tilotama Shome). P.K. is a successful and enterprising sort from the lower castes who has obviously done well out of the growth

economy of new India, but his mother is unimpressed by his upward mobility. All

she cares about is that he should finally get around to arranging his own

wedding so as to present her with grandchildren. “Your father’s name will

sink without trace,” she whines to him. But of course his father’s

name has already been changed from something traditional and unpronounceable to

the Anglicized and fashionable.This kind of subtlety is too rare in the movie,

but it shows what it might have been if its makers had cared more about their

characters than about what they had to say about them.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.