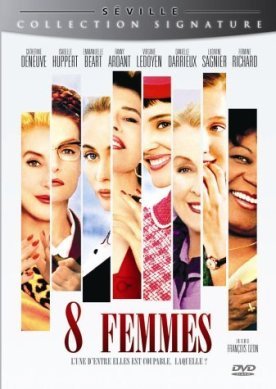

8 Femmes (8 Women)

For a movie starring so many great French actresses, 8 Femmes (8 Women) by François Ozon, is an astonishingly anti-feminist film. Set in the 1950s and taking the form of a country-house murder mystery out of the 1920s, it presents us with an all-female cast built around the body of a man with a knife in his back. We are swiftly given to understand that one of the women must have killed Marcel, and the movie appears to be going down the well-trodden path of the traditional policier. Was it his wife, Gaby (Catherine Deneuve), who was planning to leave him for his business partner but who was still the chief beneficiary in his will? Or was it his mother-in-law, Mamy (Danielle Darrieux), from whom he had sought to borrow money and who, apparently wheelchair bound, leaps up like a young doe on hearing the news of his death?

Or could it, perhaps, have been his sister, Pierrette (Fanny Ardant), a black sheep with a reputation for sexual adventurism who is trying to borrow money from him and may or may not have been heard to threaten his life. Or Madame Chanel (Firmine Richard), the cook, who is Pierrette’s secret lesbian lover? Or possibly his embittered old-maid sister-in-law, Augustine (Isabelle Huppert), whose awkward advances he seems to have spurned? Or maybe the maid Louise (Emmanuelle Béart), with whom he was having an affair? Or could it even have been one of his two daughters Suzon (Virginie Ledoyen) or Catherine (Ludivine Sagnier), of whom one is pregnant and unmarried and the other a 16 year old rebel?

We soon learn, however, that the solution to the mystery is the least of the movie’s concerns, and by the time we discover the truth it scarcely seems to matter which of the women did what to whom. All of them are charming and attractive — even poor dowdy Augustine when in medias res she undergoes a sudden transformation. All are appealing and all are appalling, and it is soon made clear that the spectacle of each of them is prepared to do — for money, love, revenge or some combination of the three — is what really kills the wretched Marcel. The female of the species, as many others before M. Ozon have had occasion to observe, is deadlier than the male.

Yet he is determined to present us with this rather vital bit of sociobiological information in the most lighthearted and jolly way possible. Therefore, as the story unfolds of a hidden history of lies, betrayals, thefts and murder which includes in one way or another all the women, each takes it in turn to burst into song on the theme of her disappointed love and yearning, her loneliness and desire, presumably as a kind of self-justification. Certainly, Ozon accepts it as such, and the good humor with which he looks at it all suggests a breathtaking sang froid. Further than this in cynicism it is hardly possible to go.

The emblematic crime is that of Mamy, who confides that she poisoned her husband, Gaby’s and Augustine’s father, even though “my needs were satisfied” and “he always treated me with respect, a true gentleman.” Despite these excellent qualities, to say nothing of the fact that he was poised to become very rich, “I couldn’t stand him.” Not-love for her is as potent a motivation as love. “Imagine,” she says, living with “a man you hated and couldn’t even find fault with.” A few nervous titters from the women in the audience when I saw the film confirmed that a nerve had been struck. Of course the man deserved to die.

Yet it seems as absurd to criticize the movie for its jaundiced view of male-female relations as to criticize an Agatha Christie for trivializing the crime of murder. Mamy offers us the culmination of the musical numbers by happily singing that “Il n’y a pas d’amour heureux” — there is no such thing as a happy love — and the grand passion of life, like the death of Marcel, is turned into a joke. What can you do but laugh? Although some of the men in the audience may feel prepared to join Marcel in drinking Mamy’s Kool-Aid, some of the ladies may quite enjoy this one.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.