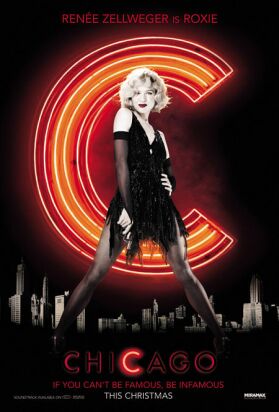

Chicago

There are many different ways for traditionalists in the arts to identify themselves, but one that occurs to me after watching Rob Marshall’s cinematic version of Chicago is to suggest that the traditionalist requires that musicals and opera include a role for innocence. There is something about the primordial impulse to sing that should be respected and that cannot quite do without it. Sometimes the role of innocence may be very small and ironic, as it is in Cabaret, for instance, where almost the only innocence belongs to those who will go on to become history’s greatest murderers. But even this is enough to put into some kind of perspective the bawdy comedy of the rest, which would otherwise grow insipid.

Needless to say, the idea of such a requirement in this case is a result of Chicago’s not meeting it — not even attempting to meet it. The movie does to us what Billy Flynn (Richard Gere) does to his clients when he assures them that they, like him, are in the know and that together they can put one over on the rubes and the suckers. Only where the rubes and suckers in Billy’s case are the members of Chicago juries in the 1920s, called upon to exonerate Roxie Hart (Renée Zellweger) and Velma Kelly (Catherine Zeta-Jones) for murdering the men who done them wrong, it is not quite clear who are the rubes and suckers to whom we are being invited to feel superior.

For nowadays we are all sophisticates, just as the school-children in Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon are all above average. Sophisticates know that the criminal justice system is, as Billy sings in one of the show’s many lively but tuneless songs, “a big circus” — just as they know that love and marriage are a sham, that men are lying, cheating scoundrels and women sly vixens with a propensity to lethal violence. At least the makers of the movie, as of the musical on which it is based, know these things, since the only person they have to show us who does not know them — besides the anonymous juries — is the pathetic Amos (John C. Reilly), cuckolded husband of Roxie, and he is merely a gull and a laughingstock.

True, he has one song, “Mr Cellophane,” whose self-pity may inspire in the audience an answering pity, but there can be no admiration or affection for someone so willing to make a victim of himself. He is living proof that innocence is a mug’s game, and when he sings — as when Roxy and Velma and Billy sing — it is more matter of self-congratulation than of self-expression or genuine feeling. At least with Roxy and Velma, the self-congratulation is for their cleverness and sexiness, about which there can be no two opinions.

On Broadway, the invitation to feel superior works better, since part of the Broadway experience is the sense of belonging to an élite. Of course you’re a sophisticate; that’s why you’re watching a Broadway play. The rubes and the suckers are everybody who doesn’t watch Broadway plays. But that sociological raison d’etre doesn’t translate along with the rest of the material to the movies. The movies are watched by everybody. They’re too democratic to invite their audience to feel superior to others.

A clue that the filmmakers understand this difficulty comes during the credits, when we are solemnly notified as follows:

“Richard Gere’s singing and dancing performed by Richard Gere.”

“Renée Zellweger’s singing and dancing performed by Renée Zellweger.”

“Catherine Zeta-Jones’s singing and dancing performed by Catherine Zeta-Jones.”

I have no reason to doubt these assurances, but they suggest a nervous awareness of the need to follow such an exercise in cynicism by assurances that, although everything may be a fake and a sham and a con-job, here in the movie at least all is — for the only time ever, perhaps — just what it claims to be.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.