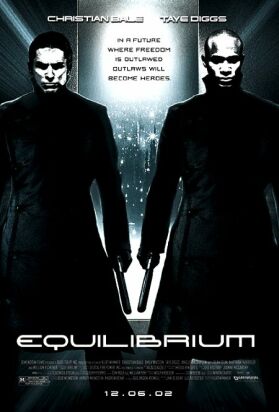

Equilibrium

Now take just a moment to think about it. In a world where television networks will spend millions in the hope of inducing a celebrity — or even a non-celebrity — to shed a tear on camera, so confident are they that we have become a nation of emotional voyeurs, is the danger that we face down the road going to come from the ruthless suppression of emotion by a right-wing government? I don’t think so. Yet that is the assumption on which Kurt Wimmer’s Equilibrium is based.

True, Equilibrium posits a nuclear war as the cause of the conversion from emotional excess to emotional austerity (to put it mildly), but the whole movie pretty much stands or falls on its characters’ assumption that wars are caused by an excess of emotion. But what if this is a mistake? If we look back to the vicious wars of the last century it is pretty hard to identify even one of them that was started by the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings of “anger” or “hate” or “rage.”

And even if we grant for the moment this dubious psycho-social theory of how wars happen, how to explain Wimmer’s dystopian élite’s failure to make elementary discriminations between kinds of feeling. Where is the logic in saying that pity and tenderness must be suppressed so that people may not feel anger? Who says that emotion is an all-or-nothing proposition? Where did that idea come from? And would you rather that your fate, or the world’s fate, lay in the hands of someone who could feel or someone who couldn’t feel?

The ruthlessness of the authorities in liquidating any people who refuse to take their “prozium” to eliminate feeling, or who cultivate a taste for art or music or poetry, is a standing rebuke to the assumption on which their rule is based. All the violence committed by unfeeling authority — and what a lot of it there is! — in order to force an unwilling population to stupefy itself with drugs can hardly be considered as a means to the suppression of organized violence, even by people as stupid as the authorities here are represented as being.

Christian Bale plays John Preston, a monk-like “cleric” who is charged with sniffing out the evidences of feelings and of artistic connoiseurship in “the nethers,” the relatively lawless and undisciplined urban hinterlands surrounding an Orwellian core where the police and the government, headed by “Father,” who never appears in public, reign supreme. When he catches his partner and fellow cleric (Sean Bean) reading Yeats on the sly, Preston shoots him dead. But then one day he forgets his own “interval” of prozium and finds himself beginning to feel. He remembers how his late wife was executed for “sense crime” and forms an attachment with another young woman, (Emily Watson), who is headed for the same fate.

The moment of his full realization that he has become a member of the Resistance rather than one of its persecutors comes when he is overseeing the execution of some captured Resistance leaders’ pet dogs. Making its escape from the canine holocaust, an adorable little puppy comes straight up to him and licks his face. The audience of hardened critics laughed out loud at this bit when I saw it, but I wonder whether a larger audience will be any more indulgent?

Even more ridiculous are the Matrix-like gun-battles in which Mr Bale is apparently able to slaughter dozens of armed assailants by leaping about acrobatically and dodging their bullets while he himself, untouched, shoots with both hands and unerring accuracy. This highly valuable skill brings him into the very presence of the Father whereupon — but I’ll not give away the exciting ending even though you are not the readers I take you for if you can’t guess it for yourself.

Also like The Matrix, however, this movie will probably be watched by youngsters whose only knowledge of the world comes from movies and who therefore will not be so forcibly struck as one could wish by the ridiculous implausibility of it all. Yet there will be plenty for them to like, such as the scene — the first in which Mr Bale does his leaping around and bullet dodging — shot entirely in the dark and lit only by the muzzle flashes of frequently discharged weapons. Well, why not make it in the dark, since he dodges the bullets by intuition anyway? Like him, the visuals are very cool.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.