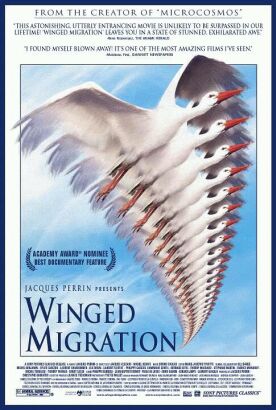

Winged Migration

Winged Migration, produced, written, directed and narrated by Jacques Perrin was one of the nominees that lost to Michael Moore’s bumptious Bowling for Columbine in the Best Documentary category at the Oscars, so allowing Mr Moore to do what he does best and make an ass of himself. According to the account I read, M. Perrin, though French and therefore a representative of the “Old Europe,” was not happy about the presumption with which Moore pretended to speak for him and the other nominees. But, speaking as an American, I should like to have seen him as the winner anyway, if only to demonstrate that even in Hollywood there is an alternative to American narcissism.

Alas, there’s probably not, or Winged Migration could hardly have failed to win any award for which it was nominated, let alone a mere Oscar. It is a visual experience that, once seen, will never be forgotten. Using ultralight aircraft, balloons, gliders and parachutes, Perrin and a number of different cameramen managed to catch birds in flight in virtual close-up, certainly as they have never been seen before, and the result is not only breathtaking in its beauty but unexpectedly moving. There are many moments here when it is hard to watch without blinking back the tears.

This is not because of any striving after effect, though there is a bit of that too, but because the mystery and beauty of the workings of nature have rarely if ever been better captured. In addition to birds in flight, there are nearly as impressive pictures of birds on the ground or in the water or snow, doing remarkably intricate mating dances like the Clark’s Grebe in Oregon or puffing themselves up and booming at each other like the greater Sage Grouse in Idaho or being eaten by crabs like a poor wader with a broken wing in West Africa.

Politics is perhaps just hinted at in shots — which turn out to have been simulated — of a goose caught and mired in factory waste in Eastern Europe or in scenes of duck hunting on the Mississippi. But for the most part the human and avian are seen in a kind of benign symbiosis, and some of the most affecting shots come from migrating birds in juxtaposition with familiar human landmarks, such the Eiffel Tower or Mont St. Michel, or the cinematically resonant Monument Valley, in Utah.

All the pictures are so glorious that they should be allowed to speak for themselves, but at times Perrin permits himself a bit of a reach for the emotion. This is particularly true in his use of music. The refrain of the concluding song, for example —

Tonight I will be by your side

But tomorrow I will fly —

strikes a rather discordant and anthropomorphic note. After all, the birds are not individualists, and they all fly together — which is one of the reasons that these images of co-ordinated movement have such power. Likewise, the attempted bit of inspirational rhetoric about the migration of the bird representing a “promise of return” seems unnecessary and slightly annoying. Birds do not promise. But they do return, and that ought to be enough of a marvel all by itself.

Yet, and perhaps oddly, I would also have preferred a bit more of the mundaneness of the nature documentary that the film otherwise seems to supersede: the names of the birds more clearly given, perhaps their scientific names too, and maps to show the paths of their migrations instead of just the distances they cover and vague descriptions such as “Central Africa to Western Europe” or “the Far East to the Siberian tundra.” Precision is not at odds with poetry and need not appear obtrusively to interrupt some of the most magnificent photography that has ever been seen.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.