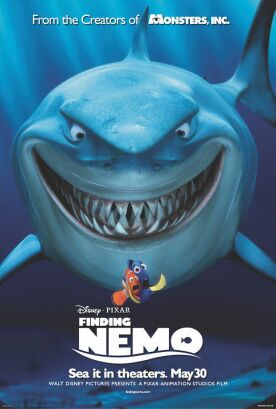

Finding Nemo

Disney’s Finding Nemo, written and directed by Andrew Stanton is the latest from the Pixar studio that gave us Toy Story, Toy Story 2, A Bug’s Life and Monsters Inc. Like those films it is almost as witty and ingenious with its computer animation as Nick Park is with his great claymation films featuring Wallace and Grommit. But in those films, and even in Chicken Run which flirts rather dangerously at times with sentimentality, Park doesn’t push his parallels too far and is content to allow the animal world to retain some of its mystery, its otherness from the human, even as he anthropomorphizes like mad. Grommit may be unlike any dog who ever panted, but he’s not really like a human being either.

That, you may not be surprised to learn, is not the Disney way. The fishiness of the fish who inhabit an Australian coral reef provides the occasional joke but is otherwise irrelevant in all but the visual sense. These are amusing human grotesques in disguise as fish, and the insouciance with which human traits are superimposed upon alien nature is finally rather irritating — and never more so than in the pretense that fish live their lives amidst nature’s profligacy with human ideas of life’s economy. What genius thought of fish, of all creatures, as parables for our one-child-per-family age? The absurdity does not work with the film’s humor but against it.

As does the typically treacly sentiment. Like Together, the film is about the bond between a father and a son, but it lets not only silliness but moralizing get in the way. After an attack by a barracuda, the clown-fish Marlin (voice of Albert Brooks) is left with no wife and but one offspring from the 400 fertilized eggs they had been expecting to hatch. This is the eponymous and terminally cute Nemo (voice of Alexander Gould), about whom dad naturally becomes over-protective until he learns how to “let go” and trust in the child’s omnicompetence, which is his birth-right as a Disney kid, however disguised.

Shamelessly, they even give Nemo a gimpy fin and allow him to be netted by a Sydney dentist (Bill Hunter) who intends him as a present for his horrid god-daughter Darla, a known fish-killer. Marlin strikes up an acquaintance with another colorful tropical fish called Dory (voice of Ellen DeGeneres), whose comic schtick is that she has no short-term memory — perhaps she has suffered a blow to her fishy head? — and together they go on a quest to find little Nemo. Their adventures are intercut with Nemo’s career in the dentist’s fish tank, where he wins the loyalty and assistance of the rest of the marine life, some of it almost as cute as himself, as well as a passing pelican called Nigel (voice of Geoffrey Rush) in making an escape attempt. There are no prizes for guessing the ending.

But neither is there any doubt that kids will love this movie. My guess is that they will love the things that adults will love too, such as the three sharks in a 12-step program (“Fish are friends, not food”), one of whom, Bruce (voice of Barry Humphries), suffers a grievous relapse at the scent of blood in the water, requiring the other two to stage an intervention. “Here’s Brucie!” says the toothy psychopath as he corners poor Marlin and Dory in a cranny of a sunken submarine.

The allusion to Jack Nicholson’s performance in The Shining, like Bernard Herrman’s Psycho music accompanying the entrance of the fish-killer, Darla, will pass over the heads of only the youngest children. But one might wish that such media-savvy kids as Disney can count on to make this a hit could also be entrusted with something a little less saccharine and, well, Disneyish. Pixar’s association with the media giant is no doubt very profitable for both parties, but it cannot escape from the moral and artistic stultification that seems invariably to come with the Disney money.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.