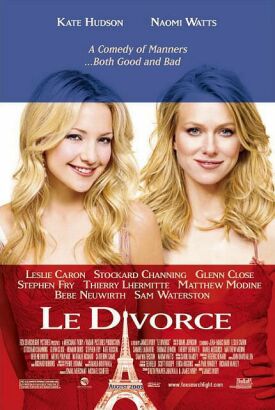

Divorce, Le

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before, but the French are a curious nation. Everything to them is a matter of taste and they consider those who, like so many Americans, make a parade of their emotions vulgar. Above all, they are hard-headed realists about sex and rarely allow mere sentiment to intrude upon their pursuit of pleasure. Oh, and they also have a flair for style, particularly in women’s clothes and accessories, and are frequently accounted masters of cuisine.

What? You knew all that already? Then there will be few surprises for you in the new Merchant-Ivory adaptation of Diane Johnson’s novel, Le Divorce. Its central conflict, between the pretty young American wife, Roxy (Naomi Watts), and the aristocratic French family of her husband, Charles-Henri (Melvil Poupaud), who abandons her for another man’s wife, is almost buried under the accumulation of banal observations about those oh-so-naughty French.

Apart from Charles-Henri, the naughtiest of all is the right-wing (and therefore presumably hypocritical) Lothario, Edgar (Thierry Lhermitte) who, with his smooth but detached Gallic charm, seduces Isabel (Kate Hudson), Roxy’s sister from California.

We learn that Edgar put exactly the same moves, with exactly the same success, on Olivia (Glenn Close), the friend and patroness of the two sisters, twenty years before — and who knows how many other women in between — all the while staying married to the same woman, who accepts his infidelities philosophically. Always his wooing begins with the gift of a fabulous, and fabulously expensive, “Kelly bag” from HermPs, and always the affair ends with the gift of a scarf. As Edgar’s older sister, Suzanne (Leslie Caron), puts it, he is “faithful only to HermPs.”

Suzanne, the family matriarch and mother of Charles-Henri, is the other prime exemplar of French sang froid when it comes to love, sex and marriage. To her, Charles-Henri’s leaving his pregnant wife is in bad taste, but it was also in bad taste for him to have married her in the first place. Being American, she is “not like us,” having no manners or self control. Americans, claims Suzanne, think manners ridiculous.

Paradoxically, however, it is Charles Henri who pleads lack of self-control: “I’m helpless. . .I know I’m in the wrong, but there is nothing I can do about it,” he tells Isabel. “Roxy should understand that” because she is a poet. Charles-Henri reminds her of her poetry’s celebration of untrammeled passion. “So all you said about the freedom to live and love was empty words?” he asks her.

“Yes,” she agrees. “When you really love, there’s no freedom at all.”

It ought to be a fascinating moment because it marks her defiance and repudiation not only of her own words but of the romanticism that the French and the Americans have in common, for all their insistence on their differences from one another. How far can her new insight be taken? To the point where she is the advocate of manners and self-control to the emotionally incontinent French?

It’s not a question that seems to interest the film-makers very much. They want to confine their wry observations of life among the French to the more trivial and obvious. When, for example, a tragedy results from the agonies of jealousy endured by the American husband (Matthew Modine) of the woman Charles-Henri has left Roxy for, we overhear a conversation between male and female French police officers, one of them assuring the other that there are no crimes passionnels in America. There all the murders are motivated by drugs or money.

Whereupon the woman officer asks for the man’s opinion of her new perfume.

It is perhaps an attempt at a French-style lightness of touch in dealing with serious matters, but the touch, if light, is not sure. It seems more like a trivialization of the serious than a quasi-philosophical attempt to put it in perspective, as in the films of François Truffaut or Eric Rohmer. Oh those Frenchmen! Ooh la-la! Well sure. But in saying so, the film forgets its own insight into all that we have in common with them.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.