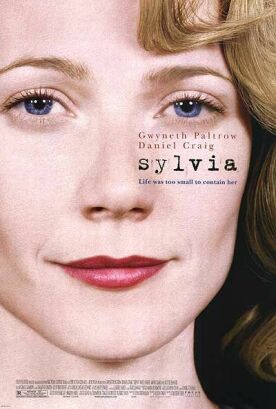

Sylvia

Sylvia by Christine Jeffs is the high-brow’s version of Kill Bill. Both movies get their kick from juxtaposing female youth and beauty with violent death and both have artistic pretensions far in advance of their actual merits. In Sylvia’s favor, at least, it must be said that Gwyneth Paltrow does a marvelous job of conveying to us the nasty and unpleasant side as well as the sweet and sexy side of Sylvia Plath.

No pale Victorian maiden she, pathetically expiring from too much reality like the Lady of Shallot. On the contrary, she is all the more hungry for what she supposes to be reality just because it is likely to kill her. Even today, her sexual aggressiveness in pursuing Ted Hughes (Daniel Craig) is slightly shocking, and no sooner does she capture his interest than she is confiding in a roommate that she has cast him in the role of her “black marauder” and insisting that “one day I’ll have my death of him.”

That kind of girlish self-dramatization is telling, but is confined in the film to her student days and unfortunately forgotten as we are encouraged to take her ever more seriously as a poet. The film begins with a passage from her poem, “Lady Lazarus”:

Dying

Is an art, like everything else.

I do it exceptionally well.

I do it so it feels like hell.

I do it so it feels real.

I guess you could say I’ve a call.

The first time I read those lines, I thought: “What a posturing ninny” — the more so as, in gassing herself in February, 1963, in order to make good on her words and show that she really was a dedicated quester after the “real,” she abandoned two small children without a second thought. I guess they weren’t real enough for her. But you’ve got to take your hat off to her prescience in gauging the rising literary market for suicide in a culture dominated, as ours was to be in the ensuing decades, by feelings.

There Miss Jeffs’ film, written by John Brownlow, rather falls down, I think. She shows Sylvia Plath as dangerous, manic, insecure, more than a little paranoid and emotionally intense, all of which qualities make for better cinema, perhaps, than poetry. But she is herself too soft, too tender-hearted not to take the poet at her own valuation, no questions asked — even to the point of having her say, without apparent irony, “I really feel like God is speaking through me.”

If it were not merely a sentimental cliché, that would be a comic blasphemy a propos of the foul stuff, including aggressive atheism, dredged up from the murky depths of the Plathian soul. And the sentiment gets in the way of Miss Paltrow’s otherwise sharply-observed Sylvia, preventing us from seeing her as not only desperately disturbed but also hugely ambitious and prepared to sell her psychological and spiritual infirmities for whatever they might fetch in the marketplace of poetic reputation.

The poetry itself — though as the Hughes estate would not give permission to quote more of it than “fair use” would allow we get very little of it — is, as A. Alvarez (Jared Harris) obligingly points out to us, striking for the coolness with which it treats horrible things and its richness of imagery. Beyond that, it would seem a form of bad taste, as well as being uncompassionate, to treat critically what it actually says. Not that criticism could affect the film’s final verdict that Sylvia has since her death become “an icon to generations of readers.”

The phrase is as revealing as it is true. An “icon” is an artefact of celebrity, an image to be worshiped for what it stands for — in Sylvia’s case, not poetry but such things as “girl power” (that’s also Tarantino’s excuse for Kill Bill) intensity and authenticity of feeling, the oppressiveness of family life and patriarchal culture, or the anger of the young against the expectations of “society.”

By contrast, a poet wants to be, as Wordsworth provocatively put it, “a man speaking to men.” Whether or not there was anything “gendered” about that idea, Miss Plath must have known that, in becoming an emotional exhibitionist, she was abandoning this real poetry for the merely pathetic poetry of the “real.”

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.