Post-Cold War Propaganda

From The American SpectatorThe history of any war is difficult to disentangle from its propaganda — and not only the official propaganda. In a way the official propaganda is the easiest to pull free of. Too easy, indeed, since we are liable to overlook those places where the official propaganda is actually true. An example was the allied propaganda mills’ publicizing of German atrocities in the early days of the First World War. These lurid stories were dismissed for over 80 years as crude, politically motivated fabrications until John Horn and Alan Kramer published German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial (Yale, 2001) a couple of years ago, demonstrating that a lot of the stories were true. But the expectation that atrocity stories would be false helped to blind people to the Holocaust in the next war.

Now we have the opposite expectation, that governments will lie and cover up — which is why there is such a fuss about those ever-loving “weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq. The propaganda of the critics of the administration about its allegedly deliberate deceptions — in effect an elaborate and not-very persuasive conspiracy theory — has become far louder in our ears than the propaganda of the administration itself. That’s one of the legacies of the Cold War, as Miracle, the Disney version of the triumph of the U.S. Olympic hockey team over the Soviets in 1980, reminds us. It’s an exciting story, excitingly told. Herb Brooks (Kurt Russell), hockey coach at the University of Minnesota, takes a bunch of college kids from all over the country and molds them into a team that takes on and defeats the mighty Russians, universally acknowledged to be the best team in the world.

I particularly liked the emphasis of the film, directed by Gavin O’Connor to a script by Eric Guggenheim, on Brooks’s own emphasis on teamwork. “I’m not looking for the best players, Craig,” he says to his assistant (Noah Emmerich); “I’m looking for the right ones.” He sees that the all-star or “dream team” approach to Olympic team sports which prevailed before and after 1980 is useless against the Russians, who have been playing together as a team for over a decade. By forcing his young protégés to come together as the same kind of team — partly by making them hate him — he gives them the wherewithal to win against the odds.

But the story cannot be told without the background of the Cold War rivalry of the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., and when it comes to filling this in, the film reveals its own propaganda purposes. For one thing, Brooks’s abrasiveness and unabashed anti-communism is toned down, almost to the vanishing point. As Russell plays him, Brooks seems weirdly unemotional until, at the point of his triumph, he creeps off into a corner and weeps. More importantly, the picture is put into the context of what Jimmy Carter was calling at the time a “crisis of confidence” in America.

Of course, there was no crisis of confidence in America; there was a crisis of confidence in Jimmy Carter. And a few months later he was booted out of the White House by Ronald Reagan on account of it. Carter had attempted to deflect attention from the Iranian hostage crisis together with high unemployment and inflation, the things that had happened or got worse on his watch, by blaming the country’s dissatisfaction on Vietnam and Watergate, long since faded into the national rear-view mirror. A majority of the American people weren’t buying it then, but this movie, made nearly a quarter of a century on, is still trying to turn Jimmy’s version into history. Americans were ashamed of themselves, and their hockey team made them feel better about themselves.

It’s sheer Cold War revisionism. Like Lt. John Kerry when he was leader of the Vietnam Veterans Against the War, the movie wants us to believe that “We saw America lose her sense of morality” in Vietnam. That may be what John Kerry saw — like Jimmy Carter, the man he hopes to succeed in the Oval Office. But it’s not what most Americans saw, or what happened. The pretense that it did is sheer propaganda from the same people who were wrong about everything else during the Cold War but who captured the commanding heights of the culture in the 1970s and are still there, ensconced at places like Disney and making movies like this one to tell us that we should be ashamed of our past. Maybe we should, but neither Carter nor Kerry nor Miracle even begins to make that case.

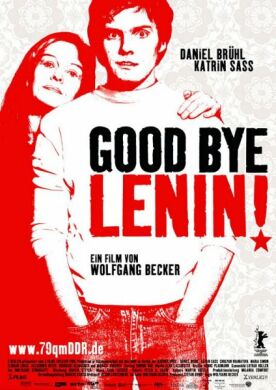

Art cuts through propaganda, making it seem irrelevant to the real lives which it almost magically — there’s the real “miracle” — creates before our eyes. And what a trick it is when an artist is able to perform his magic even in the setting of the highly political, highly propagandistic atmosphere of the Cold War. O’Connor and Guggenheim could have made Miracle without traveling by way of the Cold War at all and would have been well-advised to have gone the long way around it, rather than plunging into those treacherous waters on behalf of the blame-America school of history. But in the Movie of the Month, Good-bye, Lenin, director Wolfgang Becker and screenwriter Bernd Lichtenberg have left themselves no option. Set in East Berlin just before and after the fall of the Wall, they cannot avoid the politics of that era-defining event. Yet they manage to make the politics only incidental, as they are in the lives of most people.

Alex (Daniel Brühl) is a young TV repairman in the DDR who has been taught by his mother (Katrin Sass) to revere the achievements of their socialist motherland. Her husband, Alex’s father, fled to the West with another woman, aWest German class-enemy, years before, when Alex and his sister, Ariane (Maria Simon) were children, or so their mother tells them. A teacher, she now spends her spare time helping the neighbors to write letters of complaint to officialdom. She thinks of herself as helping in a fraternal, socialist way to make life better for everyone, though the letters are ignored.

One day in October 1989, Alex is spotted being arrested at a free-speech demonstration by his mother, who promptly suffers a near-fatal heart attack. She lies in a coma for months, well into 1990, while the Wall is being torn down, the East German state is collapsing and both the capital and the country are being re-united at the cost of considerable dislocation to those in the former Communist parts of it to the east. When she finally comes to again, Ariane has got a West German boyfriend (Alexander Beyer) and a new job working at Burger King, Alex is working for a satellite dish company and is in love with his mother’s beautiful Russian nurse, Lara (Chulpan Khamatova). Meanwhile, everything from the clothes they wore to the food they ate to the furniture they sat on in East German days has vanished. The doctor tells Alex that any sudden shock could kill his mother.

So, like the good son he is, he embarks on the mad enterprise of restoring everything in their ramshackle apartment to the way it was before, a time capsule of the now defunct DDR. Ariane is persuaded, with some difficulty, to go along with the elaborate imposture, and the West German boyfriend has to pretend to be an “Ossie.” Alex even has Denis (Florian Lukas), his pal from the satellite dish company who has ambitions to get behind the camera, make bogus news reports that he can play on television so that his mother won’t know that the world she knew before is now gone forever. At one point Alex’s vigilance is briefly relaxed and she goes outside to see obvious Westerners walking the streets. When Alex catches up with her and brings her back to the apartment, he manages to persuade her that there have been influxes of Western refugees, fed up with capitalism, coming to the East.

It is all wonderfully funny but also constantly touching, especially when Alex learns that his father hadn’t left his mother for a woman at all but for the freedom of the West, where he had hoped that she and the children would come and join him. Suddenly we realize that the split in the family is a mirror image of the split in their country, and that Alex’s desperate attempts to to preserve his mother’s Eastern paradise are as much for himself as for her. Freedom is scary. He himself realizes that his deception had “taken on a life of its own, and the made-up DDR was becoming the DDR I would have wished it to be.” Thus in a way the movie becomes an elegy for the century just past, with all its dreams of a society engineered to be perfect — dreams which, it tells us, even the most fervent socialist true believers have finally had to abandon. But it also tells us that politics is a metaphor for real life, rather than real life for politics. And that is the antithesis of Miracle’s propaganda.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.