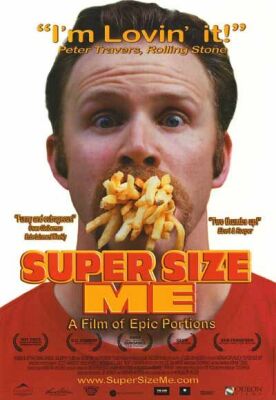

Super Size Me

A huge hit at this year’s Sundance Festival, Morgan Spurlock’s documentary Super Size Me is a well-made, humorous account of its author’s spending a month recently eating nothing but what was on the bill of fare at McDonald’s restaurants. Now, lucky man, he brings his film to market only days after the death from a heart attack of the McDonald’s chairman, Jim Cantalupe, with whom he failed to get a Michael Moore-style interview but who speaks eloquently from the grave. You will perhaps have gathered that the film does not take a favorable view of the Golden Arches. By the end of the month, Mr Spurlock had gained 25 pounds, his cholesterol and body fat had increased by 50 per cent and he was on the point of ruining his liver.

“I wouldn’t have thought you could do that with food,” says the dour, bearded Australian doctor he consulted before, during and after his binge.

Mr Spurlock is a genial, companionable autobiographer who occasionally shows rather more than most of us would like to see, including his own rectal examination, his gastric revolt against the McDonald’s diet at an early stage of the experiment and an inside look at stomach reduction surgery — not, in this case, his own. But it all helps to get his point across, and his movie has something to appeal to all kinds of progressive thinkers, as of course Sundancers mostly are. For the hard-edged politicoes there is its understated rage at the iniquity of a large corporation responsible to no one but its stockholders enriching itself by selling people unhealthy food. For the more new-agey types there is an apparent demonstration of just how unhealthy that food is compared to, say, the food prepared by Mr Spurlock’s current girlfriend, a Vegan chef. And for the conspiracy nuts there is the promise, faint as yet to be sure, of another witch-hunt to rival the legal pursuit of the tobacco companies of a few years ago.

But above all there is the gratification to be felt even by non-progressives at a new way of becoming a victim. Indeed, you could say that the whole project of the progressive movement in America since the fall of communism has been to find some way for people to count themselves among the ever-increasing pool of victims of the ever-diminishing pool of rich, white, male, heterosexual victimizers. Obviously, then, the addition of this huge new tranche of the hamburglarized, made fat by eating at McDonald’s, is great news for those among whom it would be in the poorest possible taste to point out that the victims of Mickey D have not been dragged onto the premises and force-fed Big Macs as French geese are corn.

The ever-helpful concept of addiction is always a sufficient refutation of such old-style ways of thinking, and Mr Spurlock himself claims, rather unpersuasively it seems to me, to have become addicted to McDonald’s products in the course of his month of eating them. The comedian Mitch Hedberg says that alcoholism is a disease, but it’s the only disease you can be yelled at for having. He neatly sums up our ambivalence about the concept of addiction. As an excuse for our own bad behavior it is nearly irresistible; as a reason for somebody else’s it is often infuriating. At some level we know that people do not only choose their own poisons but also actively seek for ways to deny their ability to choose them.

And yet there is one way in which Mr Spurlock does have a point. Sort of. It is not in pointing out to us the nutritional deficiencies of the somewhat limited menu served at McDonald’s restaurants. This is neither surprising nor a social problem in its own right — unless we suppose that it would be even remotely feasible politically to put the law into the business of regulating people’s diets. And if the Big Mac continues, like the cigarette, to be a legal drug, shouldn’t its users be supposed by now to know its dangers? No, the real problem is the inescapability of the popular culture. For the Golden Arches and the Happy Meals and the hideous, painted-on rictus of Ronald McDonald have all become iconic representations of the false promises of instant gratification that are repeated to us over and over again from the day that we first open our eyes to the TV screen.

I don’t mean just advertising. That’s the mistake the progressives make. The consumer society, like McDonald’s hamburgers, is not the product of a plot to enslave us by those who supply our wants. It is, rather, a natural and inevitable response to the demand we consumers constantly make for reassurance that fulfilment and happiness have a price tag on them, and that we may hope and expect to buy these things with the pictures of dead presidents. There was a time within living memory when austere political and religious creeds, aesthetic or even simple social snobbery were big enough forces in the world to tell us otherwise and so to make us at least somewhat ashamed of our appetites for sensory gratification. This is no longer true. Addicting ourselves to one form of self-indulgence or another, either consuming McDonald’s hamburgers or being self-righteous about not consuming them is the only choice we have. On what grounds are we to say that one such enjoyment is preferable to another?

Or, to put it another way, we not only like to be told but we insist on being told that we deserve a break today. And every day. It seems silly to find fault with McDonalds for giving us so much of what we demand. But maybe Mr Spurlock’s success in representing the claustrophobic sense that the world is becoming one giant red-and-yellow McDonald’s restaurant will jog one or two consciences to reflect that we are demanding the wrong things.

Discover more from James Bowman

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.